Humoh

Origin

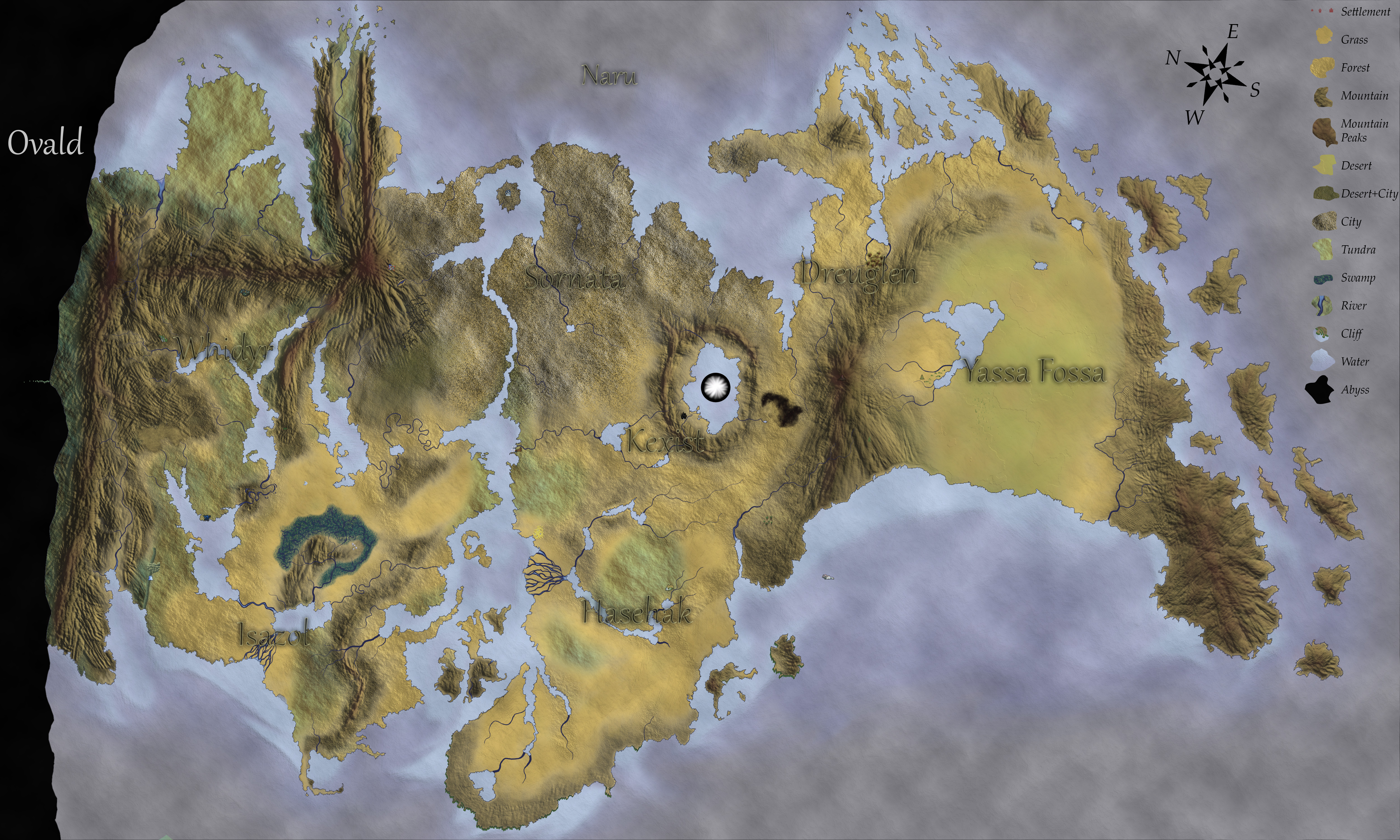

Humoh was among the first languages to be used over a wide geographical area. The language is one of the more well known dead languages, as it has branched off into several commonly spoken languages today. As the language spread, disparate cultures began to change the way they spoke, eventually no longer speaking the original language.While it’s offspring languages have been heavily influenced by other languages, like in the case of Thoos and a;O;u;, Humoh is largely an isolate language. Originating in the predominantly humi populated area of north of City of Sornata, the sounds are easiest for the primary speaker’s palates.

It is believed the language is at least as old as Haseh, if not older. But, because of a humi’s shorter lifespans than drake, the language more rapidly evolved from generation to generation and more rapidly diverged. Others speculate that it is the humi’s culture that caused the language to die, as drakes of southern Hasehak were more opposed to a change in tradition. Whatever the case, Humoh is no longer spoken as a primary language and is saved for scholarly purposes.

See Writing for details about the origins of burn writing.

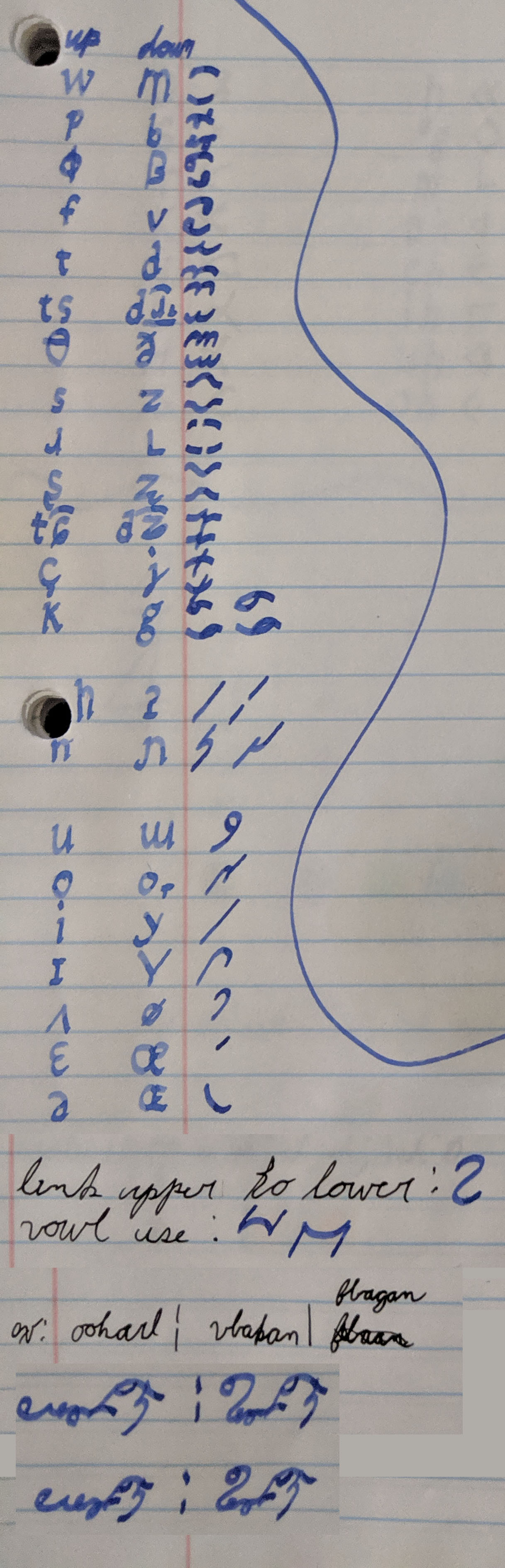

Alphabet

Humoh

| Consonant | Semi-Vowel | Vowels |

|---|---|---|

| w \w\ / m \m\ | H \h\ / - \ʔ\ | O \u\ / Ou \ɯ\ |

| p \p\ / b \b\ | N \ / n \ɲ\ | o \ɤ̞\ / ou \o̞\ |

| f \ɸ\ / v \β\ | I \i\ / Iu \y\ | |

| F \f\ / V \v\ | i \ɪ\ / iu \ʏ\ | |

| T \t\ / D \d\ | u \ʌ\ / ul \ɔ\ | |

| tr \t̠ɹ̠̊˔\ / dr \d̠͡ɹ̠˔\ | e \ɛ\ / eu \œ\ | |

| th \θ\ / dh \ð\ | a \a\ / au \ɶ\ | |

| S \s\ / Z \z\ | ||

| R \ɹ\ / L \ʎ\ | ||

| s \ʂ\ / z \ʐ\ | ||

| c \tɕ\ / j \dʑ\ | ||

| hy \ç\ / Y \ʝ\ | ||

| k \c\ / g \ɟ\ |

Morphology

Upper and Lower

Humoh’s defining feature —which one can still see in writing of Nihyo, structure of both Thoos and Chkoht— is the idea of gender; or, as the original speakers called it, the upper and the Lower. The term ‘gender’ is applied as it is changing a word to form an agreement with other parts of speech, scholars prefer the term used by the language itself.As Gender

Unlike gender, U & L (as will be abbreviated to henceforth) affects all parts of speech; nouns, verbs, adjectives, prepositions, all are included. Each and every phoneme has two forms, an Upper and a Lower —This also means words have an Upper and Lower form which is dependent on the first phoneme’s state. Like gender, U & L have been associated with sex —Humi being of primarily 2 sexes means 2 parts— with the Upper being masculine and the Lower being feminine. As the understanding of the world grew and the discovery of aoreln had the effect of applying the Upper to Dax and the Lower to Suz. This had no bearing in its historical upbringing, but was made into common knowledge until it fell out of use nonetheless.With the change in fashion of one major humi language, that broke into many, so too did the strict adherence to the U & L system. Instead of changing the phoneme to denote gender, child languages started to use affixes and the collision of already-established words in their grammatical system. As far as Kald is concerned, the U & L versions of phonemes were birthed and died with Humoh.

Use

With what could be obvious, the changing of a sound to U & L changes the context, if not the meaning of a word. The obvious example is changing a word to be either nominative or accusative (see sidebar). A less obvious example is for the two words: walk (ougoud \o̞ɟo̞d\) and run (ounkot \o̞ncɤ̞t\). By a Humoh speaker’s reckoning, they use the same sounds, homonyms. It is because ‘run’ ends in the more aggressive Upper that it is used for a more intense activity than the Lower-ending ‘walk’. Where and how a word’s sound is changed to and from U & L could mean a variety of linguistic differentiations between words.The hard and fast rule of the case system is not so easily diverged by the speaker, but whether the following phonemes are Upper or Lower is. If there isn’t any ambiguity of the word used, such as the word for place (Tweu \twœ\), one can change the w & eu to change the word’s effect. Let’s say it’s a place like a religious temple where reverence is required, they may change the word to Twe, to show that it is a place of great import. Or, if the place is (say) a hovel, something the owner wishes wasn’t their living space, they may say Thmeu \thmœ\, to show how ignoble the place is.

This can even be used to create meanings between two different words. Take, for example, walk & run again. One could say for ougHot to mean they are performing an action somewhere between walking and running.

Sometimes, the speaker doesn’t want to change the meaning of a word but wants to change the context behind it. In general, using all Upper for a word (more often for a sequence of words) comes across as aggressive & domineering. At the same time, using all Lower for sequential words comes across as meek & submissive. If a parent is angry with their child, they may speak in all Upper for the more shrill and sharp sounds.

Whether a sound is Upper or Lower, for the most part, is a fairly simple thing between vowels, semi-vowels, and consonants.

Vowels

The Upper form of a vowel is unrounded while the Lower form is rounded. Because humi are able to round their mouths, where many other species like drake cannot, this evolved as an exclusionary tactic. Scholars believe this exclusion is also why many verbs start with vowels. Another species trying to speak the language would have trouble with one of the more critical parts of speech, unable to properly convey their meaning as they can not make the correct sounds. This would further the superiority —not exclusive to humi as almost all areas where one of the Rela (see Creatures) evolves without competition see themselves as superior— the people felt towards others.Consonants

Consonants, like vowels, have two forms. The differentiation between most (exceptions like w & m notwithstanding) is that Lower sounds are voiced while Upper are unvoiced. Consonants, being seen as less important in the cultures of Humoh speakers, are relegated to the less important part of speech that are nouns —Most nouns start with consonants. A noun starting with a consonant also transitions well when speaking, a verb being nearby is more easily spotted even if the noun —able to be placed anywhere in the sentence since the case is delineated— has ambiguity in its case.Ambiguity in nouns occurs often as some dialects have a harder time differentiating the sounds of voiced and unvoiced. And, for species like tsohtsi where all sounds use the same syrinx, hearing the differences is even more difficult. With the interaction between species becoming not a rare occurrence as the world grew smaller (populations larger), the differentiation between voiced and unvoiced fell out of favor.

Semi-Vowels

Semi-vowels, sounds that can be used interchangeably as a vowel or consonant, are almost solely used as connectors when transitioning from U & L. While there are four distinct sounds, they are all used interchangeably and without much effect for which is used —the sound used is typically the one most easily pronounced in any given word. In an example oft used, when a default pronunciation of a noun is Upper and needs to be made accusative, one would affix a semi-vowel after the first phoneme while keeping the rest of the word the same.In the word for plant, dheu \ðœ\, all sounds are Lower, since it’s often used as the subject of a sentence. If one would want to use the nominative form (changing ð to θ), the new form θœ would be unacceptable as there isn’t a transition. The new form would need to be θʔœ. In this particular word, a glottal stop is the favorite semi-vowel to use, it takes less effort to pronounce than θnœ.

A note: some words don’t have these connectors, the rule of thumb being: if the word has a consonant of one position followed by a vowel of the other position, there’s no need for a semi-vowel.

To the past speakers of humoh, each derivation of sound was actually the same sound, semi-vowels evolved as triggers to remind when a switch in mouth shape or vocalization needed to occur. This loose rule meant to make speaking easier, but evolved to be much more convoluted. It began to be used in places it originally hadn’t been, like how it needed to be in place of nominative or accusative transformations. Older Humoh texts did not include semi-vowels in such events.

This rule of using semi-vowels only applies to single words. However, some words include the semi-vowel at the end (like ReN=LeN) due to one reason or another. This isn’t too traditional, ending a word in a state of ambiguity can cause the speaker or recipient a slight discomfort.

While the systems are old and deprecated, Humoh has provided insight into some localized dialects of Chkoht. It would be so much more beneficial if I were to have access to source documents kept in its land of origin. But alas, I must work with what I can get my hands on. Which is not much. In any case, translating Humoh texts into Chkoht, of which there are many witholdend from me, is proving somehow fruitful as I am nearing the completion of my twentieth document. I’ve discovered something too, which I have yet to put into publication. I will not say here, but It should gain me enough reputation to grant me at least a copy or two of some trade documents.

culture

Cultures involving more than just Humi quickly began choosing one sound or another or just dropping the differentiation. However, the written word was kept the same; the written word became more used for trade and religion. And, the missionaries from the east spreading Kanøu loved the idea of including an upper and lower representation in the writing. This spread the language further to the tsohtsi-populated east. Unfortunately, as stated in Consonants, tsohtsi were one of the species that had difficulty with the spoken word. So, while the written word can still be found to this day in sacred texts, it is written with different phonemes and grammar to match modern languages (Thoos being a major adapter).

Historians debate on if the Upper is the representation of the sky (quicker, sharper sounds) & the Lower as the ground (gruff, rumbling), or if that was the Kanøu revisionist history. Documents uncovered in the later-touched western part of Sornata give hints that the reason may be more to represent inside and outside. The people who generated Humoh came from the building-blanketed City of Sornata. If there were structures everywhere that divided the world into shadowed interior or cool-air exterior, it would make sense that they would somehow involve this in their culture and thus their way of speaking. Others theorize that some sounds traveled better outside (the Upper (to better transfer sound through open-air)) and others inside (the Lower (to better transfer sounds through walls)).

Historians debate on if the Upper is the representation of the sky (quicker, sharper sounds) & the Lower as the ground (gruff, rumbling), or if that was the Kanøu revisionist history. Documents uncovered in the later-touched western part of Sornata give hints that the reason may be more to represent inside and outside. The people who generated Humoh came from the building-blanketed City of Sornata. If there were structures everywhere that divided the world into shadowed interior or cool-air exterior, it would make sense that they would somehow involve this in their culture and thus their way of speaking. Others theorize that some sounds traveled better outside (the Upper (to better transfer sound through open-air)) and others inside (the Lower (to better transfer sounds through walls)).

The addition of semi-vowels in places they weren’t originally placed in added a mode for the wealthy and educated to separate themselves from the poor. Adding semi-vowels is more complicated and more of a hassle, so the common being would choose to omit them where it felt unnecessary (such as between two vowels). Because of this, it became seen as low-class not to use semi-vowels, creating more reason to add them to further complicate the language. It didn’t help the perception of the uncouth nature that, when angry anger caused judgment lapses, semi-vowels were often omitted.

This became a joke historians would play on each other, noting how someone is low-class that they didn’t choose the correct semi-vowel. It also became a common saying: Don’t forget your ambiguity. A pun that adding a semi-vowel removes the ambiguity of the two forms while also a cheeky mention of how ridiculous the semi-vowels had become.

Another evolution that stemmed from the U & L system was how numbers were perceived. On the base twelve number system that the people used, numbers 6 and below are all Upper and only change when creating numbers greater than 2&6 [12 base 10]. Seven to twelve are Lower.

This became a joke historians would play on each other, noting how someone is low-class that they didn’t choose the correct semi-vowel. It also became a common saying: Don’t forget your ambiguity. A pun that adding a semi-vowel removes the ambiguity of the two forms while also a cheeky mention of how ridiculous the semi-vowels had become.

Another evolution that stemmed from the U & L system was how numbers were perceived. On the base twelve number system that the people used, numbers 6 and below are all Upper and only change when creating numbers greater than 2&6 [12 base 10]. Seven to twelve are Lower.

Syntax

Humoh has mostly free word order due to the cases; if cases are ignored, the word order is typically OVS. A sentence’s structure comes mostly in the case of a verb’s position (see below). The subject comes last because it is the origin of the effects. In the sample sentence ‘Leudau trRohV-Vau hya paas DeunR’, the eggs (Leudau) are being affected by the holding (hya) which is being affected by the wagon (paas). (see sentence examples on the sidebar) Because wagon begins with an Upper, it is the subject of the sentence. Conceivably, it could go anywhere in the sentence, though it’s not here for demonstration purposes. If the word for wagon were to move, so would the verb.Verbs

Verbs always come before the subject of the sentence. Since there isn’t a case marker for what is a verb (and some verbs may be ambiguous in some homonyms), the verb is placed to the left of the thing doing the action. Adverbs tend to precede the verb or be placed at the beginning/end of a sentence.Nouns

Nouns have use cases, so they can be placed anywhere in the sentence. Nouns exist as one word so articles are prefixes to the noun (ex: thepark, waitingroom). If a noun is ambiguous as to its purpose in the sentence, placing it in order or adding markers like a preposition (used as prefixes) can be implemented. Determiners are apart from the noun and come after.Adjectives

All adjectives that are attached to a singular noun are written as one word. Unlike the nouns or verbs, adjectives come after the noun they’re attached to. What the object is, is more significant than its descriptors.Dictionary

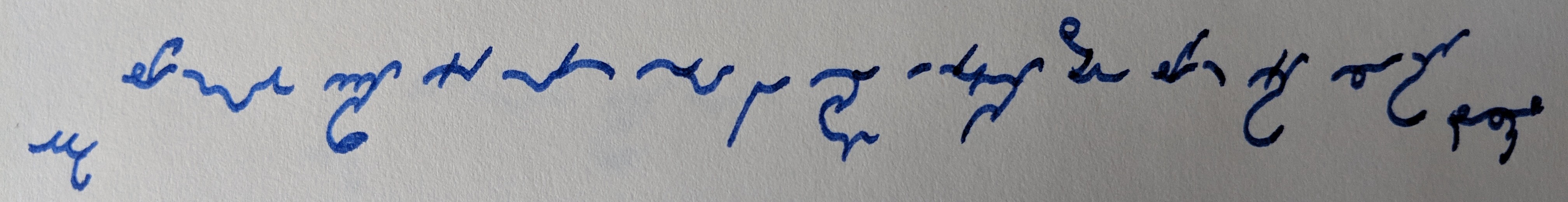

Sentence examples:

- Create the light from me: çɤ̞ cɹi wʏ, cɤ̞β tɪs

- There are 30 eggs in the wagon (eggs of 30 held in ownership of wagon by gift exists ): ʎœndɶ t̠ɹ̠̊˔ɹɤ̞hvvɶ ça paaʂ dœɲɹ

Author's note: I made this writing over a year ago (as of sep 5, 2020) and just found it. I tried to translate it. It probably made sense from a previous itteration of the writing system (as it includes deprecated symbols). It's now gibberish, but gives an idea for what a sentence could look like.

Cases

All cases are defined by prefixes- Nominative: First consonant is upper

- Accusative: First consonant is lower

- Genitive/Dative:

The default prefix for a genitive and dative case is to: (1) add an ‘n’ If a word ends in a vowel (2) extend the consonant, if the word ends in a consonant —this extends to both owning nouns & verbs.

If one so chooses (such as to be more clear), they can be more specific with their dative case. If the verb is being forced upon the recipient, end with ‘ð’. If the verb is being gifted or unforced, end with ‘θ’. If the word ends with ð or θ, change the sound to match the forcedness and extend the sound. It’s used as a marker for volition as well. - Instrumental: Pause after first sound of word

- Vocative case: Punctuation only

Affixes

Suffixes:

Hyoɹ /çɤ̞ɹ/: To make the verb into a title for someone who acts in accordance to that verb (ex: saX=zaZ (hunt) becomes saZhyol=zaZhyol (hunter))T: To make an adjective out of noun

Past: Ah |Present: Ee | Future: Oh: Used when making a noun to a verb append

ETC

AbugidaNucleus is obligatory

Comments