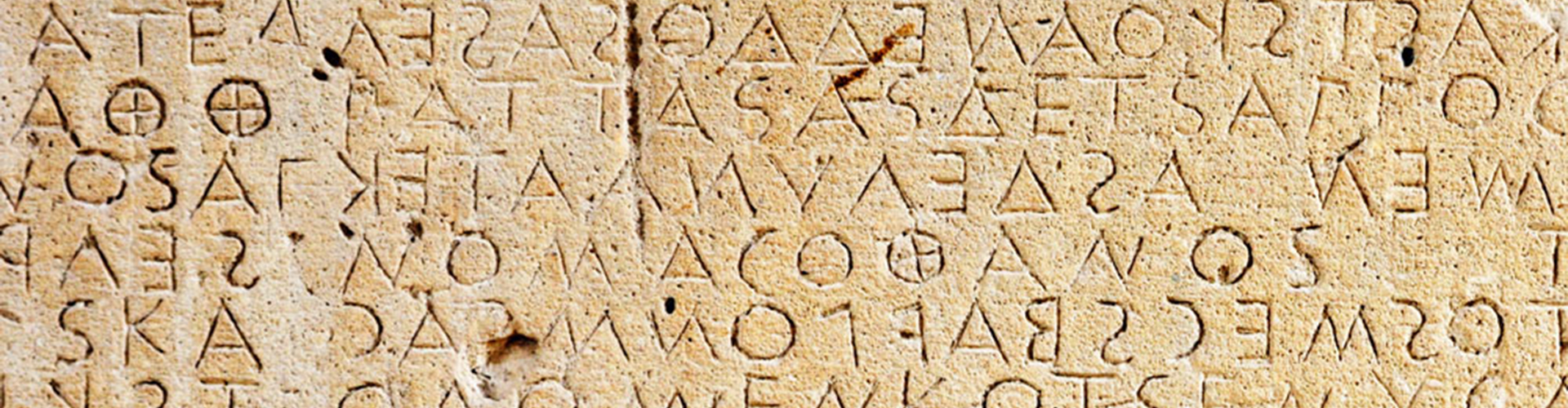

Aterian People (/ˈɑteriɑn/)

Aterian culture1 was the first culture of humans, emerging in Africa at the dawn of the Pagsian Turning and eventually disappearing by 40,150 BP.

Lifestyle

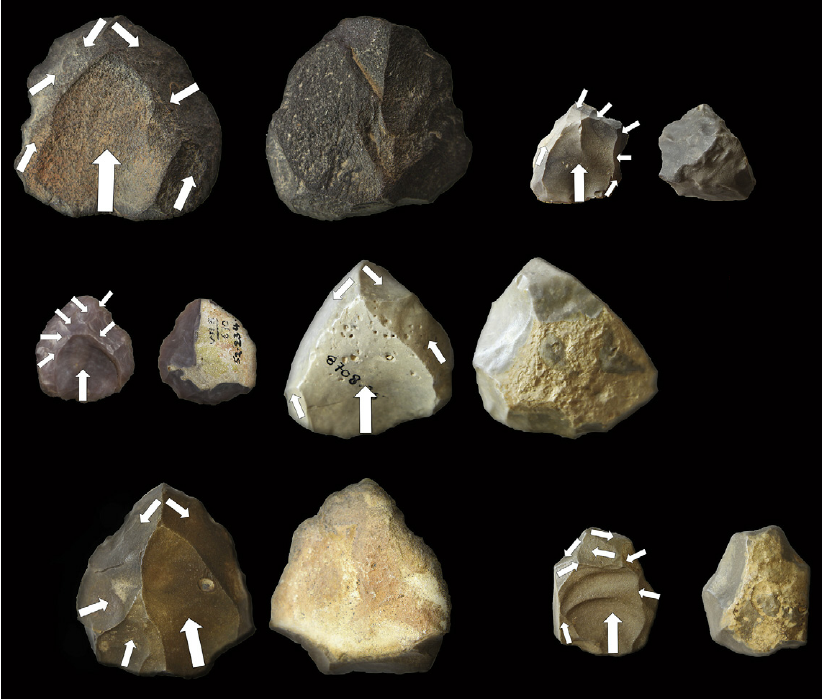

Aterians clustered in extended family clans, each composed of 50-100 people. These family groups were nomadic and isolated, rarely coming into contact with each other. They hunted antelope, buffalo, elephant, and rhinoceros using stone-tipped sticks, and when they were by lakes or the ocean they gathered clams and other shellfish along the shore. They painted their bodies with ochre and tinted mud, they decorated their bodies with sea shells, and they collected calcite crystals. Aterian clans used linguistic behavior to plan hunts and teach children how to make and use tools. But each clan had its own individual clan language, and storytelling was not an idea that they were familiar with. Even when life was easy and they lay out under the stars with bellies full of food, questions like "where did the universe come from?" or "why does the sun rise and fall?" simply didn't occur to them. The world was vast and alive and largely incomprehensible. Telling stories about why birds fly simply mattered less than planning the next hunt. This was a common Aterian mindset that persisted across millennia and across Turnings.Migrations

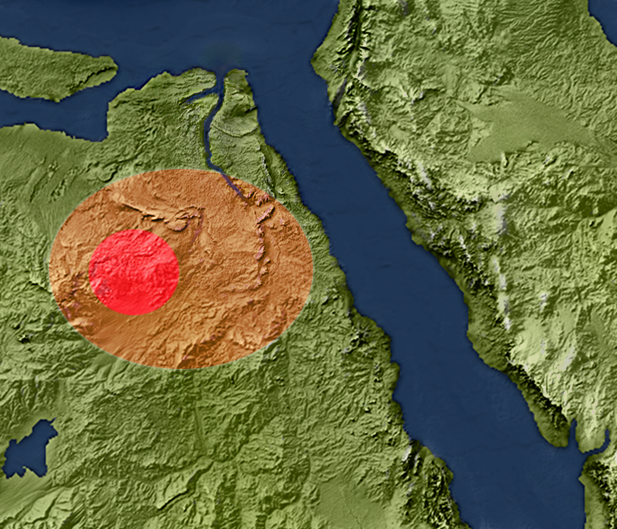

Because Aterian people usually camped near lakes, rivers, and springs, the north African droughts of 123,820 BP caused clans in Sahel to migrate eastward and collect by the coast. Soon Wadi Halfa emerged as a traditional meeting spot that clans would return to year after year, especially in the autumn. Unfortunately, the Dakhleh Impact at the end of the Pagsian Turning was so close to this landmark that it wiped out about a third of the human population. Aterians in northern Africa fled to the mountains or to coasts by the water, while those who hunted far to the south found themselves avoiding their traumatized neighbors and developing their own distinct Xhaaxhaanebee culture. The deteriorating climate of the Recosian and Ougrosian turnings led to the first mass migrations out of Africa, giving rise to Emiran culture in the Levant and Adivasi culture in Indus. The Tādhēskō and Pluvial Turning that followed caused Aterians to explore within Africa, giving rise to a number of African cultures including the Bayaka, Babongo, Mbuti, Ounjougou, and Dabban.Dissolution

After ten millennia of warm and comfortable climate during the Pluvial Turning, the largest mass migration of humans out of Africa began. Aterians swarmed northward, passing by the Emiran in the Levant and continuing on to found Bohunician culture in western Anadolu, Satsurblian culture in eastern Anadolu, and Ganj Par culture in Airyanem Vaejah. This hollowed out the population of Aterians remaining in Africa, threatening their way of life. The population decline combined with increased frequency of contact with other groups with more diverse ways of life eventually put enough social pressure on the remaining Aterian clans that they adapted and shifted their lifestyle, resulting in Aterian culture dying off and being replaced by Khormusan culture in a smooth and gradual transition that was complete by 40,150 BP.Migration Maps

Species

Key Attributes

nomadic hunting gathering stone-working shell carving

Founding

the beginning

Disbandment

40,150 BP

Diverged culture(s)

Homeland