Theros

Dreams of Divinity

Theros possesses a unique metaphysical property: things believed and dreamed here eventually become real. The collective unconscious of mortal people has the literal power of creation, though the process unfolds over the course of countless centuries. Thus, the gods of Theros and their servants were believed, dreamed, and narrated into existence, materializing and becoming fully real as a result of mortal belief in their power. As stories were told, sacrifices made, and devotion given over ages, the gods formed and gained lives just as real as the mortals who dreamed them into being. Note here that the ending focus, the overarching concept that will drive the campaign forward and create a new "era" going forward is the concept of the Twilight of the Gods. Their time is ending and belief in them will dwindle making them less powerful, or those we choose to believe in and remain intertwined with will be allowed to continue on in this new era. Does that mean that the gods of Theros are less powerful or less divine than the gods of other worlds? Not at all. Once a dream or belief in Theros becomes reality, it is just as real as any other thing, and the gods have been real for a very long time. The people of Theros believe them to be divine, ageless, and all-powerful, and therefore they are. A single individual can’t do anything to make the gods less real or change the nature of a god. Threatened with the wrath of Heliod, for example, a mortal can’t simply “disbelieve” the god out of existence or turn his wrath to kindness. It’s the collective unconscious of every sapient being on Theros that shapes reality, and changes to that reality occur on the scale of ages, not moments. The concept here that I'll be playing with is that over the last few centuries disbelief and very importantly- rejection of the Gods has become more and more prevalent. People are doing so out of hate of them, believing that they should have helped them in their individual lives more, out of a desire for more free will and a move away from dependence on the Gods, and out of a moral dilemma that proved to mortals that several of the Gods can be callous and cruel and self-serving. In practical terms, then, the gods of Theros are no less real, powerful, or important to Theros than the gods of other worlds are to those worlds. Notably, though, these gods have influence only over Theros and the two planes connected to it: Nyx, the starry realm of the gods, and the Underworld, eventual home of all who die.Gods and Devotion

The central conflict in Theros is among gods, striving against each other over the devotion of mortals. Mortal devotion equates to divine power: when people fervently pray to a god, when they piously observe the god’s rites and sacrifices, and when they devoutly trust in the god’s divine might, the god becomes more powerful. Certain Gods have curried more favor with mortals, though some out of fear. More and more mortals are believing that these Gods are wrong to do this to their worshippers. There are even Gods that believe it is wrong and seek to find a better way. The competition for mortal devotion isn’t necessarily a zero-sum game. The people of Theros don’t believe in one particular god to the exclusion of others, and the most pious people pray to all the gods with equal fervor. But a deity’s goal is to increase the number of people who, when faced with peril, will call on that god for help - even to the point of arranging said peril. It’s that trust, that reliance, that faith that gives the gods their power, not merely ideas and concepts. Mortal beings—heroes and monsters alike—often become unwitting pawns in the contests of the gods. Having a powerful champion is an indication of a god’s power—and can potentially increase the god’s own power. A champion who acts as an agent of a god among other people helps increase those people’s devotion to the god. And if a hero should happen to strike down the agents of a rival god along the way, all the better.Fate and Destiny

Two closely related concepts loom large in the way mortals think about their place in the world: fate and destiny. The idea of fate is that the course of each mortal’s life is predetermined, spun out in a tapestry woven by a trio of semi-divine women, the Fates. Gods aren’t bound by the strands of fate, their lives and legends constantly changing and endlessly uncertain. In the case of most mortals, it’s thought they plod along their predetermined path from beginning to end, carrying out the tasks appointed for them until they complete their journey to the Underworld. In addition to the Twilight of the Gods, the time is ending for predetermined fate. The loom being destroyed will be an option for the characters near the end of the campaign. They'll have the choice to leave the loom intact, kill or strip the power from the Fates using a magical item, or destroy the loom and leave the Fates alive to act as small guides in the Realm of Living- unseen by mortals. This fairly bleak view of existence is undermined by the heroic ideal exemplified in myths, legends, and the lived experience of Theros’s people. Heroes, by definition, are people who defy the predetermined course of fate. They take their fate into their own hands and chart their own courses, striding boldly into the unknown, striking down supposedly invincible foes, and resisting the will of gods. Their proud defiance of fate is rewarded when they, at last, complete their mortal journeys; worthy heroes spend their afterlives in Ilysia, the fairest realm of the Underworld, where they finally rest from the struggle of their lives. In many cases, their works also live on, both in the stories of future generations and repeating in the night sky among the stars of Nyx. These heroes because of their individual acts and morality or lack thereof in the case of villains, possess such a strong "magic" of their own that it shifts the strands of fate tied to the lives withing the Loom itself. Destiny is different. The strands of destiny are spun from the hair of the ancient god Klothys, but they don’t chart a predetermined future. Destiny establishes the order of things, the hierarchy of being, the relationship between gods and mortals, the instincts and impulses that govern mortal behavior, and other aspects of the way things are. Gods and mortals alike are constrained by the threads of destiny. Mortals can do little to alter them, but more than once the arrogance and presumption of the gods have caused the strands of destiny to become tangled. The god Klothys enforces the bounds of destiny. She isn’t only the spinner of destiny’s strands but also an avenging fury, punishing the foolhardy gods who tangle them. Unlike other Gods and a singular being herself, Klothys cannot be destroyed and will remain at the end of the Twilight of the Gods. She can act as the small nudge helping to guide mortals and the remaining Gods alone or work together with the Fates to create a new world era without the Loom.Champions and Heroes

The champions of the Gods number among some of the most influential and inspirational figures in Theros. These mortals have personal relationships with the gods, potentially serving as divine agents in the world or being compelled to action by immortal schemes. Still others were born with divine gazes set upon them, whether due to their remarkable abilities or the circumstances of their birth. Through their lives, champions experience the blessings and curses of their divine relationships. Some might brandish incredible powers granted to them by the gods. Others, however, discover how fickle and vindictive the gods can be. How a champion contends with the whims of a deific patron defines what makes them a hero, whether they seek incredible ways to court immortal favor or forge a path that throws off the bonds of destiny. Regardless of the course they choose, the deeds of champions influence belief in the gods, but even more so, they fill the hearts of Theros’s people with hope and wonder. More than just for their deeds, heroes fill an important role among the inhabitants of Theros. Legendary heroes form a vast collection of well-known archetypes whose deeds create cultural touchstones and shape modern philosophies. They also embody the potential of mortals to be more than mere drops in the raging river of fate. Tales of heroes teach that greatness is achievable and that there is more to the world than what any one individual knows. The people of Theros see the truth of this in the powers of the gods and in the immortal constellations that fill the night sky. Even as the names of individual heroes might eventually fade away, their deeds live on as heroic archetypes—such as in the case of the nameless champion in the renowned epic, The Theriad. These archetypes teach and inspire, whether they’re represented in tales of journeys or creation, in sculptures rising above polis roofs, or in the temples of the gods. Throughout Theros, those who seek greatness typically begin by deciding what heroic archetype they most closely align with and letting that ideal influence their fate. The heroes illustrated throughout this introduction are examples of heroic archetypes. The General, the Protector, the Vanquisher, the Hunter, the Provider, the Warrior, the Slayer, the Philosopher, and others like them are idealized figures who appear in narrative and theatrical drama—sometimes with personal names attached, but often without. Tales describe the Slayer destroying a hydra … and a mighty cyclops, and a dragon, and a Nyxborn giant, and a lamia, and any number of other creatures. Did one Slayer do all that? No, the archetype has become the repository for legends about many different heroes, all of whom are notable primarily for slaying something. The heroes of a Theros campaign might aspire to emulate one of the great heroic archetypes, or they might strive to forge an entirely new mythic identity, to be remembered by name in tales of glory forever.Geography

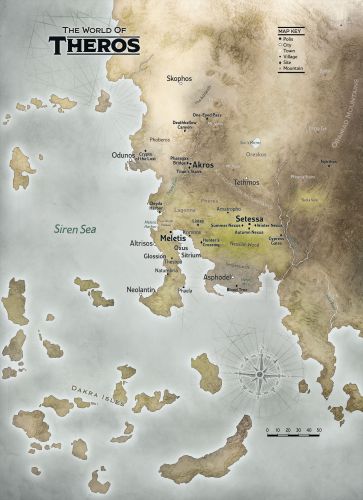

Compared to most worlds of the Material Plane, the mortal realm of Theros is small. The known world is barely two hundred miles across, with unexplored wilderness beyond. And some unknown distance beyond that is the edge of the world, where the sea flows off the disk of the world and into the starry void.

The known world of Theros consists of a long stretch of coastline forming the eastern edge of the vast Siren Sea. Eastward from the sea, the land rises up to two ridges of mountains. The lofty peaks of the second ridge form a barrier that few mortals have passed, so only rumors of a vast forest describe the land beyond.

To the north, the coastal lands become a barren region of badlands crossed by a labyrinth of arid canyons, with minotaur lands beyond. The minotaurs speak of impenetrable mountains rising amid a dark forest to the north.

The Siren Sea is studded with islands large and small. The largest cluster near the mainland, called the Dakra Isles, is poorly charted, and even those sailors who attempt to explore the isles return with contradictory information. Westward from those islands, some have successfully sailed to the edge of the world, though no one can say for certain how far it is—the journey never unfolds in a straight line. In theory, it is equally possible to sail south to the edge of the world, but those waters are stormier and more forbidding.

The heart of mortal civilization lies in and around three poleis—cities and their surrounding territories. Together the three poleis, Akros, Meletis, and Setessa, encompass most of the human population of Theros. Meletis covers the whole territory of the southwestern peninsula, Akros forms the northern frontier, and Setessa lies at the northern edge of the wild Nessian Wood.

Two bands of centaurs—the Lagonna and the Pheres—roam the hills and grasslands between the three poleis. The leonin hunt in the valley of Oreskos, nestled between the two mountain ranges. Satyrs dwell in a smaller sylvan vale northeast of the Nessian Wood. And tritons live primarily in the coastal shallows of the Siren Sea, though some manage to make comfortable homes among the humans of Meletis.

The badlands of Phoberos, northwest of Akros, are the frontier where Akroan soldiers clashed with minotaurs. Farther north is the minotaur city of Skophos, little known to humans.

The necropoleis of Asphodel and Odunos are home to the Returned—zombie-like beings who have escaped the clutches of the underworld at the cost of their identities. The lands around these cities are bleak and barren, as if the Returned brought the pall of the underworld out with them into the mortal realm.

EXPLORING THEROS

Vast and varied lands comprise the world of Theros, from the territories of the great human poleis to the dizzying peaks of the Oraniad Mountains. The line between legend and location often blurs in Theros, though. While the residents of a polis can be relatively certain their homes will remain where they left them when they venture off to work, the specific locations of legendary sites prove more nebulous. Even well-known locations are typically noted referentially, like how the city of Neolantin is often described as being along the coast, far to the southwest of Meletis. Some sites prove even more elusive. The Dakra Isles, for example, move at the whims of the gods and so prove impossible to map. As a result, Map 3.1 serves largely as a vaguely agreed-upon arrangement of locations, fuzzy borders, and general distances. While the scale and placement of sites are true by mortal standards, details might change as the gods please. As such, journeying between places is most reliably conducted by employing guides or maps specific to a single destination. If you are running a campaign in Theros, you can adjust distances between locations to suit the needs of your adventures. The distance might not be the same for two successive journeys; any trek across Theros can expand or contract to accommodate adventures and encounters as you wish.History

History and Myth

When storytellers relate the history of Theros, they always speak in the most general terms. An event of just ten years past happened “many years ago,” and the founding of Meletis in the distant past happened “many, many years ago.” In Theros, history transforms into myth more quickly than it does in other worlds, becoming generalized, vague, and moralistic. And because the gods are so deeply involved in mortal affairs, it’s often impossible to distinguish between the myths of divine activities and the scraps of historical fact in these records. The origin and generations of the gods—from the primordial titans to the modern pantheon now worshiped in Theros—are described in chapter 2. The world’s myths also fill this book, stories that still resonate in the dreams and ambitions of Theros’s people. These myths are noted in distinct sections, with the first appearing in chapter 1. Yet the largely agreed-upon history of mortal folk on Theros occurred more recently and is thought to have unfolded as follows.Age of Trax

Human history vaguely recalls an era just before the birth of modern human civilization, called the Age of Trax. This semi-mythical era, nestled several centuries back in the fog of historical memory, is marked by the rule of supernatural beings called Archons. The Archons of Trax are said to have come from unknown lands to the north and established a heavy-handed rule over the humanoids of Theros. Many peoples remember this as a time of oppressive servitude when they were forced into the armies of the tyrant Agnomakhos. The Archons dubiously suggested that their rule actually protected the weaker species—centaurs, humans, leonin, minotaurs, and satyrs—from the dangers of far more powerful beings. Giants, demons, and medusas are said to have ruled kingdoms of their own in those days, and tales tell of Agnomakhos leading his leonin soldiers to repel an invading army of giants. Dragons, krakens, and hydras are also said to have grown to even greater size in those days than they do now, annihilating whole nations and carving untold catastrophes across the land.Birth of the Poleis

The end of the Age of Trax corresponds roughly with the rise of the fourth and latest generation of gods, whose interests lie in the application of more abstract principles to the realities of mortal life. Three of these gods—Ephara, Iroas, and Karametra—played significant roles in the establishment of human civilization, in opposition to the Archons. The goddess Ephara inspired and equipped two human heroes, Kynaios and Tiro, to overthrow the Archon Agnomakhos. Divergent tales describe their history following the defeat of the tyrant. Some claim that they warred with each other for control over the region and that only their eventual death paved the way for the peace that allowed the new polis of Meletis to flourish. The truth is that they ruled Meletis peacefully together, established its legal code, and defended it for decades. After the fall of Agnomakhos and the other Archons of Trax, humans and minotaurs waged a bloody war in the highlands. The poleis of Akros and Skophos were born from that bloodshed, inspired by the martial doctrines of Iroas and Mogis rather than the legal code of Ephara. Eventually, the years of war settled into an uneasy peace with the badlands of Phoberos as a barrier separating the poleis from each other. These segregated communities of humans on one side and minotaurs on the other spread terrible rumors about each other. None of them are true and the people there are more similar than different. They wish to enjoy their lives in peace. These racial tensions do still persist among the most stubborn however on both sides and prejudice from one against another is common. Meletis, Akros, and Skophos perpetuated the stark division between civilization and nature that was inherent in the Archons’ rule. While most humans (and minotaurs) embraced that division, the god Karametra tried to teach people a new way of living in harmony with nature, leading to the founding of Setessa. The more natural loving classes and races would likely be found here.Age of Heroes

The uncounted centuries since the fall of the Archons have been marked by the exploits of great heroes, many of which are recorded in works of epic prose and poetry. Three major narratives remain widely retold and studied: The Akroan War, The Callapheia, and The Theriad. The epic tale of the Akroan War is only nominally a history of the long siege of Akros, precipitated by the queen of Olantin abandoning her husband and going to live with the Akroan king. With the war as a backdrop, a nameless poet spins tales of gods and heroes, victories and tragedies. The death of the triton queen Korinna, and the resulting birth of the Dakra Isles from Thassa’s falling tears, is a tale told incidentally, by way of comparison to the grief of the Olantian king. The tale of Phenax escaping from the Underworld is told to explain the origin of a phalanx of the Returned that comes to fight alongside the Olantian forces. And when the sphinx oracle Medomai appears and foretells the fall of Olantin, the poet tells of Medomai’s earlier prophecy of the destruction of Alephne—a tragedy that could have been averted had anyone believed the sphinx’s dire warning. The saga of Callaphe the Mariner, told in The Callapheiea, is a more coherent narrative focused on a single hero and her exploits. Known as the greatest mariner who ever lived, Callaphe was a human trickster from Meletis who sailed a ship called The Monsoon. She was the first mortal to decipher the secret patterns of the winds (provoking Thassa’s ire), and she sailed over the edge of the world and into Nyx to claim her place among the stars. The tales of her adventures are a mythic tour of the Dakra Isles and the coastlands of Theros, describing a panoply of creatures, nations, and marvelous phenomena—some of which still exist as described in its verses, though others are lost to history or myth. The Theriad is a different sort of epic, closely associated with the worship of Heliod. At a glance, it appears to be about a champion of Heliod who is never named but simply called “the Champion.” A closer read, though, reveals that the tales take place over the span of centuries, and the identity of the Champion changes from tale to tale. In fact, The Theriad is a compilation of tales describing the exploits of many different champions of the sun god. It is widely believed that some tales are actually prophecies of champions yet to come.Recent Memory

The Age of Heroes has not yet come to an end, and more epics will surely be sung and written as more heroes take their destinies into their own hands and chart their paths to the stars. The heroes of recent memory—Haktos the Unscarred, Siona and her crew on the Pyleas, Kytheon Iora, Elspeth and Daxos, Anax and Cymede, Ajani Goldmane, and countless others—are no less heroic than the protagonists of age-old epics, even if their deeds aren’t yet as widely known. Beyond individuals— a kraken attack on Meletis; the fall of the monstrous hydra Polukranos; the Nyxborn assault on Akros; Erebos’s titan felled by Heliod’s champion; the apotheosis and destruction of the mortal-turned-god Xenagos—the epic events of the recent past are already remembered and retold as mythic deeds. Many of these tales are told throughout this book, but they’re only a fraction of the myths the people of Theros share. Like white-hot bronze on the smith’s anvil, Theros is ready to be forged by the deeds of today’s heroes and ushered into the next great era of its history.Languages

Theros is not the most cosmopolitan of worlds, and a relatively small number of languages are used in its lands and sea. The citizens of the three human poleis (Meletis, Akros, and Setessa) speak their own dialects of the Common language, mutually intelligible but just different enough to identify the speaker’s native land. Leonin and minotaurs have their own languages, and tritons speak the Aquan dialect of Primordial. Centaurs and satyrs speak distinct dialects of Sylvan, and different bands of centaurs even pronounce the same words differently. Giants and cyclopes share one language. Dragons and sphinxes have distinct languages rarely spoken among mortals of Theros, and the gods themselves speak in a unique language that few beyond mortal oracles can understand.Tourism

Life in the Poleis

Human civilization in Theros is centered in three poleis: Akros, Meletis, and Setessa. These poleis exemplify the human drive to settle the land, to shape nature according to their needs, and to organize into political structures that can withstand the changing fortunes of the passing centuries. Each polis is centered in a city but includes a wide region of surrounding territory, and each one has its own distinct society and culture. To the people of Theros, “Meletis” is more or less synonymous with “Meletians”—the polis isn’t just the people who live in the city of Meletis or even those who dwell in nearby villages; it is the people who follow the Meletian way of life, wherever they might be found.Citizenship and Government

In every polis, civic responsibility and full protection are afforded only to citizens. Citizenship is limited to those whose parents were both citizens of the polis. Citizens of other poleis, and their children, aren’t permitted to participate in the government of the polis. In Akros, citizens must meet one additional requirement: they must serve in the army. The three poleis have different political structures, but each one has a council elected by popular vote of the citizenry. The Twelve, Meletis’s council of philosophers, is the democratically elected ruling body of the polis. Akros is ruled by a hereditary monarch who is advised by a council of elders elected by and from among the citizenry. Similarly, Setessa’s Ruling Council is formed by popular vote, and they govern the polis while its queen—the goddess Karametra—is absent.Trade and Currency

Trade between Akros and Meletis is constant and productive. Caravans make the two-day journey between the poleis at least once a week, carrying fine Akroan metalwork and pottery to Meletis, and Meletian fabric, stonework, and fish northward. Both poleis mint coins of copper, silver, and gold, with the equivalent value. Setessa trades with the other poleis as well, but less extensively. Its Abora Market, just inside the city gates, is open to outsiders only on certain days, and Setessan merchants prefer to barter goods rather than accept currency. Despite these restrictions, Setessan food, woodwork, and trained falcons are highly valued in the other poleis. Aside from the other human poleis, Meletis and Setessa both trade with the centaurs of the Lagonna band. The centaurs don’t work metal, so they trade woodwork, the produce of the plains, and woven blankets to the human poleis in exchange for weapons and armor.Recreation

The people of the poleis enjoy the opportunity for some recreation, as time and money allow. Gymnasia are popular gathering places, offering athletic training as well as space for philosophical discussion and friendly socializing. A resident of the city might visit a gymnasium one day to exercise, the next to view a wrestling match between celebrated competitors, and the next to hear a renowned philosopher give a lecture on ethics. Another important venue for recreation is the theater. The works of celebrated playwrights, past and present, are regularly produced by casts of professional actors. On occasion, a storyteller, accompanied by a small orchestra, draws crowds to a theater for a recitation of one of the great epics, such as The Theriad or The Callapheia. Such a performance might stretch over two or three days.Maps

-

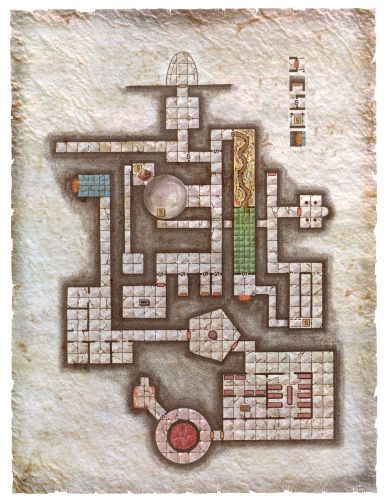

Map of Akros

-

Graveyard Temple

-

Temple at the Edge of the World

-

Jenk's Tower Ruins

-

Map of Theros

-

Mountain Shrine

Type

Continent

Included Locations

- Altrisos- Settlement of Meletis

- Asphodel

- Glossion

- Katachthon Mountains

- Krimnos

- Listes

- Meletis Metal Trades

- Natumbria

- Neolantin

- Nessian Wood

- Nexuses of the Seasons- Spring Nexus

- Nexuses of the Seasons- Summer Nexus

- Odunos

- Oreskos

- Oxus

- Phaela

- Phoberos

- Pyrgnos Tower

- Sitrium

- Skophos

- The Brass Basilisk- Middle Class Tavern

- The Dekatia of Meletis

- The Different Sign- Low End Tavern

- The Full Pot, Grocery & Supplies

- The Intelligent Pen Booksellers

- The Mystic Mythic- Magic Shop of Meletis

- The Observatory of Meletis

- The Siren Sea

- The Third Tower- Upper-Class Tavern

- Thesteia

Included Organizations

Characters in Location

Related Reports (Primary)

Related Reports (Secondary)