Pagsian Turning (/paːˈɡusiən ˈtɜːnɪŋ/)

(127,840 BP - 113,700 BP)

The Pagsian Turning1 was an age of warmth, comfort, and peace that lasted approximately fourteen thousand years.2

Climate and Ecology

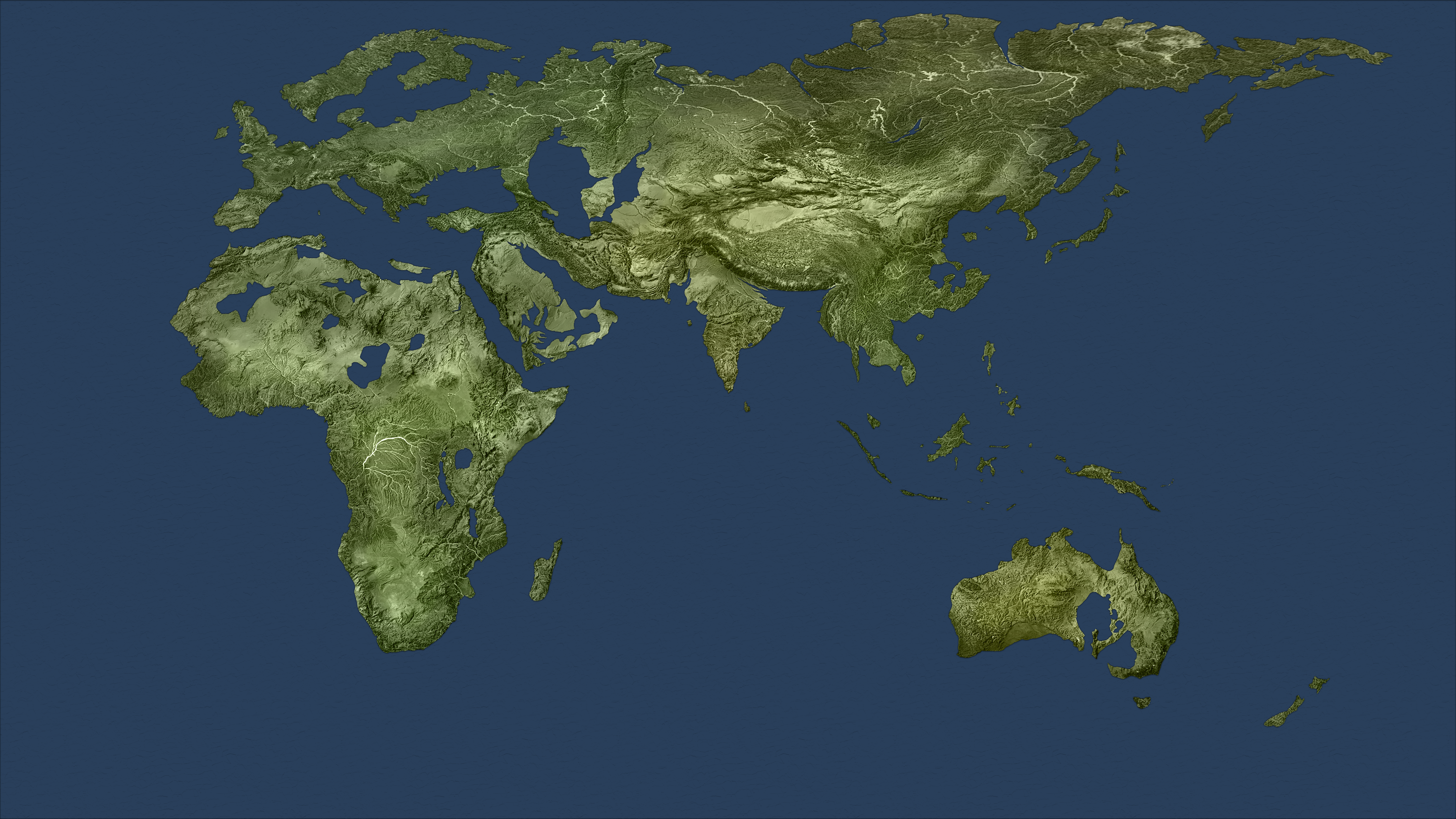

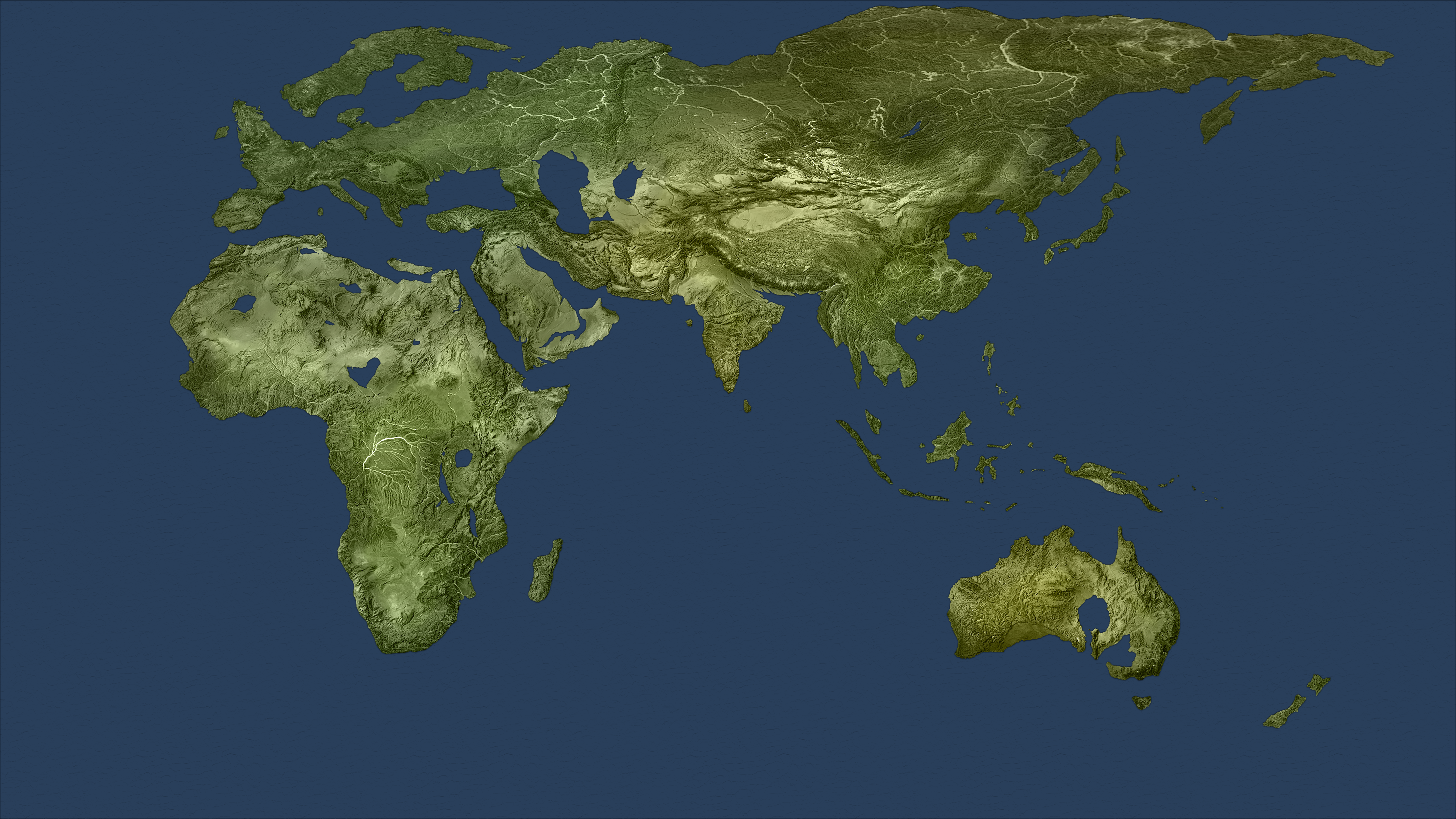

At the height of the Pagsian turning, around the year 125,000 BP, average global temperatures were seven to eight degrees Celsius warmer than the present day, sea level was more than ten meters higher, and ecosystems world-wide were both warmer and more humid. The weather was also more consistent: seasonal swings between summer and winter were less extreme in Europe and northern Asia, and the summer and winter monsoons in southern and eastern Asia were gentle and predictable from one year to the next. Sibir was temperate, and in Chang Jiang Pingyuan, Damara, and Kasai the rainfall and humidity were at or near tropical levels year round. Sea levels were so high that Skáney was an island and Sunda was completely submerged in the Nusantaran Sea, with nothing but a scattering of the highest mountains visible as islands above the water. The result of this gentle, wet climate was a world overflowing with life. Lush grasslands in northern and eastern Africa were speckled with lakes, while Europe and northern Asia were dominated by thick deciduous forests. Hippopotamuses, rhinocerous, lions, elk, and several species of elephant could be found throughout Europe, even as far north as Avalonia. Further south, Kasai and Tanganyika were tropical rainforests populated by large wetland mammals.Localized Anomalies (123,820 - 117,400 BP)

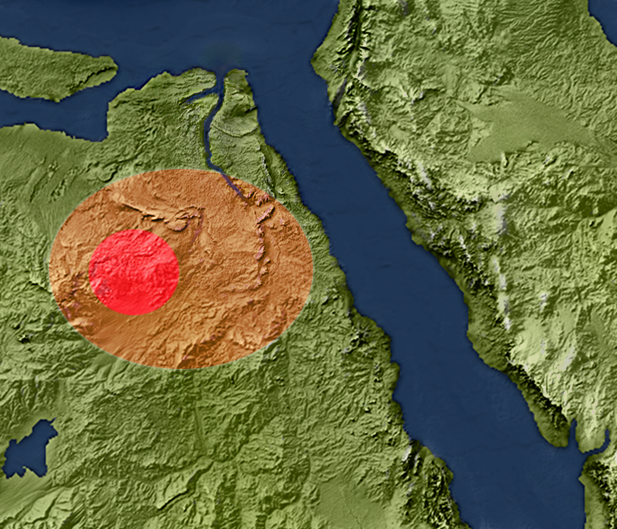

Despite these archetypical "Golden Age" conditions, the climate during the Pagsian Turning was neither static nor perfect. From time to time unusual weather patterns would stir things up in one local region or another and force the inhabitants to adapt. These anomalies became more frequent and more severe in the latter half of the turning. A cold dry spell swept northern Africa in 123,820 BP that caused inland lakes to shrink over a span of a few decades. This forced the humans and animals that had relied on those lakes for food and water to migrate eastward, concentrating in Kemet, Nehsyu, and Punt. The high concentration of human clans in Kemet led to the establishment of the Wadi Halfa pilgramage site: an open air site that groups would return to year after year, in the hope of meeting other clans, exchanging stories, and learning new skills. A little more than a millennium later, central Europe experienced a decades-long drought that led to a surge in brush fires and disrupted the local neander population. Closer to the end of the turning, a handful of cold "dustbowl" anomalies in the mountains of Chang Jiang Pingyuan forced the local denisovan clans to migrate closer to the ocean. In each case, the local climate mostly rebounded but never fully returned to previous conditions.Gradual Cooling (117,400 - 113,700 BP)

During the final three millennia of the turning, global temperatures entered a phase of a slow and steady decline. Sea levels dropped as ice accumulated in the far north, although this change was gradual and caused only minor changes in global coastlines. The biggest impact on coastlines and land area could be seen on the east coast of Chang Jiang Pingyuan, where the denisovan clans were able to expand into new and extremely fertile coastal lowlands. Globally, the cooling climate led to changes in vegetation and animal grazing and migration patterns. Rainforests in Damara slowly became supplanted by deciduous forest, while holly, ivy, and conifer trees spread across Northern Europe. By the end of the turning, summers were consistently cooler and moister all over the world, although winters in northern lands still remained mild.Dakhleh Impact (113,700 BP)

In the autumn of 113,700 BP, a storm of enormous meteors rained down on Kemet in a barrage that lasted for six days and six nights. Some impacted the ground, and others exploded in the air. This superheated the atmosphere and destroyed all life in the area. The center of the impact area was only 450 kilometers from Wadi Halfa, and simply by chance misfortune, so many humans were concentrated in the area that this single disaster killed off almost a third of the human population. The airbursts were so intense that they may have destabilized the atmosphere triggered the new climate conditions that characterized the Recosian Turning.3 More importantly, however, the psychological scarring for the humans who witnessed the inundation of fireballs from the sky was destined to fundamentally change how they experienced the world.Cultures

Each of the three sentient species of the world inhabited a separate continent during this turning: humans lived in Africa; neanders occupied all of Europe; and denisova were spread across much of Asia. They had many traits in common, having descended from a common ancestor. For example, people of all three species organized themselves into nomadic extended family clans of anywhere from 20 to 200 people. However, they also had important differences in both their behavior and their physiology that reflected both genetic differences and differences in the environments they had adapted to. The first cultures of the world were simple, characterized by only a handful of practices that were shared across all clans of the species. Over time, the behaviors of clans in different regions specialized and differentiated to produce different cultures. At the beginning, however, the comfortable climate and abundance of the Pagsian Turning created very little pressure to develop specialized regional survival techniques.4Emergences

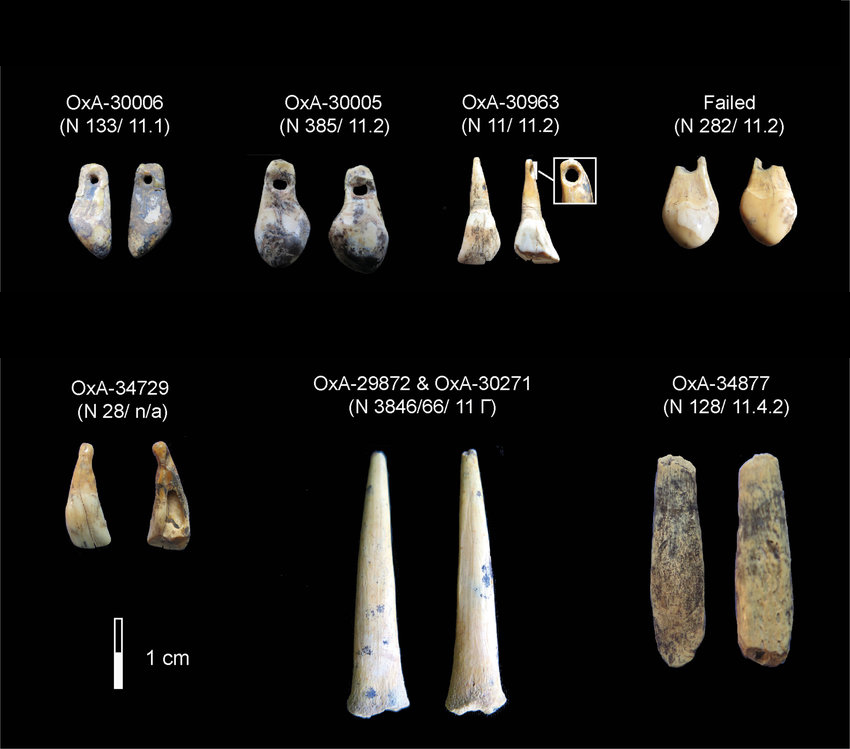

Neanders in Europe had Moustrian culture: they were artists and musicians, captivated by the beauty of nature and inclined toward creating and appreciating beautiful patterns in the world around them. They painted themselves with ochre and covered themselves with feathers. They were skilled in working with stone. They had a meeting place at Bruniquel cave where they carved decorations into the walls and made paintings with ochre and ash. Denisova in Asia had Bah̃iži culture: they were traders and craftsmen, who understood and appreciated the ways that all animals use and manipulate their environments. They carved tools and decorations from bamboo and bone. Their clans were continually mobile, and they actively sought out other clans to trade with as a way to learn new skills and ideas for their craft. Humans in Africa had Aterian culture: they were oracles and trackers, who saw the world in terms of cause and effect and were obsessed with figuring out why things happen and what would happen next. They communicated primarily through sounds and gestures, although every clan had developed its own unique clan language in isolation.5 They had a meeting place at Wādī Ḥalfā that grew in popularity throughout the turning, until it was destroyed by the Dakhleh disaster.Encounters

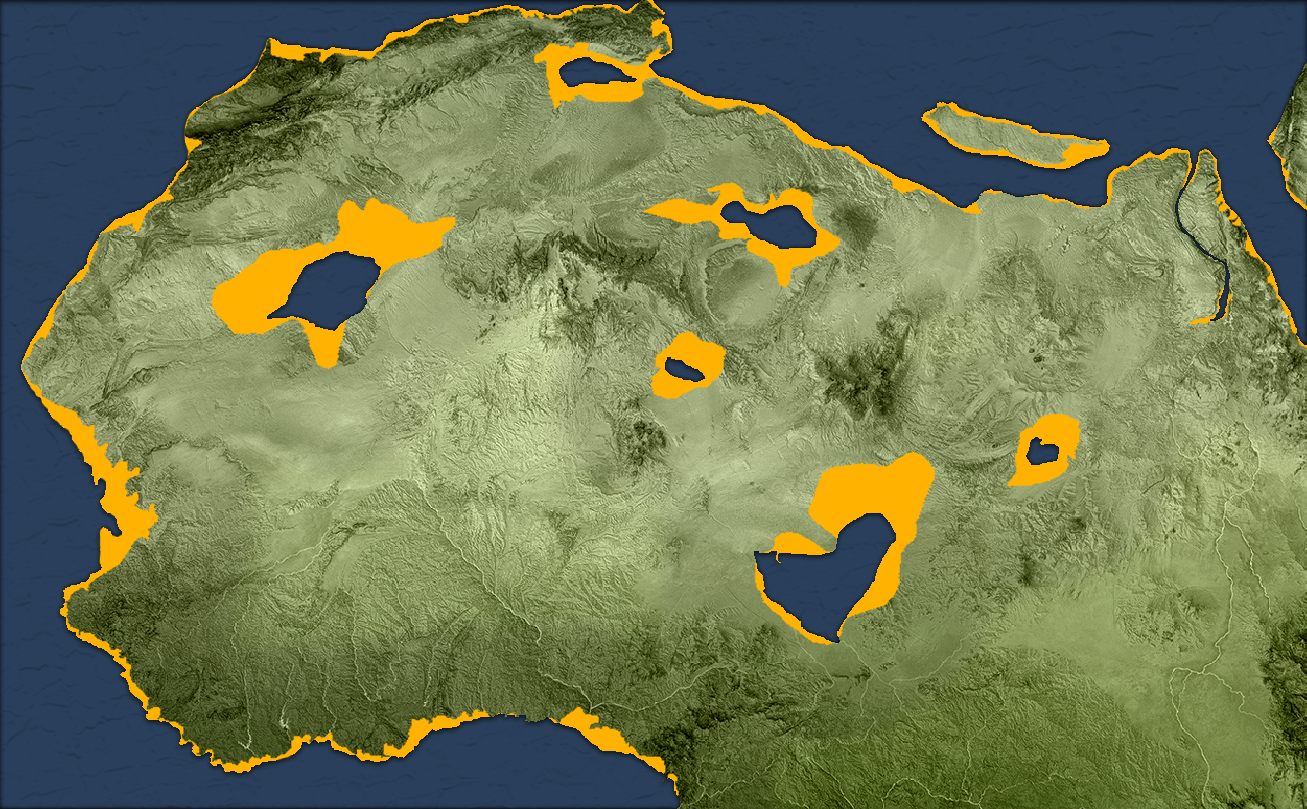

There was no interaction between sentient species during this turning. The population density of all three species was so low that clans could often go for entire lifetimes without even encountering other clans of their own species, much less any other. As nomadic foragers they explored freely within their territories, but they had no motivation to overcome the natural barriers of the mountains that separated neanders from denisova, or the water that separated those species from the humans.6Culture Map

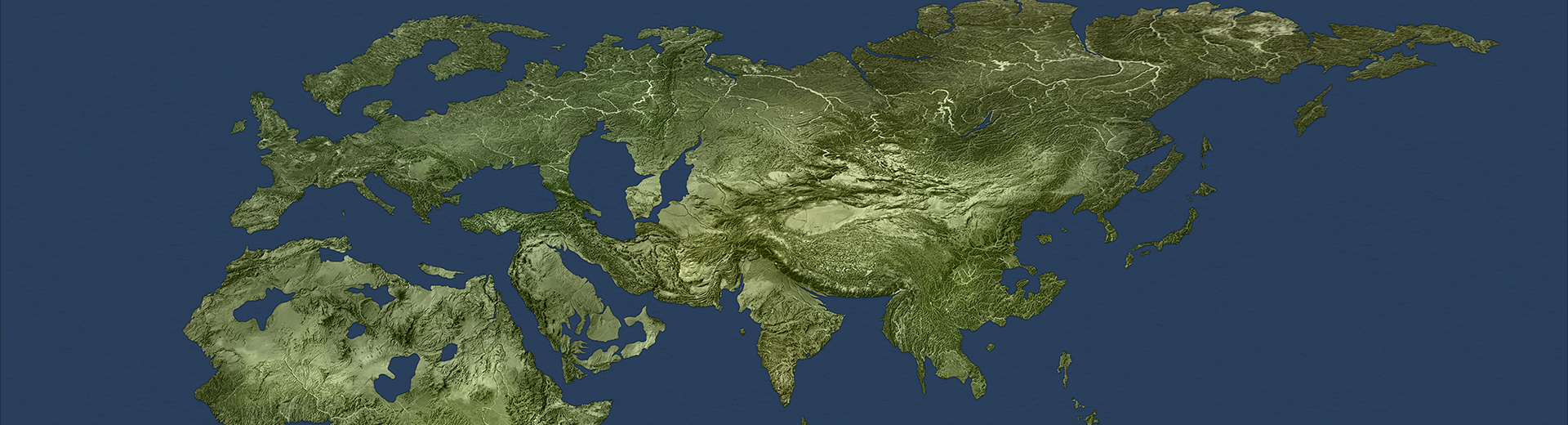

This map shows the general regions most often occupied by clans of the first cultures of the humans, neanders, and denisova.World Maps

Detail Maps

Graphs, Photos, and Illustrations

Footnotes

1. The label Pagsian was introduced by Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie in 75 BP as an anglicization of PA-KA-SI-A, a direct phonetic transcription of the Kuraną word that appears on Tablet EN-8239X. Although unknown to Mackenzie at the time, later researchers have determined the tablet was created by the Acheyawan civilization some time around 3,630 BP, which accounts for the obvious connection to the Yék root pak (fasten, bind, hold together) which also shows up in the etymology: pak - pax - pais - peace. This turning was added late to the ensemble of recognized turnings, exactly because it is so ancient that finding the trail of stories and and references to it is difficult. Nonetheless, the name Pagsian follows in the tradition established from Ficino on of "normalizing" the names of turnings into a language connected to Yék and its descendents. In 72 BP, Henry Steel Olcott proposed an alternate naming scheme for all of the turnings that was based on Pūraw linguistic reconstructions. Olcott proposed this alternative naming scheme overtly as a response to the habit of "normalizing" turning names around yék roots, which he saw as an attempt to erase scholarship and impact from Levantine and far eastern cultures. In the naming system proposed by Henry Olcott, the first turning of the world is called En Nesha'alm. This is only one example of several attempts in recent scholarship to develop naming systems that harken back to al-Balkhi, or embrace other conventions altogether. 2. The Pagsian Turning roughly corresponds to the periods of time humans have identified with the labels: Eemian, Sangamonian, Ipswichian, Mikulin, Kaydaky, Valdivia, Riss-Würm, and Marine Isotope Stage 5(d-e). It also roughly coincides with the Abbassia Pluvial period in Northern Africa. The onset of this turning roughly corresponds to the climate shift identified as Termination II (T-II) by Quaternary geologists, oceanographers, and paleoclimatologists, marking the end of Marine Isotope Stage 6 and the onset of Marine Isotope Stage 5. Scientists will place the exact date of this shift anywhere between 130,000 BP and 122,000 BP, depending on whether they are basing their estimate on marine isotope records, changes in terrestrial vegetation, pollen density measurements, ice core datasets, or other factors. The onset of the Pagsian turning is based on when the people of the world began to experience significant long-term stability in their weather cycles and the natural ecosystems of their environments. For the same reason, despite a brief cold surge in Europe between 123,820 and 122,000 BP, associated with the MIS 5d/5e boundary, the shift from the Pagsian Turning to the Recosian Turning does not happen until the later temperature downturn that is associated with the MIS 5c/5d boundary and coincides with the Dakhleh Impact. 3. The extent to which an extended barrage of meteor impacts could disrupt world atmospheric patterns is a matter of debate. Analysis of airburst and impact glass residue suggests that the fireballs created by low-angle meteor strikes could create firestorms from superheated gas that exceed the actual volume of the explosive fireball by more than an order of magnitude (e.g. Osinski, Kieniewicz, et al., 2008). Simulation models show that the timing of such an event could play a critical role in even world-wide climatological shifts if it coincides with other periodic variations such as solar radiation variability or the earth's rotation or axial tilt. 4. Pagsian cultures were simple and largely constrained by the necessities of the environment. This imposed a certain type of uniformity of certain practices. Skills that humans needed to survive in Sahel also usually worked in Kaapvaal; the lifestyle of denisova in Indus did not need to differ dramatically from the lifestyle of denisova in Chang Jiang Pingyuan; and the tools required to meet the day-to-day needs of neanders did not depend on whether those neanders were in Iberia or Ural. Even when clans could go for entire generations without coming into contact with other clans, these environmental constraints shaped behavior to impose some uniformity. This is why we are able to describe these "first cultures" in generalized terms. 5. For further discussion, see part 1 Language Origins in Appendix C: Climate, Culture, and Language. 6. The specific practices associated with things like mourning the dead or teaching hunting skills to young people varied a great deal across clans, because they are relatively arbitrary and the lack of interaction meant there was no opportunity for clans to share their specific practices with others. Thus, although we label these first cultures very broadly it would be incorrect to assume that every single Awari clan followed identical burial rites or constructed shelters in the same way, or that every Moustrian clan attached the same meaning to the symbols they would paint in ochre on their bodies and on the ground. Populations were so sparse that most clans were isolated for long periods of time, without any opportunity to share skills and practices with each other. As a result, these family groups exhibited more variety in many respects than we see in the world today. Anything that was not functionally limited by survival—decorations, rituals, folk stories, ways of honoring the dead, and so on—would often be completely distinctive and unique to each clan. These can be thought of as family traditions: not unique to individuals, but not shared broadly enough to fall into the category of culture. Another way of understanding this relationship is through the lens of Tversky’s (1977) contrast model of the psychological perception of similarity (see also Tversky & Gati, 1978; Kahneman & Tversky, 1972; Kahneman & Frederick, 2002). According to Tversky's model, people assess the similarity between any two things (including concepts, groups, or ideas) by evaluating how many of their features overlap, and how many do not overlap. One side effect of this is that things that are simpler will inherently be seen as more similar, because as your subconscious mind is going through the list of overlapping and non-overlapping features it will simply be unable to come up with as many nonoverlapping features as those things that are more complex, or that you know more about. The parallel here is that when a culture is defined by a relatively small number of shared characteristics, it is easier for that culture to persist unchanged over larger geographic areas and for longer periods of time. As interaction amoung groups becomes more frequent and cultures begin to include more and more shared practices and beliefs, these cultures are defined by more "features" and thus have more opportunity to identify significant changes over time or schisms between different populations.Turnings Index

Type Key