Gwalan Republic

The Sunekan Republic of Gwalan is a realm struggling to reinvent itself. It sits in one of the cradles of ancient Sunekan religion, a land once the seat of a sprawling empire. It is densely populated and its lands are rich and abundant. And yet for all these "legacies of greatness", the wounds of the past run just as deep. The invasion by Calazen in 1870 razed much of Gwalan's cities and left scars that are visible today. And while Gwalan may have a history of empire, it has spent far more time being partitioned and subjugated by other Sunekan republics.

This is all to say that Gwalan is a land that knows itself as a pillar of the Suneka, but lacks the material riches that comes with that. It is a republic that feels robbed of its identity and history: a destined superpower always kept from reaching any potential by jealous neighbors and vicious foreign invaders. This sentiment has coalesced into aggressive Sunekan zealousy: hyper-republican government, rejection of foreigners and foreign influence, and pan-Sunekan religious militarism.

While this has kept the young republic together, it also threatens to destroy it: infighting over who exactly is a better kind of citizen has plunged Gwalan into civil war, belligerent foreign policy has made Gwalan some dangerous enemies, and rejection of foreign trade has hindered the republic's urban development.

But if Gwalan survives this fragile moment, it holds immense potential. It is unusual among Sunekan Republics for its casual militarism: the war against Calazen led to the arming of many citizens and to the incorporation of military training in schoolyard education. Gwalan has access to great supplies of saltpeter, iron, lumber, and food, which the republic has devoted great effort into mass producing. A stable Republic of Gwalan would be able to win over states far larger than itself- it has the potential to become an empire, if it wished to be.

Structure

There are two layers of government present in Gwalan: the central government (which is fairly powerful and controls the general affairs of the republic) and the regional governments (which manage the local affairs of the seven provinces).

The central government is made of four interwoven parts: the Tlakra, the Guardian Council, the Congress, and the High Court.

The Central Government

- The Tlakra acts as the chief military executive and makes day-to-day diplomatic decisions. They are elected by popular vote every five years.

- The Congress of Gwalan is made of representatives from each of the seven provinces and acts as the supreme governing body. It is fairly small, with a representative for each local municipality elected locally every five years. This is theoretically representation by population, but in order to re-draw districts and add new representatives there needs to be a census, which requires cooperation by all four branches of government and the regional government (and therefore rarely happens).

- The High Court is headed by the State Priest and is made up of the ten most senior priests in Gwalan (with the State Priest having two votes instead of one).

- The Guardian Council is selected and approved by the joint effort of the High Court and the Tlakra. It is essentially a cabinet of high-ranking bureaucrats that manage the state bureaucracy and can propose legislature.

-

The Regional Government

- Asarum, the capital province and most prosperous and powerful of Gwalan. Asarum lies in the East and holds disproportionate financial and political power

- Tezitazi, Southeastern province and trade hub of Gwalan that has a traditionally close relationship with Asarum

- Laprucala, a Central province known for its extremely rich farmland; often quite detached from politics, but recently dragged in by the escalating Ezeluri Land War

- Korakoza, a Northern mountainous province currently enjoying a bustling iron industry

- Kuaruza, a Southwestern province known for its ranching that has declined in recent years.

- Ezeluri, the Westernmost province and 'problem child' of Gwalan. Disliked by other provinces for "collaborating" with the Calazan invaders that used it as a headquarters, Ezeluri has been denied many of the rebuilding programs that healed the rest of Gwalan. Economic exploitation and political marginalization has exploded into a civil war there as of 2017.

- Takaruza, the Northwestern plains province known for its fierce resistance to Calazen and its militarism. Takaruza's horrific suppression by the invaders has left it with a depleted population and few urban centers. For its contributions and because of its poverty, Takaruza is not taxed as a province by the Republic. Of those, the last two and the first will be important

Culture

While critics of Gwalan accuse the Republic of suffering from cultural deviancy, Gwalan has furiously objected. Gwalanan quirks are simply signs of proper Sunekan conduct in the face of outside intervention, the Republic has argued.

History

Early History

Gwalan is one of the earliest adopters of the proto-Sunekan religion, with Sunekan communes dating back to the 3000s DE and the first Sunekan city in Gwalan dating back to 2000 DE near the modern-day town of Atokaba. Much of this early history is fairly repetitive: from 2000 DE to 390 ME, Gwalan was dominated from between four to ten states, which would occasionally feud. It wasn't until 410 ME that one of these states would occupy enough land to claim all the Gwalan Valley and name itself the Sunekan Republic of Gwalan. This was by no means an inevitable merger, but rather the life goal of the Imperial Founder of Gwalan: a now-legendary lawmaker and Tlakra by the name of Adakun the Great. Adakun preferred guile and diplomacy to military action and only entered a small handful of wars from 390 to 450. Most of these were with groups known as the Kunonek: highly militaristic semi-heretical groups that mostly wandered along the Gwalanan plains, but had a few successful militaristic kingdoms as well. Rather than eradicate these groups entirely, Adakun kept their most skillful and their most impressionable warriors and elders aside in their own community. From this group, Adakun had a mystery cult founded: The Blades of Tonikora. Tonikora was the spirit of the stars and the first solar, and is the guide for all who are lost. So the Blades would be the hands of Tonikora, guides for "lost" kingdoms to find a peaceful home in Gwalan's imperial embrace. These assassins killed disloyal bureaucrats, opposing monarchs, and any threats to 'regional peace'. Internally, they somewhat resembled a death cult, but this was seen as a small price to pay.

This death cult was the perfect environment to produce an assassin to which no equal has lived: Amati "the First Blade", an ambitious and eager members of the Blades that clambered the hierarchy from a young age. Amati was a deeply unstable character, who took the already-unstable Blades out of the Republic's control and onto a horrible international rampage of coups and takeovers. Amati carved a path across the Suneka from 490 to 530, forging a tributary "empire" of immense proportions. Amati was ultimately killed by a swarm of ghosts led by the former Monarch of Tuzek, Yezok, who proclaimed himself "Spiritual Emperor" of all of Suneka. Yezok seized direct control of the Blades, who were formally moved out of Gwalan in 543. Gwalan was initially resistant to Yezok's rule, but quickly embraced the stability it brought to the region. By 580, Gwalan was leading the charge in Yezok's name: invading Akatlan and other surrounding regions to drag them into the Empire of Suneka. In 605, the group that would become The Exorcist's Guild exorcised Yezok, and the Empire quickly decentralized.

The First Empire

The Great Interregnum

From 1200 to 1600, Gwalan was a punching bag for other powers. The Western quarter of the valley was taken by Akatlan, the Southeast was periodically dominated by Matayan and Atupan. The eight republics were plagued by infighting and rebellion. Chaos periodically reigned over the realm, and exiled groups from other realms would use this chaos to carve out their own tiny domains. Some of these groups were peaceful, including minorities and fringe groups from other regions that simply wanted to live in peace. For example, the Wandering Bard Ateki-Ziraz guided their followers to a remote corner of the Unepet mountains to build a small religious community and bard college in 1250. This community was peaceful and would go on to produce generations of traveling healers, but as outsiders to the Suneka they needed a refuge from government religious enforcement. But just as some of these outside groups were peaceful, some were cults, ambitious warlords, and other bad actors that saw the disorganization as vulnerability to be exploited. The worst of this chaos was 1400 to 1430, when the Pangolin Warlock Nuxikua arrived with their entourage from the North. Nuxikua embraced a kind of violent solipsistic nihilism, pretentiously declaring themselves "the truth to the lies of society" as they and their cult preyed on vulnerable communities. Nuxikua ultimately died from an infected wound and their cult quickly devoured itself, but the blatant evil of Nuxikua's group led to Gwalan being seen as a "liability in need of order" by conquest. In 1410, Gwalan's invaders mapped out their intended partitions. But the invaders could never agree on their boundaries and inevitably pushed each other out. When freedom finally presented itself for seven Republics in the Eastern half of the Gwalan Valley, the Republics eagerly joined together in a coalition: The League of Seven.

But just as some of these outside groups were peaceful, some were cults, ambitious warlords, and other bad actors that saw the disorganization as vulnerability to be exploited. The worst of this chaos was 1400 to 1430, when the Pangolin Warlock Nuxikua arrived with their entourage from the North. Nuxikua embraced a kind of violent solipsistic nihilism, pretentiously declaring themselves "the truth to the lies of society" as they and their cult preyed on vulnerable communities. Nuxikua ultimately died from an infected wound and their cult quickly devoured itself, but the blatant evil of Nuxikua's group led to Gwalan being seen as a "liability in need of order" by conquest. In 1410, Gwalan's invaders mapped out their intended partitions. But the invaders could never agree on their boundaries and inevitably pushed each other out. When freedom finally presented itself for seven Republics in the Eastern half of the Gwalan Valley, the Republics eagerly joined together in a coalition: The League of Seven.

The League of Seven

The Calazan Invasion

Modern Gwalan

Modern Problems

Demography and Population

6,000,000 humanoids live in Gwalan: 35% Dryads, 25% Humans, 20 % Hybrids, 15% Prisms, 5% Other. 100,000 cats live here

The vast majority of Gwalan's population lives in the countryside or in small towns, though many residents seasonally migrate to large towns or cities during off-seasons as part of regional community labor agreements.

Territories

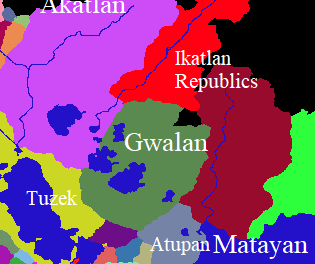

Gwalan is 255 miles long and 285 miles wide, containing mostly humid subtropical forest as well as hot and temperate plains and small mountains. During Spring, the flooding during the early months transforms the plains into a lush psuedo-swamp. Gwalan's geography is dominated by four massive lakes: the massive lake Ezoto at its center, the Eastern half of lake Tlakoto in the West, the large lake Itzoko in the North, and the comparatively small Lake Tiseto in the East.

The Yutara mountains provide a secure Northern border and the smaller Unepet mountain range divides Gwalan from the Empire of Tuzek to the South.

Military

The core of Gwalan's military is a professional standing army of around 9,000 to 12,000 soldiers. In times of crisis, Gwalan can also call upon local conscripts to bolster its forces. While most of Gwalan's conscripts lack any kind of military background, the education system of the Northwestern province of Takaruza includes mandatory military training. As Takaruza pays taxes in the form of conscription rather than food or labor, Gwalan can use these more seasoned recruits to rapidly expand their military without a drop in military efficiency.

Gwalan's massive steel, gunpowder, and bronze production makes it the weapon-forge of the Sunekan heartlands, providing Gwalan's military with state-of-the-art weaponry. Given this and their relatively recent experience facing a large outside invasion, much of their military investment has been in advanced cannons (such as mortars) and handheld gunpowder weapons, supported by heavy polearm infantry.

Adding to the potent slow-moving gunpowder center-force are Gwalan's traditional specialties: light cavalry from the plains and expertly crafted longbows in the lake provinces. While not used to their full potential thanks to the Suneka's disdain for local tradition, both have a presence in Gwalan's military machine.

So far, one of Gwalan's greatest military innovations has gone largely unnoticed: its combination of light cavalry and light artillery to produce highly mobile horse-drawn field artillery. While using animal labor to carry artillery pieces is not exactly new, the innovation of particularly light and quick-to-deploy cannons (even mortars) allows Gwalan's army to quickly move artillery into strategic positions mid-battle. This has been particularly useful against the highly mobile New Mahnekan Revolt of the 2017 Ezeluri Land War, but its potential has yet to be tested in a large field battle. This land war has also created a new breed of Gwalanan war wagons: essentially horse drawn wagons containing tiny 2-5 pound cannons that can pepper forces with light artillery fire. Innovated by the rebels, the standing army has since manufactured their own.

The last unique feature of Gwalan's army is its emphasis on bardic support, mostly in the service of officers. Mystical bards of the Mysteries of Chiun-Masri are often employed by officers as personal healers and guards, as well as magical support for artillery and even major pushes. While these bards often swear oaths against direct violence and are used exclusively for support, their healing, aiming, defensive, and morale support are essential for sudden pushes and keeping vital personnel alive.

Religion

Gwalan, situated in the heart of the Suneka, was one of the first lands settled by Sunekan-style urban civilization in the early Divine Era. As such, its traditions helped shape the Sunekan religion and religious institution.

The Sunekan religion was not always so centralized or uniform. In the beginning, there were many localized forms of cult, often tied to specific locations and artifacts. These local cults were often mystery cults, secretive in their practice and isolated from the main body of the population. Gwalan in particular had a wide variety of mystery cults, and a number of these early cults evolved in Sunekan holy orders- exported as replacements for unique indigenous religious traditions and transformed into tools of statecraft. This legacy remains to this day: Sunekan holy orders are particularly strong here, and mystery cult is well established.

The majority of Sunekan religious administration and belief is the same here as anywhere else- the great purges and reorganization of 1903 wiped away any kind of mainstream religious deviance in the region. However, Gwalan's historical legacy of mystery cult allowed those to survive (and even for religious deviants to escape through creating their own mystery cults). And those populations imported into Gwalan as part of the purges entered with an understanding of Gwalan as a land of mysteries and magic, and so created their own traditions that valued mysticism as a powerful ruling force.

These many mystics are regulated by the Keepers of Olkum, but often work with local standard-sunekan priest communes to interact with broader communities. The most powerful and prolific of the mystery cults also have connections to (and political sway within) related Sunekan Holy Orders. Two in particular are large here:

- The Mysteries of Tetzin-Yutantzin-Moqua, aka the Moquan Mysteries or the Ironeaters, are a prolific cult common in the Northeastern region of Korakoza. The ironeaters worship the mountain-spirit Tetzin, typically associated with stubbornness and perseverance, but specifically the subform of Tetzin known as Yutantzin (the spirit of the Yutara mountains). Unusually, the ironeaters worship Yutantzin as a spirit of change and transformation. They see ironworking as a form of divine alchemy and transformation, a death and rebirth for the very earth itself. Yutantzin is the patron of ironworking and seen as a master of dangerous secret magic related to transformation. This magic transformation is seen as a kind of cosmic self-cannibalism, as the iron is harvested like fruit and then consumed by earth-made forges. As such, the Ironeaters are master alchemists, chemists, and also ritual cannibals (consuming representations of dead members' bodies after their deaths). They are involved with the local iron trade and manufacture acid, gunpowder, and alchemical solutions for mining purposes.

- The Mysteries of Chiun-Masri, aka the Masric Bards are a much more recent group created by the merging of the Masrika religious-ethnic minority and the local mystery cult of Chiun-Nakua. Chiun is the spirit of ravens and crows and the aspect of innovation. The pre-existing cult of Chiun-Nakua believed that Chiun had uncovered mysteries of the universe that could not be expressed individually, but would drive an individual to madness. As such, Chiun-Nakua managed "forbidden magical arts" in the area and generally were known as reclusive scholars that dealt with malevolent ghosts. But over time, their group faded: Exorcists replaced their ghostly functions in the 600s and horrible warlock named Nuxikua made warlockery hyper-taboo in the 1400s. In the Calazan war of 1870, they were decimated after waging a tiny guerrilla campaign, and their remnants mixed with the Masrika Bardic Mysteries. Together, they emerged as heroes- and became extremely popular as a form of bardic mysticism in the 1900s. They have been expanding wildly and have spread to other lands, on route to maybe even becoming a holy order one day.

Foreign Relations

Gwalan is mostly friendly with the other Sunekan powers, with the exception of the Republic of Akatlan, which it perceives as illegally occupying the Northern Gwalan Valley. This rivalry with Akatlan has only deteriorated now that Akatlan has begun funding Gwalanan rebels near the Akatlani border.

Agriculture & Industry

Gwalan's economy is overwhelmingly rural. Maize, rice, wheat, squash, and yams are major crop staples here, as well as acorns, crickets, sugar, cinnamon, and chocolate. Cotton and flax are also grown in large amounts. Horses, cattle, sheep, and goats are all bred and ranched in the flatlands of the North and South. Giant Lobsters and Sudraco are ranched in the swampy lakelands. The lakes themselves are increasingly used as farmland as well: large floating garden-islands in the style of Tuzek (the realm to the South) are common across Gwalan's four huge lakes. Freshwater fish farming is also done there as well.

In the mountains in the Northeast, massive iron and mineral deposits are mined and transported Southwards for smelting and processing. In the lakelands, huge forests are planted and then lumbered cyclically as well for sustainable lumbering.

All of these natural resources are then diverted either out of the region or into the urban centers for processing. During the off-season, farming populations are diverted into these cities temporarily to manufacture goods: smelting iron, assembling items, and acting as temporary construction. Smaller population movements are done seasonally as well for construction during summer, spring, and fall. All this agiven, a reasonable chunk of the populace is effectively semi-migratory, and parts of towns and cities are abandoned half the year as temporary workers move back and forth from the countryside. This precise mass movement is coordinated from above and kept moving through a monumental bureaucracy and policing force.

Trade & Transport

Like most of the Suneka, Gwalan is only semi-monetary: communities directly provide for their members, and food is considered a right for any Sunekan. Much labor is therefore done to fulfill community obligations or to further their status rather than for formal money. Coinage is, however, used to purchase luxury items or surplus goods. Rather than a price-base economic system, Gwalan focuses on gathering community needs from its various industries and communities and fulfilling those internally.

To cover for resources not producing within Gwalan, surplus goods are consolidated and granted in parcels to merchant associations. These associations then work with other republics as well as foreign merchants to sell or barter for goods that cannot be obtained locally. In this chain of production, consolidation, division, sale, and acquisition, major players are granted social capital of sorts- internal measurements denoting the "importance" of a person or group to greater society. This can then be used to acquire land, resources, or positions of power within Gwalan- "buying out" smaller actors.

All of this moves around the vital resources: food, stone, lumber, iron, textiles. And with so much moving without coinage, traditional monetary economics falls apart. 'Spending money' raised from small-scale transactions does circulate, but even this tends to be consolidated by community elites.

This also makes bureaucrats incredibly important. To make a very complicated system simple: local specialists associations organize laborers of a specific type and act as middle-agents between communities and the central government's Guidance Council - specifically the Department of Abundance.

Education

Sunekan countries are expected to provide at least six years of public education for all citizens. Gwalan fulfills this, though education varies by community. Every classroom teaches some core basics: reading, writing, math, government, religion, discipline, etiquette. Schools in wealthy areas are better funded and equipped for preparing their students for ascent into the upper bureaucracy, while schools of rural areas tend to have more labor-oriented programs. Even these labor classes are useful in their fields and are generally loved- but those of the more neglected areas fail to prepare their students for anything but submission. Some even fail to do that.

The schools of Takaruza are unique in that they teach military tactics, discipline, and logistical skills. Fairly well funded and with a long legacy of schoolteacher-warriors, Takaruzan schools funnel their best students into the officer corp and artillery divisions.

As for higher education, each urban center contains a small-scale college of some sort. These are ranked according to prestige, with the highest honors bestowed at Darnema's Gwalan Imperial College.

"Choke, Trespasser"

Founding Date

1903

Type

Geopolitical, Republic

Capital

Demonym

Gwalanan

Leader Title

Head of State

Government System

Democracy, Representative

Power Structure

Federation

Economic System

Mixed economy

Currency

Sunekan Currency: Golden Lions, Silver Foxes, Copper Stars

Major Exports

Stone, food, lumber, sugar, citrus, iron, copper, bronze, tin

Major Imports

Kilusha, tar, silk

Legislative Body

The Congress of Gwalan (unicameral)

Judicial Body

The High Court of Gwalan

Official State Religion

Location

Official Languages

Controlled Territories

Neighboring Nations

Notable Members

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Comments