The Opening War: 1680 to 1688

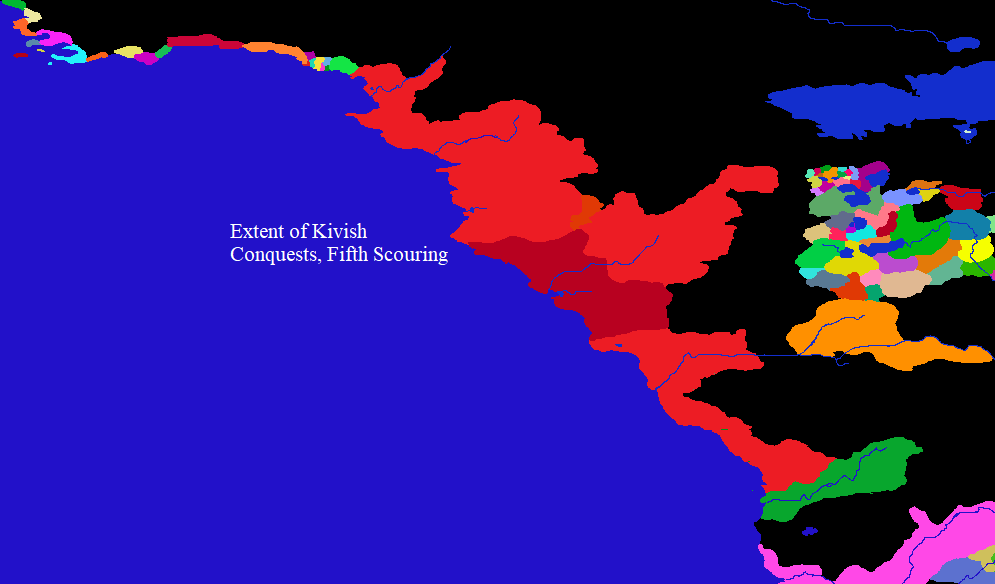

The first years of the Fifth Scouring blend together into the prelude. From 1680 to 1685, the

Empire of Kizen pursued loyalist rebels and invaded small neighboring states, avoiding major conflicts with their two larger neighbors: the

Kingdom of Hain to the South and the

Kingdom of Varinok to the North. Skirmishes occured over contested lands, but the Children played their cards cautiously.

It was in 1685, when the regime felt comfortable and secure in their domestic power, that they launched their grand invasion of

Andrig in the South. Through overwhelming use of

Ederstone weaponry, the Kivish were able to overwhelm Hainish armies and defenses. The neutral city of

Yohenstern was destroyed, the Hainish border marchlands of Haldrang were razed, and Hainish counter-offenses were smashed. It became clear that the modern Kivish army was disciplined, well-supplied, and huge in size - and was far more willing to destroy and move forward than get bogged down in occupations. After just two years, the Hainish frontline in Andrig was destroyed, and the Kivish radicals were moving into

Graefsher. The maze of fortifications and hyper-militarized enclaves slowed the Kivish army, though overwhelming firepower eventually destroyed even the most thorough defenses. By 1690, Kizen had penetrated the Northern marches and was launching attacks into central Graefsher.

A troubling new strategy of Kizen was slave-taking and slave-raiding. Prior Empires of Kizen had avoided this, even during prior Scourings, as slavery attracted the ire of

the Lunar Pantheon and attracted new enemies. The current regime did not care; they saw slavery as a form of mass elimination and removal, a way to turn peasants into loot while emptying their enemy's lands. At first, only war captives were legal slaves in Kizen, and slavery was not generational. Then, in 1690, generational slavery and slave-trading was legalized and institutionally promoted. Eventually, in 1700, mass enslavement policies began to target non-kobolds in Kivish territory. This is all notable in that slavery partially structured the strategies of early Kizen. A new approach was a coastal depopulation strategy: Kivish naval vessels would raid along the coast, taking slaves and sowing destruction. This distracted Hainish feudal lords from the frontlines, denied Hain valuable coastal territory, and depopulated a coastal corridor for Kivish troops to move more freely through. While the Hainish navy tried to resist, the Kingdom lacked a serious naval force during this period, and the warships that did exist were trapped and destroyed in the disastrous Battle of Ultvarn in 1686. Hain hoped that coastal fortifications would prevent raids, but found small groups of Kivish ships more able to cirumvent them than expected. Feudal lords and wargroups were able to respond quickly, but the insistence of these lords and warriors to remain defending their homes fragmented Hainish war efforts.

Kivish Gains: 1688 to 1695

In 1688, Hain found much-needed relief when the Northern Kingdom of Varinok overthrew a newly-couped government and went to war with the Empire of Kizen. Kivish armies shifted from full invasion to raiding in the South while a military force marched North to fight this new front. From 1688 to 1693, Kivish forces focused on the conquest of the North, to protect their capital lands and government. In the South, the Kivish forces focused on distracting and obstructing Hainish forces by creating mass chaos. Monsters were essentially produced en masse, while fortifications were actively torn down to make capturing territory more hazardous than useful. Hainish counter-offenses were mired. Population movements created massive confusion in the Hainish government and society. Hain ultimately stabilized under a single ruling dynasty, who was able to resist challenges to their authority and establish a powerful military machine. Feudalism had failed Hain in the war so far, and this breathing room gave the kingdom time to change into something more utilitarian.

Varinok, however, was not faring so well. In 1693, after five years of bitter fighting, Varinok was completely occupied and their military was fully absorbed into that of Kizen. The full weight of the Kivish military came crashing down on Hain in 1694 - and the Kingdom clearly was not prepared. In 1695, the full force of both armies collided at the Battle of Aenin, in

Graefsher. It was a bloodbath, with massive Ederstone use and new deployment of specialized war monsters. It was clear that Kivish radicalization had opened new military avenues for them: they could deploy walking fortresses of tortured flesh and could use monsters to raise the dead, while the Hainish Knights were mostly doing what they had done centuries ago. Aenin was immensely costly for the Kivish, but it ultimately was more costly for Hain. Pitched battles had favored Hainish knights in terms of battle efficiency, especially since the Varinok front opened, but that was simply no longer the case. The combination of massed Ederstone, new monsters, and massed disciplined troop movements with crossbows made even the smallest tactical errors incredibly costly for massed Hainish cavalry.

The Allies Strike Back: 1695 to 1701

So the Hainish monarchy pivoted. The new Hainish strategy would be to bolster essential lines of fortifications and use them to station small-to-medium army groups; specifically,

Prism mine-castles dug into hills and mountains (which would be difficult to destroy with Ederstone) would act as anchors for Hainish forces to divide the Kivish and deny them territory. This became known as the

Harhoven Plan, as it essentially built a fortification line around Northern Harhoven. Decentralized knightly groups and guerilla war groups would be supplied through the wasteland borders, through interior canyons and hills that would be difficult for the Kivish to raid from the sea or attack on land. If the Kivish wanted to fully break the guerilla supply lines, they would have to divide their forces and build vulnerable land infrastructure for forces in Harhove to strike at. An essential part of this plan was the covert support of the

Kingdom of Nidever, a small mountain kingdom in the North that could provide essential supplies and help anchor the wasteland support line.

For eight years, the Harhoven Plan worked. The Kivish were repulsed at in 1697, at the Grand Sally of Farlin Fields (a prime killing field outside of the prism holds at Farlin mountains), and it seemed that Graefsher was becoming inhospitable to the Kivish once again. And as the Southern front held the Kivish back, the North began to agitate for its own freedom. In 1699, a massive series of slave revolts erupted across the Empire; at the same time, Lunar allies across the wastelands invaded across the Eastern imperial border. Ships from

Boram appeared, raiding the Northern coastline. The cavalry had arrived! These rebellions and raiding parties were put down at great cost, but this internal war soon bled into a new opening of the Northern front: a grand invasion by a Borim coalition in 1701. The Lunar Gods celebrated, at having destroyed the Empire of Kizen, and turned elsewhere to enjoy a Scouring well-ended.

Containment Fails: 1701 - 1709

While the Borim Invasion successful on water and finally ended Kivish naval dominance, it was not the huge military sweep that the Gods assumed it would be. The Northern tribes of Ayvek, North of Varinok, lacked the manpower or supplied to actually make real inroads, and the Borim raiders were unprepared for the Ederstone and warbeasts that came with pitched field battles. The disparate Borim avoided even pitched naval battles, so traumatic were early engagements - though the Druidic leadership did finally unite the fleets to destroy the main Kivish warfleet at the Battle of Shkoklen Bay in 1704.

Unfortunately, the Kivish had been building their own new military apparatus in the South, and were going to launch it regardless of the reopening of the Northern front. A major opening for a renewed Southern campaign came with the fall of the Kingdom of Nidever, that small mountain kingdom that was an essential anchor point for the Hainish guerilla campaign. Then, in 1703, came the surprise attack on

Kamminfost, a supposedly untakeable fortress that enabled Kivish mountaineers to invade under-defended parts of Yeinshtotten. Three main fortifications served as the basis of the Harhoven Plan: Farlin Mines, Yeinshtotten, and

Artoril. With 1703, one of those three was suddenly taken. The prisms of Yeinshtotten tunneled down and survived, but their garrison was destroyed and the strategic point now served to launch Kivish raiding parties. With Yeinshtotten and Nidever both captured, the supply line to skirmishers in Graefsher suddenly stopped - and knowledge of their positions was revealed. The main force of the guerillas was wiped out, with only a small force of cats and plucky rebels (led by the now-famous

House Hunain) remaining.

A disastrous counter-offensive by Hain and a swift capture of Farlin Mines in 1704 by the Kivish effectively spelled the end of the Harhoven Plan - and Lunar illusions of victory. If anything, 1703-1704 led to far more intense Lunar involvement in the war, as it became clear that they had failed to properly communicate Kivish battle plans in a timely manner due to a mix of not taking the threat seriously and inter-god competition. The Lunar Gods helped unify the Borim raiding groups and played a major role in bringing the Northern and Southern allies together. They also undermined Kivish supply lines and sponsored slave revolts in 1704 - 1705, enabling a successful Hainish counter-offensive in 1705. Hainish initiatives and allied cooperation kept the Kivish from acting on their victories for half a decade, but ultimately proved unsustainable. In particular, the Northern tribes were completely subdued in 1707 and Borim naval support began to suffer from over-extension; in 1708 and 1709, Borim fleets had to cut across the open ocean to conserve supplies, and vanished from

Leviathan attacks. In 1709, Hainish forces were simply unable to keep up the pressure, and the gate to

the Delent finally fell.

The Kivish Moment: 1709 to 1722

After thirty years of war, the war began to slowly unravel into chaotic violence - but this was a long, gradual process. Total disorganized incoherence didn't actually start until 1722 - in the meantime, the Kivish held the advantage, and pressed ever deeper into enemy territory.

The period of 1709 to 1715 is the first period of Kivish power, during which several horrific campaigns devastated and razed the region known as

the Delent and attempts were made to push into the

Hainish Heartlands. This period ended in 1715, when Northern Stildanians rallied once again under the Lunar Gods to attack Northern Kizen. This went less well than before; in 1716, the Kivish released living, endlessly expanding oil-fire that swept over the Borim fleets (though it also caused immense coastal damage to themselves). In 1719, the Kivish finally subdued the far North and began a war of skirmishing piracy with Boram.

In 1718 - 1719, while the North was subdued,

Artoril, the last Hainish fortress barring the war to the Heartlands, fell. This unleashed a frenzy of violence that entered the very core of Hainish territory from 1719 to 1722. Ultimately, the Kivish failed to seize the final fortresses of Hain before their own government toppled inwards.

The Calamitous Chaos: 1722 to 1728

Kizen had been facing internal resistance for decades - first from slaves, then deserters and smallholders, and finally from rebellious feudal barons and military families who wanted the Kivish to capitalize on their victory and end the war. A smallholder rebellion in 1710 failed but seeded the countryside with partisans; signs of serious elite resistance began in the early 1720s, as the Heartlands Campaign proved excessively costly and began to seem unnecessary. It began to be necessary for the Kivish Empress to personally oversee the Heartlands campaign, to prevent sedition. This allowed Hainish champions to slay her in early 1722. Mounting resistance on all levels of society put pressure on the selection of a new Children of Verkohn Empress; some saw this as an opportunity for a favorable peace. Instead, hardliners within the faction chose an extremist. Other candidates divided the army and the landlords, and set up their own headquarters to contest the selection. Civil War broke out, the culmination of nearly half a center of growing frustration bursting forth. A group of moderate landlords began to form, who sought to condense the peace faction into a single candidate, who could at last unite the Empire in peace in 1726 - though this was dashed by the extremists, who were ruthless enough to break the opposition down and eventually regain control of the Empire in 1727. Even after this point, though, there was no returning to Kivish Power - the end of the civil war meant costly purges, reorganization, and resistance as the leadership raced to be the most extreme in their dogma.

The civil war should have meant a Hainish victory, but relentless use of Ederstone weaponry only led to a new wave of monsters attacking the vulnerable remnants of Hain. The Chaos saw Hain reclaim the Heartlands, Delent, and parts of Graefsher, but Kizen in chaos was nearly as bad as Kizen in order. The Northern alliance was similarly spent, too weak and too fragmented to capitalize on the moment. But, the allies recovered, as Kizen only grew weaker. Finally, in 1728, right as the Empire was reunified and trying to march back to its prior gains, the Hainish army defeated the reformed Kivish forces at Salhov - scattering the invasion and allowing for a total reconquest of Hain and

Andrig. Kizen's aggression was done for; now it was on the defensive.

The Long War: 1730 to 1750

The following decade of violence was on-and-off-again war, between two powers that had minimal economic capacity to meaningfully conduct war. This is often called the

Long War, and it was known for both its periods of rapid de-escalation and its sudden re-escalation of intense violence. During this period, the Empire of Kizen began to moderate its politics, and large landholders were able to pressure the extremist faction into backing down. The species caste system slackened somewhat, and a peacetime economy was allowed to develop. The Long War period is typically seen as ending in 1740, when Hain finally captured

Trostev and negotiated a peace settlement with Kizen. While formal hostilities ended in 1740, Hain's Questing Knights refused to stop their own raids. The Kivish moderates were humilitated and undermined by these rogue knightly attacks, and the radicals were able to reconsolidate control over Kizen.

In 1743, war re-ignited on a massive scale between Kizen and the coalition, ending in the "False Victory" of 1744, when Hain and its allies captured the Kivish capital of

Eveko. Massive retaliatory Ederstone use ravaged the Kivish heartlands and devastated the coalition's armies, and the allied coalition agreed to a white peace in the autumn of 1744. This False Victory was ephemeral; violence sparked in the summer of 1745, and by spring of 1746 the Hainish-Lunar garrison at Eveko had been slaughtered. War sputtered from 1746 to 1748, with intermittent months of war and peace. Finally, in 1748-1749, a Kivish political coup led to the Empire fragmenting, and the Children retreated to

Rumakel - along with almost all of the Ederstone weaponry.

For a year, a shaky half-peace fell into place. Fundamentalists and moderates fought regularly in the streets of Eveko, with an allied puppet government barely holding on; horrific flesh-warped weaponry and Ederstone projectiles waited to be launched from Rumakel, held by extremists demanding the return of their empire. Disease ran rampant, monsters roamed where they once had not. Finally, in 1750, the

Week of Cleansing took place: a brutal, coordinated political slaughter of the Children of Verkohn and their allies across Kizen. Paladins acted as judge, jury, and executioners in a massive purge of fundamentalists, the holy city of Rumakel crumbled, knights turning monster even as they slew the wretched flesh-warped weapons of the city stockpile. It is remembered fondly now, but it was at the time a week of intense, senseless, monstrous violence. But it was the end, at last.

Comments