Lordslands of Milos

The name Milos (and thus the Milosian Peninsula) came from the Orckid Conquest, and stuck after the Great Collapse. It is from the Brevessarian "Maiad," meaning "south," and "Os," meaning "land/people."

The Kingsrift

Yfri Fields

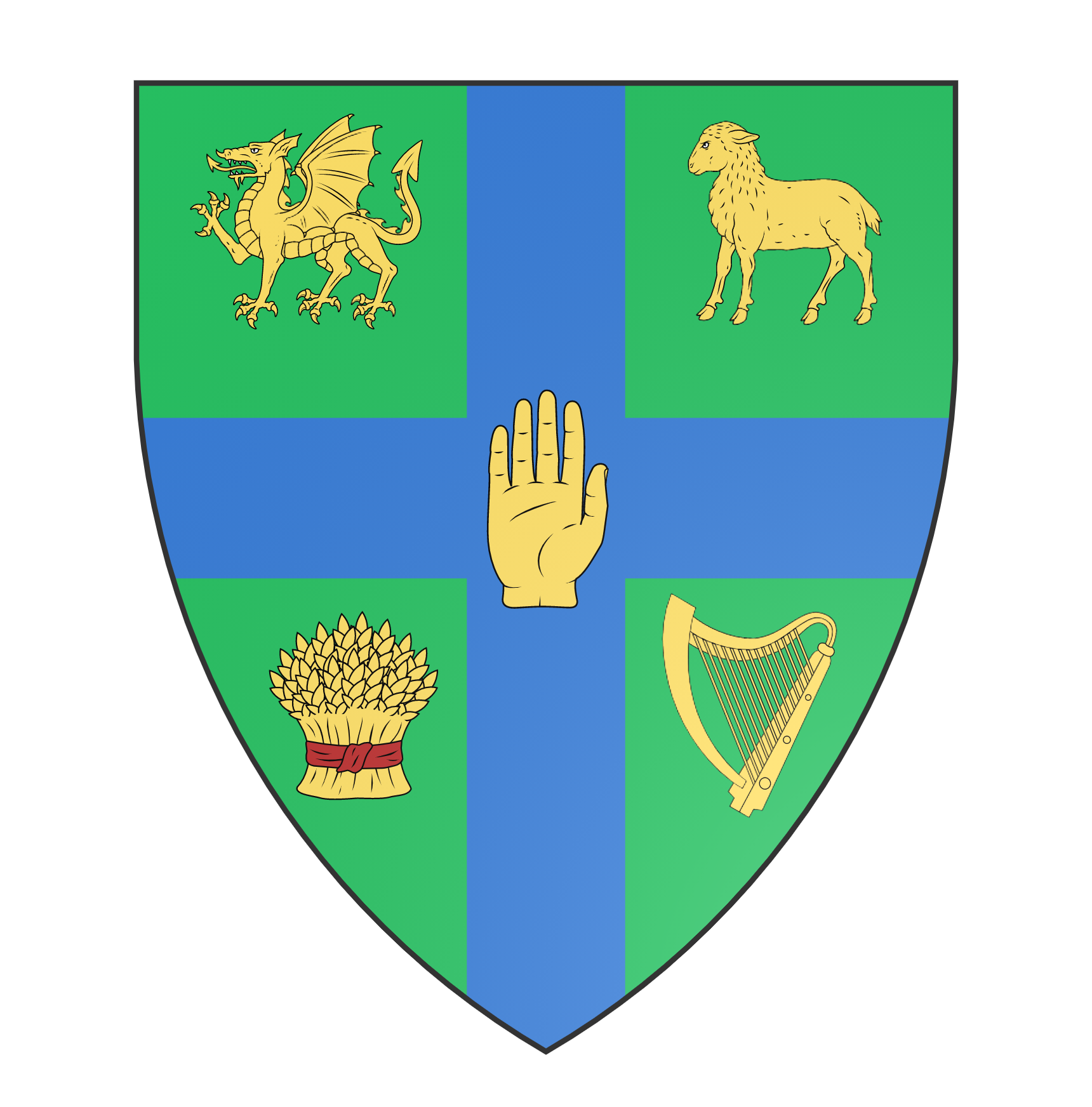

Bastis by JD Medaeris with Armoria

The Hostlands

Ethel

Lorden

Revellia

Structure

Having been a collection of petty kingdoms for thousands of years, the Lordslands of Milos is now a "Free Land," owing allegiance to no holy king, where anyone may own property and ascend to lordship. In practice, of course, some lords are greater than others, and the petty kings of ages past have been replaced with great lords.

History

Often referred to merely as “The Peninsula,” Milos is largely an insignificant and forgotten part of the continent of Kynaj. Many of its customs were imported from Monos, with none of the worldliness that Monos’ geographical position might portend. Indeed, most things that happen in Monos happen in Milos more simply, more numbly, and to lesser effect. In many ways, the peninsula is considered an age behind most other nations. Even its sex divisions, itself a probable import from the Mornal Invasion via Monos, is a sad reflection of the nation’s ignorance of its own history, an ignorance only perpetuated by that same division.

More than anything, Milosians are unknowing: of who there are, where they live, or what they have been. Their distrust of spelling, engendered by the conquest of the Old Orckid Empire then enflamed by the New, ultimately came to the Burning of the Great Spellery at what is now Cantef. With this was lost all history of the people who came to be known as the Milosians. All we have left are legends passed down, a smattering of carved glyphs on rocks, and the legacies of mightier nations that sought to control the Peninsula.

As such, any history from before the Milosian Age of the King, including much of the Orckid Age, must be treated entirely as speculation.

Despite its relative isolation, Milos has been heavily influenced by four, arguably five, outside sources. Kingsfield and the Host Lands, being farthest north, are most heavily influenced by Monos, though of course Host-Keeping is found throughout the Peninsula. Bastis and the Yfri Fields, somewhat insulated from Monos by their northern neighbors, retain great influence from their brief history under the Late Orckid Empire. Lorden, of course, remains hugely influenced by the Khabarese Crusade. Ethel and Revellia, being farthest from all these foreign influences, retain more of the original cultures of the Milosian people (as, presumably does the Isle of Qosx), though many have noted that the mercantile nation of Eysland is having a notable impact on Ethel’s culture. Finally, the Viisianari have long faded from the nation, but its effects can still be felt throughout.

Because of these many conflicting influences, the Peninsula has been said to have four histories: Satari, Monosi, Orckid, and Aernigh. Since the Aernigh were presumably the first inhabitants of Milos, perspectives believed to hail from them shall be given preference whenever possible.

The Peninsula is one of those rare places that intelligent life evolved separately from the Cradle of Yaalk (where all human beings originally hale from). The Aernigh are called many things: The Folk from Before, the Children of Pride, the Fallen Folk. They were smaller than modern peoples (who themselves were smaller then), had sharp fangs and claws, and are believed to have had pointed ears (though this may be merely the product of magicians and crude drawings from many generations later). They were divided amongst themselves into six clans, which often warred against each other: the Revali of the Rivers (often called sprites), the Glastins of the forest (often called fauns, and who wore pelts and antlers), the Bodoxi of the bogs (sometimes called boggarts), the Darraks of the hills and caves (sometimes called red caps, for they drank and bathed in blood), the Sembraxi of the plains (called giants, for they alone were unusually tall), and the Foulaxi of the southern frozen woods (called werewolves, for they wore wolf pelts and hunted at night). Ancient bones suggest these peoples fought whenever they encountered each other, but largely kept to their own domains.

Naturally, myths run rampant even today that these peoples still exist somewhere. Go deep enough into the woods, and you shall find a Glastin or a Foulax hunting you. Get lost in the bogs, and a Bodox will catch and drown you. Lone miners will be grabbed by a Darrak and dragged into the dark. And many is the man who thought he had stumbled upon a mossy-haired maiden bathing in a stream at night, to his briefly-lived regret. There are no such myths for the giants, though. They lived on the plains, in the open, and were the first to fall before the coming New Folk from the north.

Like much of eastern Kynaj, the Milosians were originally Monosi, one of the Three Great Peoples of the continent. It is believed they split from the “Pure” Monosi sometime in the Middle Wild Age, after the emergence of the first King of Kings. The King of Kings, if he did exist, was a powerful Monosi warlord who united all the disparate Monosi tribes under his single rule, which he claimed to be divine in origin. Most believe it was a rejection of this rule that led to three groups of people migrating away from the Sea of Trials: northeast to become the Brevessarians (later the Vainans), east to become the Samayans, and south to become the Milosians.

Unlike the Rivers of Vaina or the Wetlands of Samaya, which were uninhabited before the settlers arrived, the first Milosians had to contend with the Aernigh. It is believed first contact between these two peoples took place on the open fields, between early Milosians and the Sembraxi: the giants. Bones suggest some conflicts took place between these two groups, yet although ancient weapons of bone and rock can be found amongst human remains, the giants appear unarmed. Often standing eight feet tall, it may be the giants were accustomed to treading the fields unchallenged and felt no need to research warcraft. It has also been postulated, however, that the Sembraxi were a peaceful people, and that their extinction came merely from the fears of a smaller people, or even from nothing more than the desire to control the land. The Sembraxi were almost certainly shepherds, a trade the early Milosians presumably picked up after the threat of these big people was neutralized.

While we may, perhaps, excuse the extinction of the Sembraxi as necessary for the Milosians’ continued existence on the Peninsula, their wars against the other Aernigh are less clearly motivated. Humans need wood for fires and to build homes, yet the Glastins and the Foulaxi were believed to live deep within the hearts of the forests, the Foulaxi only venturing outside at night. Bodoxi and Darraks were even more inaccessible without strong motivation, and the Revali were even fewer in number than the Sembraxi. Yet still, the Milosians found a need to engage them all in war. Perhaps random villagers had wandered into their domains and suffered the consequences, once too often. Perhaps early folk caught glimpses of figures in the shadows, and out of terror, gathered their superior numbers and marched into the nooks and crannies of the Peninsula. Or, perhaps these Aernigh, many seemingly accustomed to warring against each other, turned their violent customs on their new neighbors and suffered the consequences. Though the weaponry of these two peoples were similar, stone and bone, the Milosians far outnumbered the Ancient Folk, and there is no evidence of their disparate people banding together in hopes of countering those numbers. Some suggest that the Aernigh survive today, hiding away in their holes, their deep swamps, and the darkest parts of the wood. Yet if even our ancient ancestors could root these people out of their homes and unto their ruin, what chance would any such creatures have today?

Regardless, long before the end of the Wild Age, the Peninsula was dominated by humanity. It is believed that the cold climate and wet conditions contributed to the relatively pale complexion of these peoples, though some suggest it is the absence of a soul that makes them so ghast, indicating both their slaughter of the Aernigh and the cruelty of the Mornals who came later, themselves even ghastlier in pallor. In truth, there is not a nation on this earth, from the frigid climbs of Eysland in the east all the way to the Great Savannah of Batalia to the west, that was not built on the bones of people who came before.

Like most Kynaji people, the Peninsulans spent the latter Wild Age split into various clans, usually extended families. There are some traces suggesting mild levels of migration (north in the winter, south in the summer), but by the end of the Wild Age they appear to have settled into tribal communities. The Peninsulans were among the last civilizations to discover agriculture, and in many ways this signaled the end of the Wild Age for them. However, the Imperial Age (or as they called it, the Orckid Age) would not begin for Milos until 1550 IA. This period between the end of the Wild Age and the Orckid Empire’s Conquest of the region, would come to be known as the Age of Gods or the Gods Age. More recently, it has been called the Age of Devils.

The beliefs of the earliest Peninsulans are unknown, but if we are correct in assuming they came south to escape the early Kings of Kings, it stands to reason that like the Monosi, they were primitive Host-Keepers. Unfortunately, even early Host-Keeping is merely speculation. It’s entirely possible that the myth of the King of Kings was a separate belief that became married to Host-Keeping much later on in the development of the two nations. Ultimately, we will never know just want the earliest Peninsulans believed. It is likely they were followers of an animist faith, however, because there are strong indications that the Age of Gods was a time when they attached themselves to the gods of the Aernigh they had destroyed.

The Burning Ram, in addition to being the spirit that guided all sheep, was also the creature that guided the sun across the sky, and it is believed that Peninsulans would sacrifice sheep to the Burning Ram in the winter to ensure Summer’s return; some suggest they performed such sacrifices every night to ensure the sunrise, and that this may well be where the custom of eating burnt flesh came from in the Peninsula. The Burning Ram was the god of the giants, and therefore one of the earliest beings worshipped by the Milosians.

The Revali worshipped sky-wyrms, whom they believed brought the rain, and so did humans come to do. Eskri the Cow Queen was not only the spirit of all cattle, but also the source of fertility and protector of children (and one of the surest proofs that Milosian gender roles may have existed before the Mornal Invasion, as this early faith featured few women, those women being associated almost exclusively with childbearing, marriage, or love). The Darraks worshiped Bethril, the Father of Swine who was also believed to have created humans. The Darraks, it should be noted, were cannibals who ate members of other clans (and later, humans), eating pigs only when they could not eat people. The Peninsulans’ worship of Bethril might well suggest that they too were no strangers to the taste of human flesh, and its reported similarity to pork.

There were gods for rivers, trees, grass, fish, and life and death, and most were the subjects of worship and appeal in the hopes of gaining their favor. The one god who was avoided rather than worshipped was Nabas, the Wolf of Night. A cruel predator, powerful shapeshifter, and heartless trickster, Nabas was alternately believed to chase the sun away, to hold the moon in his jaws, or to be the entire night sky, blotting out all light save the Cow Queen’s moon and the Children of Light who speckled his belly. Regardless, long after the nocturnal Foulaxi had ceased to terrorize them by night, the Peninsulans continued to avoid nighttime activities, and many are their legends and myths of fools being drawn outside at night and suffering the consequences. Some of these myths involve mortal wolves pretending to be women or children in trouble or even great lords sounding calls to war; others involve beautiful women bathing in a nearby river that turn to sharp-clawed monsters upon approach (no doubt a callback to the Revali), but the most compelling myths involved Nabas himself, wherein he would try elaborate tricks or riddles to convince someone to come out into the night. In some of the tales, an admirable mortal would prove more cunning and manage to outwit the Wolf of Night, but far more often the victims would finally submit and walk out to their doom. These myths contained different lessons depending on the nature of Nabas’ trickery, but their central message was always the same: don’t go out at night.

The pervasiveness of this fear may well have been justified. While bones have been found of early Peninsulans who seem to have wandered into the woods at night (or become lost there) and more than one person’s remains have been found in the rivers, there are even remains found in open areas, far from battlegrounds and villages. These strange deaths lead many to suppose of that the ancient Peninsula had a population of murderous wanderers who might attack strangers at night. This was before coinage was introduced to Milos, however, so exactly what wealth these highwaymen might have been extracting, remains unclear.

Which is not to say that Gods Age Peninsulans did not have plenty of other ways to die. Being divided into so many clans meant that warfare was frequent. Though there is some evidence that battles were fought over who worshipped which of the many deities more prominently, it seems likely that most conflicts were over who could control which land, and whose forefathers had taken said land and must now suffer for that. As it was ever.

Regardless, this era of Milosian history came to a close in the middle of the 16th Century IA, when at last the Orckid Empire descended upon them.

When the mighty Viisianari military sent their spell-soldiers, called adepts, into the Peninsula it must have resembled sending behemoths against Yenai midge mice. The Milosians still had not discovered metallurgy, and they resisted invasion with their weapons of bone and wood and rock. A single prodigy (their mid-level commanders) or virtuoso (the highest non-royal rank in Orckid) could well have wiped out an entire Milosian army, and it appears thousands upon thousands of warriors died resisting. Perhaps the one positive of this slaughter is that the ease with which Orckid conquered the Peninsula made it simple to avoid killing women and children. Based on Orckid records, the entire Peninsula fell under Imperial control within a single year: 1550 IA, a mere three centuries before the mightiest empire that every existed would fall to the Mornal invasion.

Despite the shame of defeat, it is hard to argue that Orckid’s occupation of Milos was not extraordinarily beneficial. Few warriors surrendered, so slavery never took solid hold in the Peninsula, being reserved only for insurrectionists, rebels, and certain thieves. The Peninsulans were forced to pay taxes to an Orckid governor (instead of whatever chieftain ruled them before), but for the first time in history they had valuables that could be taxed. Mining, smithing, medicines, arithmetic, astronomy, roads, advanced architecture, and (for better or worse) spelling finally began to flourish. Even the name Milos was a product of the Viisianari. If the peoples of the Peninsula had any name for it beforehand, that wisdom is lost, perhaps burned in the Great Spellery.

Despite these many palpable benefits, Orckid records indicate that small-scale resistance was common, with individual villages rebelling at a rate of about one a year. Governate outposts, called auditoriums, were erected at the edge of most towns in response, where the local Orckid representative would hear grievances and dispense justice. These governors had their hands full already, promoting irrigation and agriculture to make the Milosians more self-sufficient, updating buildings and even educating the more gifted locals on spelling. While spelling was theoretically available to anyone, governors would (at their discretion) offer to take promising young girls under their wing to be trained in spelling and sometimes even magic. Many Milosian former-rulers objected to this, possibly because it was seen as a way of turning their children against them, but also quite possibly because it represented a form of women gaining power over men. Either way, while rebellions never died out completely, over the centuries Peninsulan views on the Empire evolved, and many chieftains began to seek out ways to earn citizenship.

Earning Orckid citizenship meant a village would receive greater funding, all buildings (even peasants’ homes) could be updated to the most modern styles, and spelleries (which taught spelling and magic) and even wizardries (which also taught arithmetic, astronomy, biology, geography, and of course the Viisianari language) might be constructed. Neighboring chieftains began to vie against each other to impress the local governates. These competitions were usually peaceful, if still ruinous: chieftains would spend all their wealth feting and flattering governors, often bankrupting their villages in the process, of course ignoring the small contingents who wished to minimize Orckid presence, which would frequently lead to more rebellions.

The Empire demarcated Milos into eight provinces, most of which survive today in some form: Rathael (now Revellia), Erevrael (now Lorden), Austmael (now Ethel), Yvrael (now the Yfri Fields), Basrael (now Bastis), as well as Cenedrael, Divruel, and finally Firrael, which comprised most of what is now Kingsfield. Each of these eight provinces was overseen by a Governor, who had a Prefect for each settlement, with the whole of Milos being ruled by an Overlord (sometimes called a Virtuoso, since most early overlords were virtuosos).

As far as can be told, the greatest event in Milos during this occupation was the building of the Great Spellery, in what is now Cantef. Spelleries were common in other Imperial holdings, and indeed records suggest that some Milosian settlements now had them, so it is not entirely clear what made this Spellery great. Whether it was constructed with special plans, or whether it became significant over time, none can say, but over the course of the Empire’s reign, the Great Spellery became the chief repository for all writings, as well as a source for magical instruments, and most importantly, the primary location in the Peninsula for training in the magical arts and its peripheral disciplines.

Smatterings of quotes suggest there may have been plans for Milos, to transform it into another magical center like the Kingdom of Vaina and the great Orckid cities of Ol Illothrend, Ajman, and Chuereb. It may be that the men (or even some of the women) of Milos objected to the gendered power dynamic this might introduce, or it may be that the Mornal Invasion and subsequent Great Collapse of the Orckid Empire resulted in great upheavals. Tragically, this is just one of the thousands of things we will never know about this point in history and especially about Milos, for some time during this era, almost certainly in the early Royal Age (after the Great Collapse), the Great Spellery was burned to the ground. The cause is still unknown, and a few even suggest it was a mere accident. Much of what is Cantef is also believed to have been attacked and destroyed at this time, so theories of accident are few and unpopular. Many students of history weep over this tale, for though Milos was never a center of culture or learning, many sorrow for what it might have been.

Some consider this the beginning of the Dark Age, a time in Milosian history when virtually nothing is known. This is not an official age, however, and indeed many hasten to point out that very little is known about Milosian history at any time before the Age of Kings.

Just as Milos entered the Imperial Age quite late, so its effects lingered long after the Age had ended. Ruins and remains suggest that many horrific battles were fought in the Peninsula after the Mornals took over: whether these were rebellions, religious purges, territorial disputes, personal grudges, or any combination thereof, will likely never be known.

What is known is that the Peninsula, backwater though it was, would prove to be a place of refuge for other peoples. Many of those who fled the Empire both during Viisinari rule and especially during Mornal rule and even after the Collapse, would find themselves in Milos. Their cultures rarely meshed, however, and whether due to intolerance or assimilation, most such immigrants became thoroughly Milosian within a few generations, providing nothing more than some superficially aesthetic diversity to the famously ghast Peninsulans.

It is impossible to find a specific date at which kings reemerged in Milos. It may well be they never left, that they simply submitted to the Empire until sometime after the Collapse, at which point rebellions became more effective and kings reasserted their power. It may be that some great rebellion swept Imperial power structure from the land. Because of this confusion, most date the start of the Age of Kings (essentially when the Royal Age began to have an effect in the Peninsula) as 506 RA, the year of Cenedras’ Southern Conquest.

Though still muddled by time, it seems plausible that Milos was a nation of Host-Keepers at the time of Cenedras’ Conquest. It may be that the Milosians were already sympathetic to the notion of a King of Kings, which could explain the relative ease with which Cenedras took the Peninsula. Of course, it is also likely that Cenedras prevailed due to superior numbers, arms, and strategy, and that the concept of the King of Kings and the Host of Hosts, something modern Milosian culture is built on, did not exist before the Middle Royal Age. As always, we may never know.

Once conquest was assured, however, most Kings of Kings had very little to do with the Peninsula. They extracted taxation through hostermen and sometimes hostesses, and Milosians appear to have viewed the King of Kings as a divine figure, rather than a political ruler; there are even records of skeptics being hanged or burned for doubting the King of Kings’ existence, despite his being a flesh-and-blood person.

It was not until the Khabarese Crusade that more regulated recordkeeping finally became a staple of Milosian life, but through references and word-of-mouth stories eventually being written down, we are able to gain some insight into the Peninsula during Cenedras’ Conquest, and in the time between this conquest and the Khabarese Crusade.

Cenedras the Fourth was a Monosi King of Kings who sought to glorify himself through conquest. Unfortunately, he began his conquest westward into Zalja, where invasion without a writ of war was considered barbarically dishonorable. Consequently, in spite of his many successful battles and occasionally wise rule, Cenedras the Fourth is forever known as Cenedras the Liar.

After taking some of eastern Zalja, Cenedras next looked south to the Peninsula. It is believed the last King of Firrael died around this time, but whether he was slain by Mornal governors or by Cenedras’ invasion, or even by a local uprising, is unknown. Regardless, the petty kingdom of Firrael was dissolved and became what we know nowadays as Kingsfield. Cenedras is generally credited with slaying the last King of Cenedrael, dissolving that northeastern region and combining it with Kingsfield (this area would later become a significant part of the Yrif Fields, before being converted into the Host Lands).

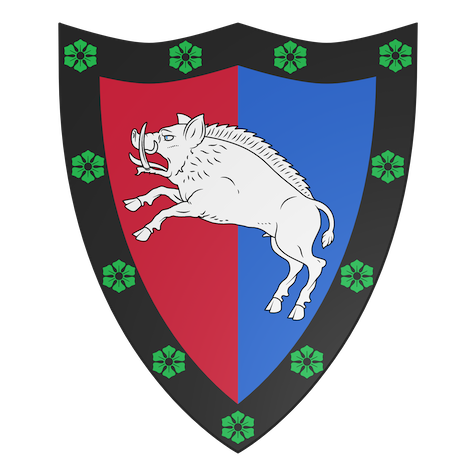

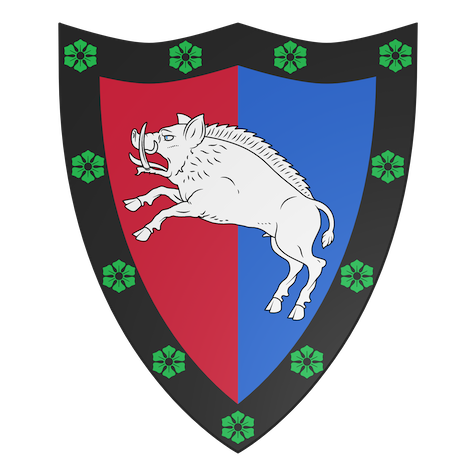

Bastis was then ruled by King Scorich the Grey, a grim and fearsome warlord that many called a sorcerer. This was not the first time that “low magic,” some especially depraved form of magic supposedly practiced by men, was reported in Monosi records. Several of their own Kings of Kings would prove to hold an unhealthy interest in magic over the years. Fortunately, so-called “low magic” has never been reported to have manifested in any real way and is largely dismissed as rumor. Regardless, King Scorich’s alleged sorcery did not serve his army, composed principally of foot with some slings. There were no archers, and the only cavalry were members of the royal family. Their most unique military force were great scores of trained dogs, called wolflings or werewolves, that had supposedly been the terror of all Scorich’s enemies, before Cenedras. It is unclear if Scorich was a Milosian king or a Mornal governor that had crowned himself; regardless, his line was wiped out and replaced by the line of Barbis, who knelt and swore fealty to the King of Kings.

Yvruel to the east would prove to be the mightiest of Cendras’ adversaries, so he instead continued south to what is now Lorden, and King Harrold the Bull. Harrold is now a legendary figure of defiance in Lorden, and so is widely assumed to have been Milosian; many legends suggest he ejected Mornal governors even before the Collapse, though this is widely dismissed by spellers. Though his army was stronger and more regimented than Scorich the Grey’s, he still fell before Cenedras.

The Bull put up a good fight, however, and while he was fighting the remaining cantons were conferring. Spellers were still a rarity in Milos, but the mightiest of men could retain the services of great spellers, arithmeticians, and magicians. The greatest of such women could do all three, sometimes more. These Milosian-virtuosos were called Wizards, and the wisest kings sought to keep them under their service. The wizards of Divruel, Rathuel, and Austmael, with their kings’ consent, coordinated a joint defense against Cenedras’ army. They met the Monosi forces at the Pass of Pride (now the Darkling Pinch), a field in modern Lorden that had once lay near the border of Divruel and Erevruel (Lorden). With the Bogs of Buco to the west (modern day Spellmire) and the Orysi Hills to the east, the Three Armies were able to draw Cenedras into an enclosure. The King of Kings had grown overconfident and charged headlong into the trap.

Divruel was reported to hold great troops of mounted warriors, with some legends claiming they rode great warthogs. Rathuel (Revellia) had scores of trained pikes and a few career warchiefs called Mox Men, who rode horses and wore steel armor (either stolen from Mornal warriors or forged in Mornal smiths some legends say they rode river wyrms lent them by the Ancient Revali. Austmael lent relatively few troops, but the ones they provided were pivotal: great bowmen, called Dydraxi, trained to fire enormous bows of Dydra wood, launching foot-long arrows with rusty iron tips farther than any other bow in the Peninsula.

This would prove to be King Cenedras IV’s one loss during his conquest. He was made to retreat to a town called Faringwood (long since lost) and regroup. The kings celebrated their victory and, after a brief squabble over some of the spoils, returned to their respective seats. The Wizard of Rathuel warned all that this King of Kings would return, but none listened. King Markius of Divruel went so far as to try a counterstrike to push Cenedras out of Erevruel (Lorden), intending to claim the land for himself.

The results were disastrous. King Markius led his men through the Faring Forest (now largely dispersed and hewn down) in hopes of approaching Cenedras unseen. The Forest was deep and dark back then, however, and many of his men were taken in the night, presumably by wolves. Wolves are rare in the area today, leading many to suggest they were in fact taken by Foulaxi. Of course, Foulaxi, when (and if) they lived, were native to the frozen woods of the southern taiga. If any of the Aernigh still lived in the region, it would be the Glastins (the so-called fauns), so this muddled story of “werewolves” would seem to support the notion that it was indeed wolves that so harried King Markius’ forces. Either way, the troops that emerged north of the Faring Wood were greatly diminished, disheartened, and in poor condition. They were also immediately seen by Cenedras’ forces in Faringwood, who made short work of them and hastened south (around the forest) into Divruel proper. Divruel was conquered and given over to one of Cenedras’ principal bannermen, Lord Ormo Pelendor, whose line would rule over Divruel until its end.

Upon learning of this, Rathuel and Austmael tried another alliance, this time hoping to join with mighty Yvruel. Yvruel had a history of aiming too high in the face of conquerors, however, and would prove true to form here. Rather than unite with his fellow Milosians, King Torik the Third sought to ally with Cenedras the Fourth against his southern neighbors, seeking to split the spoils with the King of Kings. As ever, Yvruel’s faith in its own greatness would go unshared, and Cenedras instead made offers to Rathuel and Austmael: swear fealty to the King of Kings and offer your swords against Yvruel, and retain your seats and titles. Refuse, and die. Two troops of five spellers each, escorted by fifty-five hostermen each, delivered these directives.

King Bartimus of Rathuel received the messengers with great respect and ceremony, but politely refused the directive. He claimed that, although the varied nations of Milos had vied against one another in many conflicts, he would never unite with a foreign power against his own cousins. He further expounded that many a peace had been made over the centuries, sealed with marriages between the tribes and later kingdoms, so to assent to Cenedras’ command would be to assent to the slaying of his own kin by a stranger’s order, and this he could not abide. When pressed to consider his piety, that Cenedras was of the unbroken line divine, Bartimus (supposedly) made one of the most revelatory statements of this era: “The King of Kings commands our laws, when one chief defies another. But in our hearts, we still are ruled by those Ancient Gods that, dear and lament, have passed from this world.” Entire codices have been spelt on what this could mean. Did the old Revellians worship the same gods as the Aernigh? Did they worship the Aernigh themselves? Which ones? Did this declaration of faith extend only to Bartimus’ family? All of Revellia? The entire Peninsula? Sadly, nothing more is recorded or postulated on Milosian beliefs from this era.

King Erick of Austmael would prove more reasonable. He agreed to swear fealty to Cenedras, and once confirmed in his titles, agreed further to help the King of Kings wipe out Rathuel to the south. As a reward for his enthusiastic loyalty, he requested one of the King of Kings’ most promising apprentice smiths, tanners, and tailors, each in service to Austmael for ten years. Cenedras granted this without hesitation.

Many legends survive of this, the Destruction of Rathuel. Some stories have King Bartimus offering poetic defiance on the field of battle. Some have him dying on King Erick’s sword, whilst others suggest Erick was too cowardly to go forth himself. Still other stories pit Bartimus and Cenedras himself against one another, and a few rash fooleries even say the King of Kings died and that Bartimus lived on. Other stories say his brothers or sons fled deep into the taiga of western Rathuel to dwell amongst the ghosts and Revali and Foulaxi. Although little enough is known of this era, we know that Rathuel was dissolved and its lands granted to Ormo Pelendor, Lord of Divruel and Cenedras’ trusted friend.

This left only one obstacle to Cenedras’ total domination of the Peninsula: Yvruel. A region prone to boom-and-bust, Yvruel was presently very much in a boom: their lords and especially their kings had worked with their Mornal oppressors more fervently even than they had their Viisianari ones, and had drawn the benefits of such. They controlled more horses and better steel than the rest of the Peninsula, and its citadel (called the Redoubt) was unmatched on the eastern edge of the continent (except of course by the Fort in Vaina). Yet for all this, Yvruel lacked a wizard. Cenedras and his new vassals were able to coordinate an attack from three fronts: north-and-west from the two eastern rivers now called the Breaches, northeast from the Pass of Pride (Darkling Pinch), and south-and-east from Fonte. Yvruel’s outlying towns fell at once, and no coordinated defense could arrive from the far east. The capital of Withested was surrounded.

Rather than surrender or starve, King Jannus of Yvruel sent out his first son Joron to cast his gauntlet at Cendras’ feet, demanding that the matter be resolved in Hollymock: ritualized dueling. If only King Jannus knew who he was dealing with, he might instead have simply surrendered.

In Monos to the north, duels were simpler: two men faced one another and fought to the death. Hollymock was fought with short sword and shield (or ax and shield, in some instances). Three shields were granted to each combatant, and whoever broke three shields first was the victor. This all was explained to Cenedras, yet when battle began he immediately hamstrung King Jannus, then stabbed his throat. He would later claim he had misunderstood the rules. Jannus’ son Joron offered defiance and said they would repel any attack with their walls. Cenedras slew him as soon as he turned to reenter Withested. Jannus’ second son, eleven-year-old Marten, would later come out from Withested with his mother Annadiel to lay his sword at Cenedras’ feet. Darker myths claim the Liar was about to murder the boy too, but became taken with his mother Annadiel and spared him for her sake, taking her to bed that night and for a fortnight after. Annadiel’s true fate, and that of Marten and everyone else, of course, is muddied as everything from this era.

Thiswise the so-called hundred-and-twenty-third King of Kings, Cenedras the Fourth, the Liar, took the Peninsula of Milos under his rule. It was said he would progress around the peninsula for another two years before finally returning home and mounting an unsuccessful sally into Samaya (more likely he never made it in, given that mysterious nation’s reputation). Others suggest the Monosi, being far more accustomed to warmer climes, could not wait to get out of Milos, and some legends say the King of Kings spat upon the fields outside Withested before immediately riding north, never to return.

The next century-and-a-half is often called the Lost Age. Recordkeeping was improving thanks to the growing advent of Wizards. Women of powerful education could be found serving all kings, most lords, and even the odd chieftain, roaming amongst lesser villages. A woman who “knew her place” was allowed to excel in the elevated arts, and the fear of women’s literacy that had climaxed in the burning of the Great Spellery at Cantef seemed to be receding.

Yet for all this, the men who ruled the lands remained skeptical and fearful of magic and spelling. They would not share their knowledge with others, and a wizard who sought to spread what she knew, or even to exercise it for anything beyond the king’s service might find herself hanged or even burned. As such, historical records rarely outlived the people they described. Heirs often ordered the burning of old spells and records, and conquering lords were twice as likely to command such burnings, often burning the wizard that made the records as well. As such, while our knowledge of this time is far better than any previous age, much of what we claim to know remains guesswork.

Divruel was the greatest power in the Peninsula at the outset of the Lost Age. Covering most of what is now Lorden and Revellia, it was ruled by the Pelendors, favorites of the King of Kings. They consequently enjoyed lenient taxes, salt and ores, vast amount of varied lumber, cattle, swine, and more horses than any region outside of Yvruel.

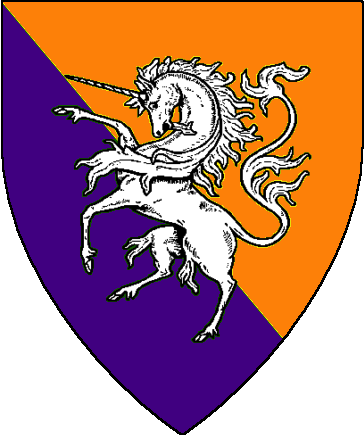

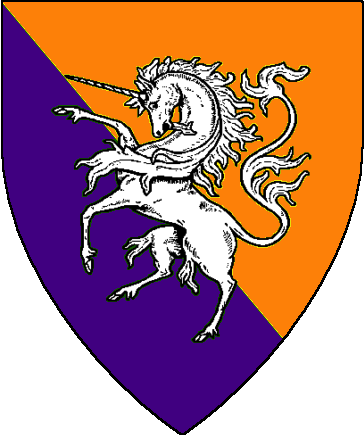

The House of Pelendor is widely credited with spreading the heraldic system through Milos. Their standard, a golden stork upon an indigo and white field, would become one of the most hated images in all the land, and other kings are believed to have created their own standards in defiance of it.

Ormo Pelendor reportedly grew rich off the largesse granted him by the King of Kings, but he also laid the groundwork for the destruction of his house when, nearing his death, he bequeathed his great kingdom jointly to his two sons, Orido and Eugen.

Orido inherited the northern half, and therefore most of the wealth, while Eugen inherited the southern half, “a frozen waste” as he called it. This would lead to several foolish and destructive border skirmishes between the two brothers, skirmishes that would not go unnoticed by Austmael to the east nor Basrael in the north; nor, for that matter, by Eugen Pelendor’s own citizens.

As his sense of being slighted grew, Eugen took it upon himself to officiate the gathering of taxes for the King of Kings. He sent his “king’s men,” armed troops imitating hostermen, ahead of the actual tax collectors to gather coinage. They would then show Eugen’s seal to the real hostermen when they arrived, and take over the transfer of the wealth north into Monos. This resulted in some mild confrontations the first few years, but Monos still received its taxes, and the hostermen were free for nobler pursuits. In the fourth year of this, Eugen began skimming some of the taxes before sending it north. These percentages grew steadily during his reign over South Divruel, which he would rename Eurael.

Orido, as one might expect, sent complaints of this practice to the King of Kings, who failed to act. Eugen was skimming enough to make a small fortune, yet not enough that the King of Kings saw any significant loss in his own wealth. Orido took it upon himself stop these evils. In 515 RA, he marched troops into Eurael to Eastmow, the then-capital, only to find himself thoroughly outmatched. Eugen had used his ill-gotten wealth to restore Aerwoth port, and hired mercenaries from Eysland. Called Eyschers, these men were known for their diverse and colorful outfits, as well as their merciless brutality in combat. Eugen overwhelmed Orido’s forces, took his brother captive, and marched into North Divruel. He had offered clemency to any soldier that surrendered, but as he did not speak the Eysch tongue, he failed to communicate this directive effectively to his soldiers.

Eugen seized North Divruel and united the two kingdoms under the name of Eurael. Yet before news could reach the King of Kings, another counterattack took place.

Orido and Eugen inherited their thrones with many advantages, but they did not have wizards. In the far south of the Peninsula, a war chief named Kedan had secured the service of a Wizard named Roshin. Together, they coordinated a counterstrike with the new king of Erevrael, Egon Barbis. As Erevrael’s armies attacked and drew Eugen’s forces north, a great rebellion emerged from Revelback, led by Kedan and the Wizard Roshin. As ever, there are legends of the Aernigh fighting with the rebels, emerging from their rivers and their deep forests to eject the foreign army. Of course, this tale is seen both as a great victory and a terrible defeat. For most Host-Keepers, this destruction of a chosen favorite of the King of Kings represents a terrible setback for the nation. Yet for those who find some nobility in the Ancient Folk, or possibly worship them today, this was seen as a great defiance against invasion.

In this way, in scarcely more than a generation, Divruel was wiped out. The land was divided between King Egon, who renamed his kingdom Lorden, and the war chief Kedan, who named his kingdom Revellia. Many say this was in honor of the Revali that fought with him against Eugen, yet the town of Revelback already existed, allegedly named for the mythical destruction of the Revali centuries ago. As always, we may never know the truth of this.

Regardless, the five great kingdoms of Milos were at last born: Yvrael (which would be renamed the Yfri Fields around 850 RA), Bastis, Lorden, Austmael (soon to be renamed Ethel), and finally Revellia.

Some spellers dismiss the Lost Age as meaningless quibbling, but most agree that for Milos, the Late Kings Age began with the Khabarese Crusade. Though militarily, the Crusade had a significant effect only on Lorden, this would mark the Peninsula’s first proper reckoning with foreign influence as a political and socio-economic force. All of their prior experience with other nations had strong religious overtones. The Viisianari with their insuperable magics, the Mornal Orckids with their unstoppable steel, and the Monosi Kings of Kings, all presented themselves as divine overlords chosen to dominate the Peninsula, and Milosians were easily convinced by their displays of power, especially the peasantry.

When this new threat emerged from across the Western Sea (now the Sea of Khabar), their world expanded. These invaders did not claim to be gods, nor the avatars of divine power, but merely the faithful adherents to a different belief. Though many were horrified by the sight of enormous wooden structures sailing toward them from across the endless blue and green expanse, the rulers of Milos instead saw opportunity.

Conflicting Histories

Mythological Origins

THE AGE OF MONSTERS

Many Milosian myths suggest that the world was once formless: a mass of shadows held somewhat in place by an ill-defined substance called the ether. Some myths liken the ether to the earth and the shadow to the air, and some the other way round. Some make no attempt to define either, and seem to suggest that those who inhabited the world in this time simply swam about everywhere. Swim they may have, but these substances should not be confused with water, which came later in the Milosion creation myths.

Who were these original inhabitants? Monsters. Enormous, hideous, malevolent, and possessed of minds too great or too small for mortals to fathom, these creatures moved about the world in constant and brutal contest with one another. Unlike the twin gods of the Dragon People or even the pantheon of a dozen or so gods in Titonis, the Milosians believed these monsters to number in the thousands, that their breath continuously burned all matter from the world, and that their roars extinguished all life. For thousands of thousands of years, the Monsters moved about the world of shadow and ether, knowing nothing but pain and hatred.

After thousands of generations of terror, the Hadrash were born. Though the children of the Monsters, the Hadrash had some semblance of what we might call mortal intelligence. They had no mercy or love in them, but they all desired to end their own suffering, and therefore sought to end the reign of chaos the Monsters maintained. Many battles were fought, yet never was a single of the Monsters defeated, for they were born by torment, and would rise again even from seeming death. Many of the Hadrash were destroyed or even corrupted into Monsters themselves as a result of these wars.

After a thousand years of battle, the King of the Hadrash (in some myths, the Wizard of the Hadrash), looked into the shadow and ether and bound one of these two substances to his will; which one varies with the telling. This substance he caused to fly up and become the blue sky, and from it fell an endless rain. For another thousand years the Great Rain fell, and the Hadrash hid from the Monsters as the world was reformed. The Great Rain gave weight to everything, and the other substance, either ether or shadow, was fused into earth. Many Monsters were buried beneath the heavy earth, defeated where no weapon could prevail. Those that were not buried were drowned beneath thousands of gallons of water, trapped somewhere in the deepest reaches of the seas.

As the Great Rain began to dry, the King of the Hadrash ordered its people up onto the highest points of land, but many were unprepared for this order. Some say they had begun to fight their own wars amongst themselves, and would not give up the lands they had won even as those lands were covered by the seas. Others say the Hadrash had begun to discover love and sought out their friends and cherished ones and even their own children as they drowned. Still others suggest that, though the Monsters had been vicious beyond all thought, that many of the Hadrash still loved their creators and could not bear to abandon them, perishing beneath the seas as they tried to rescue their brutal parents. Even the King of the Hadrash did not survive the Dying of the Rain; whether because of war, love, or duty, we cannot say. The Hadrash who made it to the surface were few and disorganized, and roamed the landscape as the monsters of their own age.

Some say the Hadrash would become the Sembraxi, or Giants, one of the clans of the Aernigh, or Ancient Folk. Yet the Sembraxi were described as fairly human in appearance, if unusually large: sometimes brutish and sometimes beautiful. The Hadrash, meanwhile, were all twisted and hideous, each uniquely malformed and monstrous.

Others suggest that what we call the Hadrash were those that fell beneath the Rains, and that they became twisted by drowning over and over in the new world of water they had created. Many myths speak of the Hadrash coming up out of the water to fight wars with the Aernigh and later even the northfolk who would come through the Pass of Peril to become the first Milosians. These same people often suggest that the few Hadrash that escaped the Great Rains would become not only the Sembraxi but all the clans of the Ancient Folk, cursed to war against their families that drowned beneath the seas.

More than anything, these myths explain why Milosians were so reticent to venture into the seas, even as other nations began to master the waves. They lived in fear of the Hadrash, and a greater terror of the Monsters that dwelt far below, in the depths.

THE SATARIAI CREATION MYTH FOR MILOS

Though it is the most popular faith in the world, Satariai is fairly new to Milos, having only taken hold during the Khabarese Crusade, and rarely stretching outside of Lorden. Still, they have their own tales of the birth of the Milosian people, carrying obvious influences from the ancient Aernigh myths.

In this myth, a great Wizard named Sthinad sailed a ship from across the Golden Sea to land on Milos. It is not clear if Sthinad is a Yenai Wizard or an Orckid Wizard, saying only that she used her great magic to birth the rivers and the mountains and the forests. The earth, jealous of the power Sthinad held over it, vomited devils out of the ground to challenge her. In most versions of the myth, these devils are clearly meant to be the Aernigh. Sthinad always defeated them, but grew tired of living in constant wariness of their attacks. She cried out to Satar, who summoned a bridge of light across the Golden Sea, bringing forth Sthinad’s people to join her in this new land. The people built cities and helped push the devils back. Sthinad reigned over her people for three-hundred years before passing her crown on to her son Childar and sailing west, presumably to Khabar. Magic supposedly left the Peninsula with her, which is why Milos lacks the natural bounty of Yena or Zalja, or Vaina for that matter.

Many versions of this myth cast Sthinad as an unknown disciple of Satar, which would make the Milosians much younger than any other race on the earth. Satariai point to this as an explanation for Milos’ supposedly primitive culture.

An interesting quirk: many Host-Keepers will hang a Host Wheel in their window to repel Aernigh from any nearby forests, rivers, or caves, with this practice being significantly more common near the sea. This habit has spread among the Satariai as well, except they hang flags featuring the Satari Triangle, or three simple twigs bound into the shape of one. This very practice is a matter of some contention in Bagni Canta, where Satariai and Host-Keepers are strongly segregated, and strong ill-will exists between the two groups.

THE MONOSI CREATION MYTH FOR MILOS

The Monosi creation myth seems the most in line with what we know of the origins of Milos. In it, the Milosians are early Monosi who seek to fly the rule of the King of Kings. They sell their souls to the Host of Magic, and for this their skin turns white as milk. The Host of Magic leads them through the Pass of Peril and into Milos to dwell amongst her own people, the devils (again, a reference to the Aernigh). Many of these first Milosians repent their evil and start a crusade against the devils, conquering the land in the name of the King of Kings and pledging him eternal fealty as penance for their cowardice and wickedness.

As ever, it cannot be known if this belief has existed in Milos for thousands of years, or if it is merely a recent import during the Age of Kings.

THE PILLARIC/ORCKID CREATION MYTH FOR MILOS

The Mornals that briefly ruled over Milos were of course well subsumed in late Orckid culture, and therefore followers of the Sixteen Pillars. For Milosians, this simply means that one of the Sixteen Pillars holds up Milos, just as one holds up Monos, Orckid, Vaina, and so forth. Most Milosian Pillarites are in the Yfri Fields, and believe the Peninsula to be held up by Tharanvellion, the Pillar of Beasts and Trees. A few dare to suggest they are held up by Rhesselor, the Pillar of Crowns, but of course most in the area believe this to be the patron Pillar of Monos.

The Sear Age

The Peninsula is one of those rare places that intelligent life evolved separately from the Cradle of Yaalk (where all human beings originally hale from). The Aernigh are called many things: The Folk from Before, the Children of Pride, the Fallen Folk. They were smaller than modern peoples (who themselves were smaller then), had sharp fangs and claws, and are believed to have had pointed ears (though this may be merely the product of magicians and crude drawings from many generations later). They were divided amongst themselves into six clans, which often warred against each other: the Revali of the Rivers (often called sprites), the Glastins of the forest (often called fauns, and who wore pelts and antlers), the Bodoxi of the bogs (sometimes called boggarts), the Darraks of the hills and caves (sometimes called red caps, for they drank and bathed in blood), the Sembraxi of the plains (called giants, for they alone were unusually tall), and the Foulaxi of the southern frozen woods (called werewolves, for they wore wolf pelts and hunted at night). Ancient bones suggest these peoples fought whenever they encountered each other, but largely kept to their own domains.

Naturally, myths run rampant even today that these peoples still exist somewhere. Go deep enough into the woods, and you shall find a Glastin or a Foulax hunting you. Get lost in the bogs, and a Bodox will catch and drown you. Lone miners will be grabbed by a Darrak and dragged into the dark. And many is the man who thought he had stumbled upon a mossy-haired maiden bathing in a stream at night, to his briefly-lived regret. There are no such myths for the giants, though. They lived on the plains, in the open, and were the first to fall before the coming New Folk from the north.

The Wild Age

Like much of eastern Kynaj, the Milosians were originally Monosi, one of the Three Great Peoples of the continent. It is believed they split from the “Pure” Monosi sometime in the Middle Wild Age, after the emergence of the first King of Kings. The King of Kings, if he did exist, was a powerful Monosi warlord who united all the disparate Monosi tribes under his single rule, which he claimed to be divine in origin. Most believe it was a rejection of this rule that led to three groups of people migrating away from the Sea of Trials: northeast to become the Brevessarians (later the Vainans), east to become the Samayans, and south to become the Milosians.

Unlike the Rivers of Vaina or the Wetlands of Samaya, which were uninhabited before the settlers arrived, the first Milosians had to contend with the Aernigh. It is believed first contact between these two peoples took place on the open fields, between early Milosians and the Sembraxi: the giants. Bones suggest some conflicts took place between these two groups, yet although ancient weapons of bone and rock can be found amongst human remains, the giants appear unarmed. Often standing eight feet tall, it may be the giants were accustomed to treading the fields unchallenged and felt no need to research warcraft. It has also been postulated, however, that the Sembraxi were a peaceful people, and that their extinction came merely from the fears of a smaller people, or even from nothing more than the desire to control the land. The Sembraxi were almost certainly shepherds, a trade the early Milosians presumably picked up after the threat of these big people was neutralized.

While we may, perhaps, excuse the extinction of the Sembraxi as necessary for the Milosians’ continued existence on the Peninsula, their wars against the other Aernigh are less clearly motivated. Humans need wood for fires and to build homes, yet the Glastins and the Foulaxi were believed to live deep within the hearts of the forests, the Foulaxi only venturing outside at night. Bodoxi and Darraks were even more inaccessible without strong motivation, and the Revali were even fewer in number than the Sembraxi. Yet still, the Milosians found a need to engage them all in war. Perhaps random villagers had wandered into their domains and suffered the consequences, once too often. Perhaps early folk caught glimpses of figures in the shadows, and out of terror, gathered their superior numbers and marched into the nooks and crannies of the Peninsula. Or, perhaps these Aernigh, many seemingly accustomed to warring against each other, turned their violent customs on their new neighbors and suffered the consequences. Though the weaponry of these two peoples were similar, stone and bone, the Milosians far outnumbered the Ancient Folk, and there is no evidence of their disparate people banding together in hopes of countering those numbers. Some suggest that the Aernigh survive today, hiding away in their holes, their deep swamps, and the darkest parts of the wood. Yet if even our ancient ancestors could root these people out of their homes and unto their ruin, what chance would any such creatures have today?

Regardless, long before the end of the Wild Age, the Peninsula was dominated by humanity. It is believed that the cold climate and wet conditions contributed to the relatively pale complexion of these peoples, though some suggest it is the absence of a soul that makes them so ghast, indicating both their slaughter of the Aernigh and the cruelty of the Mornals who came later, themselves even ghastlier in pallor. In truth, there is not a nation on this earth, from the frigid climbs of Eysland in the east all the way to the Great Savannah of Batalia to the west, that was not built on the bones of people who came before.

Like most Kynaji people, the Peninsulans spent the latter Wild Age split into various clans, usually extended families. There are some traces suggesting mild levels of migration (north in the winter, south in the summer), but by the end of the Wild Age they appear to have settled into tribal communities. The Peninsulans were among the last civilizations to discover agriculture, and in many ways this signaled the end of the Wild Age for them. However, the Imperial Age (or as they called it, the Orckid Age) would not begin for Milos until 1550 IA. This period between the end of the Wild Age and the Orckid Empire’s Conquest of the region, would come to be known as the Age of Gods or the Gods Age. More recently, it has been called the Age of Devils.

The Age of Gods/Devils

Orckid Age

THE AGE OF KINGS, ALSO CALLED THE KINGS AGE

Cenedras’ Conquest

The Lost Age

Divruel in the Lost Age

THE LATE KINGS AGE

Type

Geopolitical, Kingdom

Alternative Names

The Lordslands, the Peninsula

Demonym

Milosians, Peninsulans, Lordslanders

Government System

Monarchy, Constitutional

Official State Religion

Subsidiary Organizations

Deities

- Beithiach, Host of Foisons

- Esakr, the Host of Magic

- Fairess, Host of Fires

- Gleirea, Host of Horns

- Katriss, Host of Hearth and Home

- Lolliseri, Host of Pilgrims

- Penellea, Host of the Hunt

- Rhennes, Host of Valor

- Tulin, Host of Seeds

- Ulthran, Host of Waters

- Verissian, Host of Scales

- Wilminar, Host of Venoms

Location

Official Languages

Controlled Territories

Related Ethnicities

Related Myths