Sethenes II

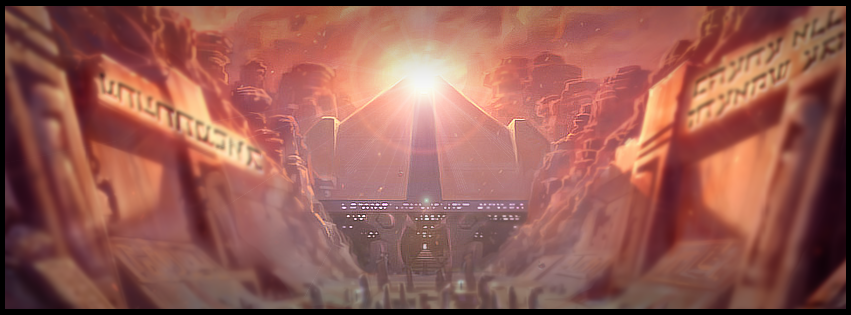

Sethenes II was an Ancient Temekanian monarch and who was the twenty-third and final Pharaoh of Third Dynasty in the 9th Century of the Mithril Era. Sethenes succeeded his father, Nakhor, as pharaoh at the age of 31 and ruled for a total of around twenty-six years. He is largely remembered for his military campaigns in the Mashiq, which culminated in the First Conquest of Jeharoa in 876 ME. Though Sethenes managed to take the holy city from its native rulers, the Ashkelonian Dynasty, his armies were decimated by a series of supernatural disasters. He died only a few days after reaching the Niru River. Fearing divine retribution on the Great House, his niece and eventual successor, Atur-Kesh, ordered her uncle's remaining followers entomb the deceased pharaoh beyond the traditional burial grounds in the Valley of the Shades. This crypt, now known as the Pyramid of Sethenes II, has long attracted grave robbers and treasure hunters, though it is widely believed that the structure, its contents, and the land around it are cursed by twisted magics.

Mental characteristics

Personal history

Little is known about Sethenes' life prior to his campaigns in the Mashiq and his eventual conquest of Jeharoa. Much of the Temekanian records from this period have either been destroyed or were purposefully excoriated in order to purge the memory of Sethenes from history. What does survive comes to us from the chronicler Choim living in the Mashiq some five hundred years later during the Middle Mithril Era.

And in the 9th Century, a pharaoh from Temekan set his eyes upon the glorious city of Jeharoa and felt the hunger of the Lord of Locusts1 consume his heart. He was called Sethenes, the second of his line to be called "snakeborn"2 for it is said that his father often lain with women of that affliction.3Desiring to prove his father's affection was not misplaced, Sethenes resolved to bring to heel the troublesome cities of the Mashiq, as a rich man corrects his neighbor's children.

The pharaoh gathered together a great army, summoning conscripts from every corner of his kingdom. When every nomarch4 had gathered in Temekan, his forces numbered more than 40,000. He then sent for the great slingers and bowmen across the sea in the land of Nejhur.5And Nejhur heeded his call and sent 10,000 to his court. He then sent to the mountains of Shanindar, and called forth the great men of stone and spear.6And Shanindar heeded his call and sent 10,000 to his court. Last, he sent for the aarakocra, those born of birds who dance upon the air. They heeded him at once and sent 1,000 to his court.7

Sethenes marched his army across the Marrow's Quicksand Seas. He arrived at the Blinding Cliffs, where lightning met and nearly struck him. Yet the pharaoh was not dissuaded. They struck with speed and fury, like lions under a moon of blood. And there was much wailing and lamentation as the men of the Mashiq fell, their wives tore their hair and raked their eyes and their children were brought to know Sethenes' greatness.

And the armies of Temekan came upon that shining city o'er the Migdal Plain and saw the step-stones of the divine. Beneath Radiant Uriah's light, Sethenes vowed to take the city in the his name. The pharaoh offered sacrifice of heifer, lamb, fowl, and flank, and then a noble-born boy washed and anointed with ash and oil.8 Yet the One Disk9 shown no favor and the skies darkened before them. Yet Sethenes' resolve hardened further and he ordered his men to take the low places and the high orchards of the eastern hills.

The pharaoh ordered the orchards stripped of fruit and gave them to his men. He had them then cut each tree down, sparing not even the sacred boughs of Porcia and Calorba.10The pharaoh's men fashioned them into great palisades and towers of war. They plundered the land of its livestock to cover their monstrous creations until only jackals and wolves remained.

Queen Ashbahal, Queen of the Jeharoans, herself no stranger to war, sent word to Her Grace's sister—Iktabel, the Queen of Tyria11—to ask for aid. Yet no answer came from the Rock, for not long ago Her Grace had made war on her southern neighbor. The Queen of Tyria reveling in the bitter sweetness, sent word instead to Sethenes and asked that a portion of the spoils be given to her, for the Tyranites had been the ones to ripen the city for him. The pharaoh refused, but offered to take the Rock as payment for resolving the dispute between the two kingdoms.

Then Queen Ashbahal sent for her cousin12 who ruled as King of the Chelmennians. Her Grace's messenger returned with 2,000 Chelmennians, 500 of their number mounted. They met the pharaoh's army at the Bitter Hills of Menethoa, where they were cut down and scattered to the wind. And Her Grace despaired for she now knew that her suffering was the will of the gods. For she had enchanted her husband to love her, despite the prohibition of the Law.13

So virtuous Jeharoa was to be chastised for their Queen's indiscretion.14For one year, the Temekanians lay siege to the shining walls of Jeharoa, now tarnished and ashen. And on the appointed day, they breached the city and Sethenes made great slaughter against her inhabitants. And when Her Grace Ashbahal saw the pharaoh, wreathed in smoke and flame, burst through her fertile gates, the Queen threw herself from the high palace walls rather than surrender to that terrible prince.

In the smoldering glow, Sethenes rounded up many prisoners to bring back to his capital. Amid this, three mages15 attempted to flee, added by priests of every temple in the city. These mages were dressed in queer robes and their heads were shaved and marked with grooves into the skull.16Sethenes had them all brought before him. The pharaoh asked amongst his court of slaves who these mages were, yet only their names and titles could be recalled. The pharaoh then asked the Archbeacon of Uriah why they had conspired to help these three and not the members of his own church.

And the Archbeacon said,

"By the Will of Heaven, they bridge the Known and the Unknown. They hold the Skeleton Key to our city' greatest treasures so sealed by the Light Within. Oh great and mighty Majesty, we are unworthy to speak of mercy in your beneficent presence. When your Majesty frees them of their bonds, let all sing that you were the Virtuous Shepherd that returned Jeharoa to its rightful place amid your flock."The Hungering Secret stirred within Sethenes once more and he was not moved by the Archbeacon's words. The pharaoh called forth the three mages, Joaqin, Dhura, and Abaniah. And the pharaoh asked Joaqin, the master of the three, where the Treasure of the Skeleton Keys lay. But the wise master Joaqin refused to speak. And the pharaoh asked Dhura, the incense bearer17, where the Treasure of the Skeleton Keys lay. But the steadfast incense bearer Dhura refused to speak. And the pharaoh asked Abaniah, the almskeeper, where the Treasure of the Skeleton Keys lay. But clever Abaniah too refused to speak. Enraged at their insolence, Sethenes resolved that all the faithful of Jeharoa be punished along with the three mages. The pharaoh ordered the metal from all the temples of the gods to be melted down and molded into a single hollow piece with a door on one side. Its shape was that of a elephant18, with gleaming tusks and broad ears and a great trunk that curled like a royal trumpet. The priests of the city wailed at the sight and begged the Heavens for deliverance, for their faith was true. Cruel Sethenes yoked the priests to the beast and forced them to drag the bronze on rollers up to the high palace walls of the Sacred Court of Ashkelon19, so that all the city could look upon his work and know Sethenes' power over all things. Again, Sethenes called forth the three mages and asked them to reveal to him the location of their most-precious treasure. And again, the three mages stood in perfect silence. And rage boiled in Sethenes throat. The pharaoh ordered them placed within the belly of the beast and had a cooking flame lit beneath it. The heat within the brazen beast grew, but not a sound was heard from the mages. So Sethenes ordered the heat be increased three times. The bellows were beaten and the fire roared. Still, not a sound was heard from the mages. So Sethenes ordered the heat to be increased another three times. The bellows were beaten again, and all who watched pulled at their sweat-slick tunics. Still, not a sound was heard from the mages. So Sethenes ordered the heat be increased again, until the flames were nine times greater. The feet of the beast began to melt and the bellows' workers collapsed arms stiffened. And yet, not a sound was heard from the mages. Sethenes ordered a courtier to look within the beast to see what to look within the chamber to see what had become of the three mages. When the magistrate did so, his eyes scalded, and a tongue of flame struck him dead. So the pharaoh ordered his grand vizier and court wizard, Hemet—who was known for his cunning spells—to gaze within the beast to see what had become of the three mages. And when Hemet gazed within the brazen belly, he saw the three mages sitting calmly amidst the flames and wreathed with light. And the ground shook, the metal bent, and a great chorus of voices erupted from the beast’s mouth,

“WE ARE THE SERVANTS OF THE SECRET FIRE, THE CHILDREN OF TITAN AND FURY. YOU ARE UNWORTHY, SETHENES, SON OF NAKHOR. LOOK UPON OUR IMMORTAL BONES AND DESPAIR.”The brazen beast twisted and broke with a thunderclap. The whole of the pharaoh’s court fell to their knees and trembled in fear. And when they looked in the wreckage, they found that the spirits of the three priests had left this world. Only their bodies remained in, fully meditative, and bear of flesh and burnt marble-white. The pharaoh’s advisors pleaded for him to accept this omen and release Jeharoa from subjugation. But Sethenes was a proud man and was blinded by the Hungering Secret. The transformation of the mages convinced him of their power and only drove him to uncover their hidden wealth. He agreed to leave the city but did not relinquish any booty or slaves he had taken in the course of his conquest. He ordered the bodies of the mages to be carried in his personal retinue and vowed to return once he had consulted the prophets and astrologers of his own country. Yet in the course of his conquest, Sethenes had drawn the ire of the Gods. They had witnessed the murder of their faithful, the yoking of their priests, and the desecration of their temples. As they crossed the Blinding Cliffs, the heavens darkened and the sun gave off no warmth but shown like the moon on a cloudless night. This heralded the first of seven plagues20 sent by the will of the Gods to torment Sethenes and his agitators. First came the wind, a howling storm that ripped cloth, cut at the face, and tore rock from the canyon walls. The army of Sethenes looked to the sky for some reprieve but saw the clouds only darken. And from above the wind was met with a great slinging of hailstones, sharp and heavy, which lay waste to the land. Those spared the shafts of their foes at the walls of Jeharoa found no fortune in the open desert and fell like wheat on the threshing floor. And as sudden as it had came, the clouds parted and shown the sun ensconced in shadow. Its pale light grew malevolent and the baked the golden sands. Men walked on, their minds lost to the heat, their bodies roasted in their own armor. The soldiers knew they had invoked the wrath of heaven and so compelled the priests of the column to call up to Uriah and ask his Radiance for guidance. Yet when the priests cut open the lamb and examined the entrails, they found no answers only an omen of death. And pharaoh's army turned on their priests, and pierced each of their eyes with hot irons, that they might see a way as the one with the One-Eyed Sun. And only stillness could be heard on the dunes when a great shelf of clouds came over the horizon to block out the pale sun. And all the column rejoiced for with the blood of priests Uriah had been appeased. Scattered then steady came the first silver drops of relief. But as they darkened the earth, screams broke upon the camp. The rain lanced skin with boils and blistered and pierced each man as sure as a spear. Their rupture forced men the size of mountains to their knees and crippled the horse of every charioteer. And after six days, the rains passed and along came a gentle wind that caressed the scars of the weary. And Sethenes clenched his heart, for he knew the Hungering spirit before him. And the host of the Lord of Locusts21appeared on the plain and covered the land such that the ground could not be seen. They burrowed into the flesh, their spawn festering within their wounds. Glutted, they burst from broken men until their swarm filled the dome of the sky. And even the pharaoh had not been spared punishment; pockmarked of face and skin peeled like papyri. A blister in his side festered and black with bile. Still, Sethenes dragged his army north. And at dusk, the pharaoh had his porters carry him atop the crest at Akh Mher.22 And at the summit the pharaoh gaze out upon the red sand plain before him to see the verdant ribbon of Niruland.23Then all was cast into darkness, for Calorba and Acien Tali could bear not the sight of what was to come.24 And the All-Seeing Sun caught pharaoh's soaring hopes and called forth Balan.25And together they summoned forth fire and lightning, bringing great destruction and violence to them all. The stars fell from Akh Mher to the river's banks and creams turned to ether and stone to glass in answer to the fate of Jeharoa. And Sethenes looked upon what he had wrought and felt naught but emptying-grief. The blight in the pharaoh's side flared and he fell upon the ruddy stone, dead for by the will of heaven. Dawn's rosy fingers gripped the horizon to find that less than one ninth of those whom had set out from the Blinding Cliffs with the pharaoh alive. Led by his Majesty's grand vizier and court wizard Hemet, they crossed the glassened lands to the River of their homeland and made their way to the capital. They were met by Atur-Kesh, the distant niece of Sethenes II. Atur-Kesh subdued the remaining members of the late pharaoh's column and with the aid of her most loyal vanguard, she put them to the sword. It was the advice of her most esteemed high priests that their bodies and all of their treasure be removed from the country, lest their accursed deeds desecrate the promised26Valley of the Shades. Her necromancers drew forth Sethenes and all his followers. In the great stony27deserts beyond the Akh Mher, the dead of Sethenes toiled without tire to build a grant tomb to their fallen lord. Over the centuries, Sethenes’ deeds turned to sand and few knew of his life before death. Now, travelers know the Pyramid of Sethenes to be a thin place and the only great pyramid tomb outside of the Valley of the Shades. And while the Ghostdunes are plagued by undead hordes, strange occurrences continually happen around the Pyramid of Sethenes. Many have been drawn to the pyramid in search of the Treasure of Jeharoa. Yet all those whom enter have ne'er returned and none know the fate of them or of the spirits that stir within. Only time will tell if the secret keys of Sethenes will ever be unlocked.

Footnotes

1 Refers to greed, the primary domain of the Unspoken One known as Deverin.2 Little is known about the origins of the Temekanian Empire, however, several legends speak of conflicts between the early aasimar of the Upper Niru Valley and a "snake people" that inhabited the western delta region of the Lower Niru. Some scholars believe that this was an established society of yuan-ti that were ultimately driven out of the area by the end of the First Intermediate Period. These scholars contend that many of these yuan-ti—particularly members of the lower pureblood caste—may have been integrated into early Temekanian society either as slaves, farmers, or concubines. If true, this would be in contrast to the Temekanian alliances with aarakocra communities, which appear to have been more mutualistic than the early conquest and subjugation of these fabled yuan-ti.

3 While it is unknown how exactly early Temekanians viewed the offspring of a yuan-ti and an aasimar, this may explain why many members of the pharaonic court and the priestly temples appear distrustful of Sethenes and slow to enact any of his policies.

4 A nomarch was a provincial governor which ruled over a nome or province in the Temekanian Empire. They were in charge of conscripting soldiers for the state's armies and keeping accurate accounts of all land holdings and tax incomes.

5 Nejhir is a semi-mythical region only attested to in ancient Temekanian writings from the Early and Middle Mithril Era. It is believed to lie somewhere in Eastern Hakoa, likely either along the coast of the Shattered Strait or somewhere along the southern edge of the Mazabar Highlands.

6 The "men of stone" or the "men of spears" is the Old Temekanian name for the people of the Shanindar Mountain Range, who were likely mountain or hill dwarves.

7 As with most accounts of army sizes in Old Temekanian documents, these troop numbers are likely inflated. This can be further proven by the fact that the total number of soldiers given—66,000—fits into ancient Mashiqi numerology.

8 One of the many epithets of the sun god Uriah.

9 Though rare, human sacrifice was an important part of many divine and arcane rituals in Temekanian culture, particularly in the Early and Late periods of the Mithril Era.

10 Though neither Porcia nor Calorba are associated with any particular flowering trees by today's Mashiqi, both were considered important goddesses of arbor agriculture during the Mithril Era.

11 Though not recorded in Choim's account of the conquest, following Sethenes' retreat to Temekan, the city leaders of Jeharoa are said to have relinquished control of the city to Queen Iktabel of Tyria, where she quickly assumed control of the Ashkelonian Dynasty and declared herself Queen of Jeharoa and Tyria. Tyria would in fact break away from Jeharoa only a century and assume total independence from the Jeharoa's Ashkelonian Dynasty.

12 Neither Choim or any other chronicler records the name of this King of the Chelmennians. Very little is known about the Chelmennians or their relationship to the other city-states of the Mithril Era's Mashiq. It appears that they were a semi-nomadic people that inhabited the southeastern foothills and coastline of the Shanindar region.

13 Though today many, if not most, uses of enchantment magic are regulated by contemporary law codes, no prohibition exists in the Heavenly Codex's Law of Heaven. This suggests that the Law referred to was enacted independent of the Heavenly Codex's regulations, a highly unusual change from how we typically think of Mithril Era legislation.

14 Whether or not Ashbahal actually performed enchantment magic on her husband is unknown, as it is quite possible that the author is using Ashbahal's sin as an etiological device to justify the seemingly indiscriminate violence experienced by the people of Jeharoa. It also draws an interesting comparison to the later divine retribution suffered by Sethenes and his armies, which is attested in both Mashiqi and Temekanian texts as well as by physical evidence.

15 In the early translations of this story, the words used to describe Joaqin, Dhura, and Abaniah come from a number of professions including that of hermetic monks, temple priests, and even magicians and charlatans. In later translations from the Palladian Era, the three's titles are all converted to fit the structure of most Heavenly Council temples. The translation recorded here attempts to reconstruct the original language of the text, though it is likely that the author was using descriptors inaccurate to the actual roles of the Keymasters during their lifetimes.

16 Though not uncommon among the early tribal societies of Auloa and Iroa, this text appears to be the only description of trepanning in Mithril Era Mashiqi culture. This is further illustrated by the author's apparent ignorance of the practice.

17 The role of incense bearer was a critical part of Mashiqi religion during the Mithril Era, with the bearer often being associated with exorcisms, ritual cleansing, and demonology.

18 During the Mithril Era, much of the Mashiq and the Sunset Shores was home to a subspecies of elephant known as the Alameen elephant. This species went extinct during the Palladian Era, possibly due to overhunting by the Palladians and habitat loss.

19 Once known as the Sacred Court of Ashkelon, this structure has been razed and rebuilt a dozen times. Today, the Palace of Wisdom, a vast complex built during the Qartagonian occupation, sits atop the site.

20 Older translations do not consider the darkened sign to be a plague in it of itself but rather a herald of the coming calamities. As such, the original number of plagues was six, in keeping with the sacred numerology found in most legends from the Heavenly Council.

21 Though often referred to as the Plague of Locusts, the creatures' behavior appears closer to that of stirges and their larvae rot grubs stage.

22 Ahn Mher is a narrow ridge escarpment made almost entirely of quartzite and located some sixty kilometers south of the River Niru. It's name in Old Temekanian means "mount of glass" and it has long been consider a place of prophecy among the local Marrowmen and the Temekanians of old.

23 "Niruland" is a colloquial term used by the Mashiqi to describe the Niru River Valley, and more broadly, the homeland of the Temekanians.

24 This may be an indication as to the date of Sethenes II death, as Calorba and Acien Tali "hiding their faces" is a popular euphemism for both moons being in their new moon phase.

25 Many common readings of this text claim that the other member of the Heavenly Council he enlisted in this passage was the civic god Balan, who's most common epithet is the Final Judgment. However, most scholars agree that the author intended the audience to infer that Uriah was summoning Telerashi, as she is the sky goddess most often associated with lightning and because the text infers that she was the god responsible for summoning the calamity of hailstones upon the Temekanians early in the passage. Later Palladian Era manuscripts and accounts include all three divines in an attempt to represent as many members in the Heavenly Council punishing the so-called mage worshipping Temkanians as possible.

26 One of the many reasons why gaining employment with a pharaonic court was so appealing in Old Temekan was because every member of the court was promised a burial within the sacred Valley of the Shades on the northern bank of the Niru River. These burials were paid for by the state and because they were within the Valley of the Shades, they were in some ways believed to guarantee safe passage to the afterlife and protection from necromatic magic.

27 Though today largely covered by dunes and classified as erg desert, the region just south of the Ahn Mher was comprised of a rocky hamada plateau during the Early Mithril Era.

Alignment

Lawful Evil

Current Location

Species

Ethnicity

Honorary & Occupational Titles

Pharaoh of the Upper & Lower Niru

Lord of the Great House of Temekan

Lord of the Great House of Temekan

Date of Birth

820 ME

Life

4014 B.S.A.

3957 B.S.A.

57 years old

Circumstances of Death

Killed by divine retribution for the desecration of sacred places during the Conquest of Jeharoa—30th of Radiant Return

Birthplace

Old Temekan

Children

Current Residence

Pyramid of Sethenes

Gender

Male

Aligned Organization

Ruled Locations

Comments