Ougrosian Turning (/ˈɔːgɹəʊˌsiːən ˈtɜːnɪŋ/)

(73,110 BP - 64,560 BP)

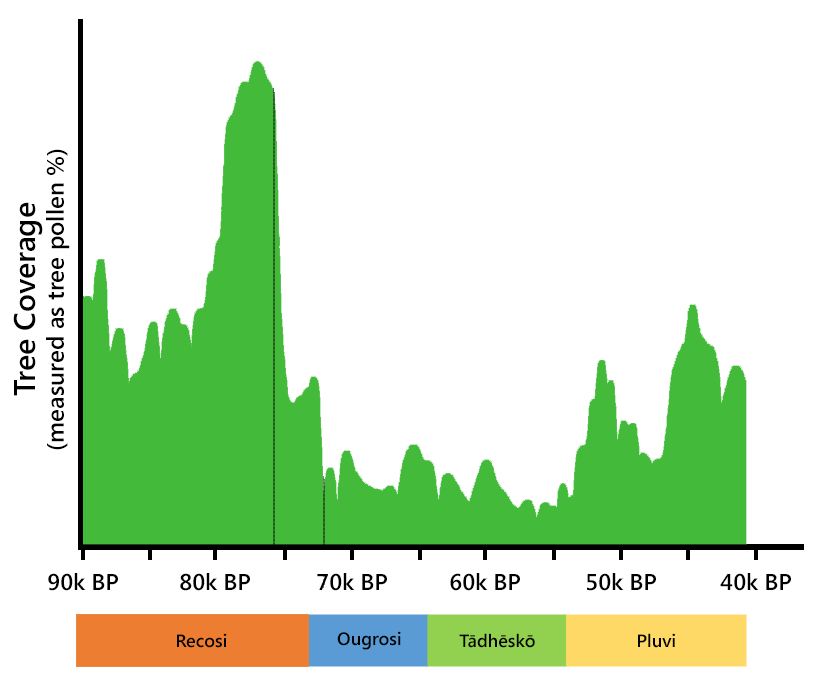

The Ougrosian Turning1 was a catastrophic global ice age that lasted just under nine thousand years.2

Climate and Ecology

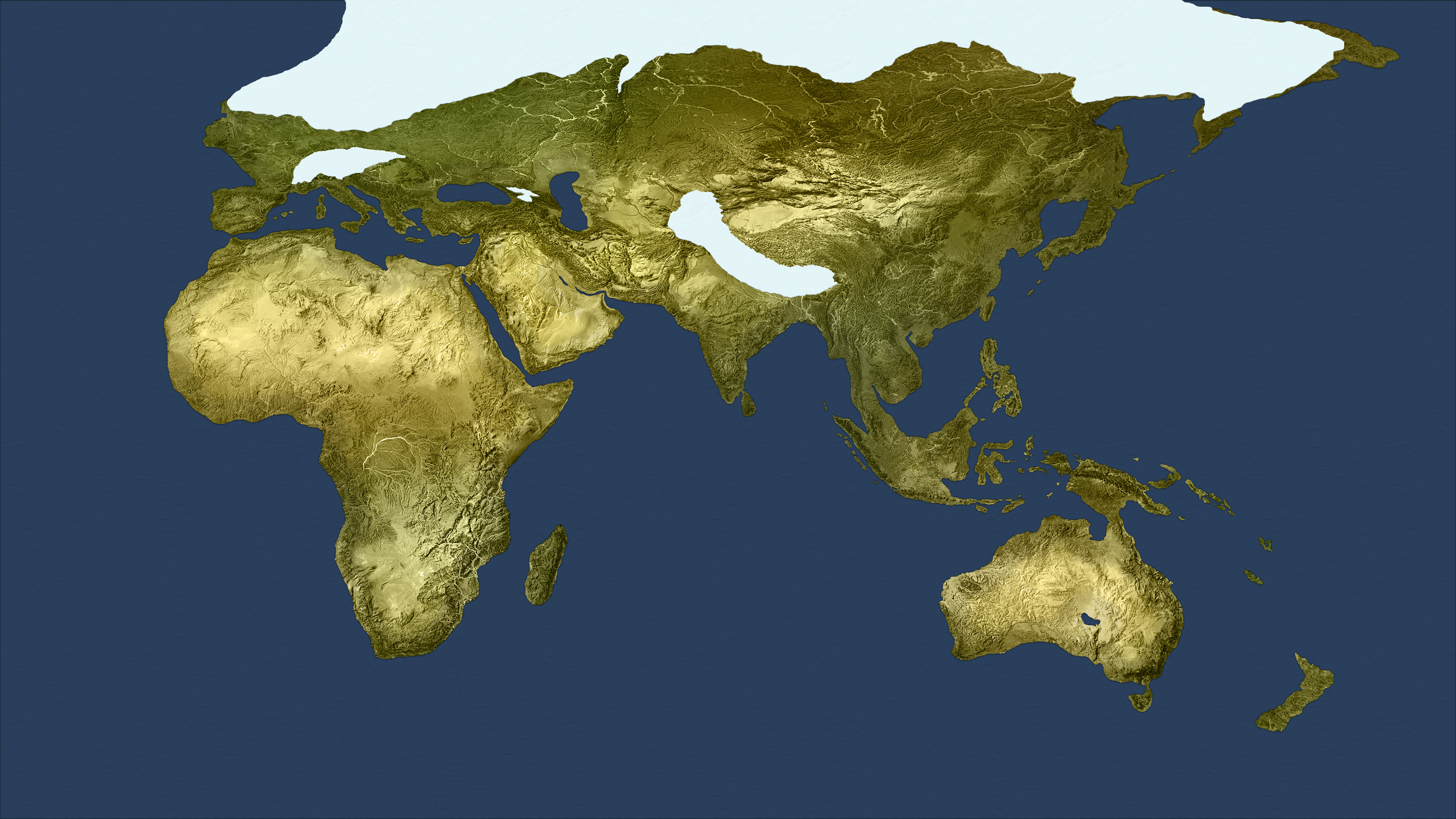

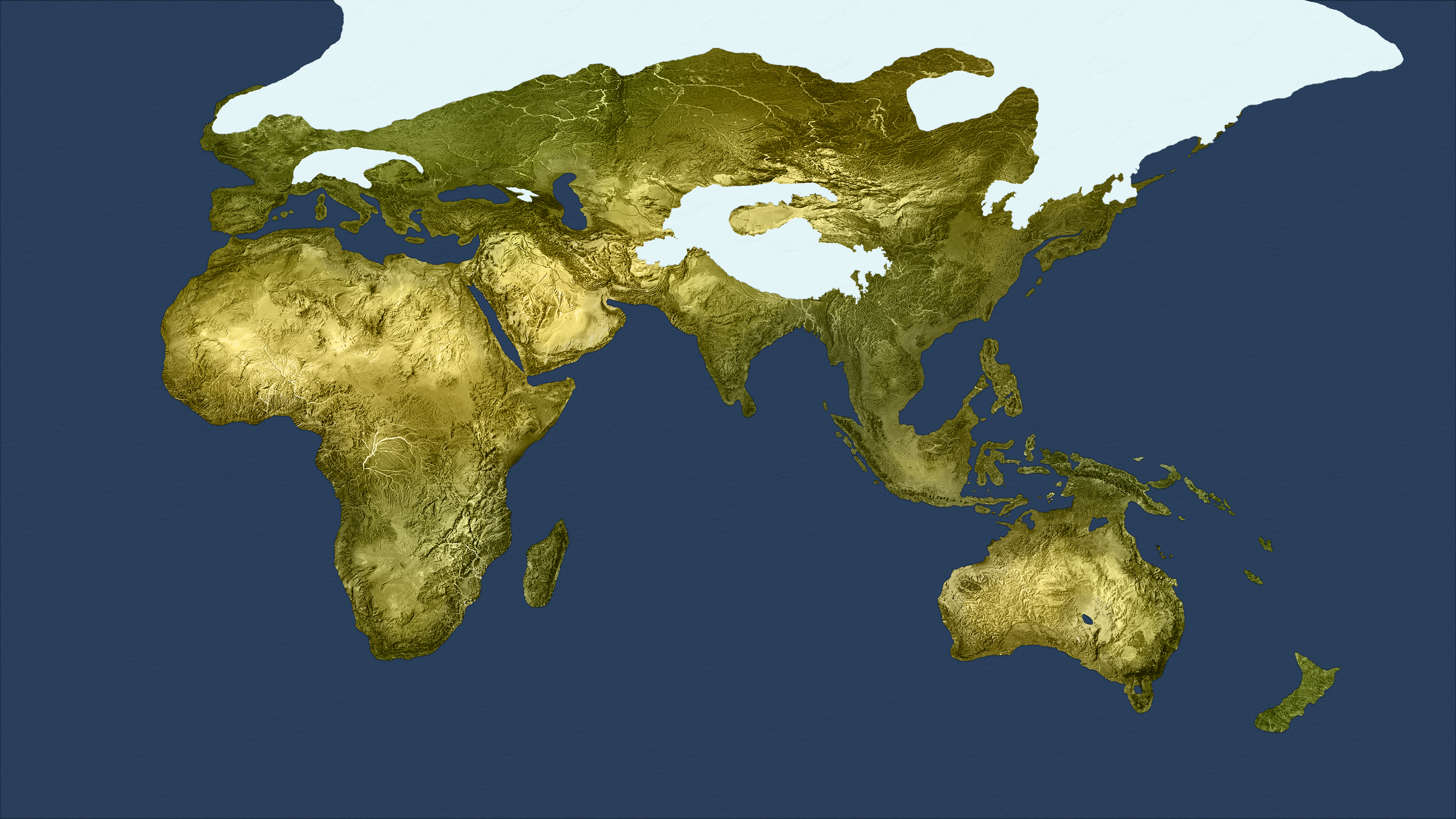

Following the Toba Eruption of 73,110 BP the world experienced a worldwide catastrophic drop in temperature. Glaciers engulfed Skáney, Avalonia, Sibir, Kolyma, and parts of Altai. Deserts grew to take over northern Sa'hra, the Sahel, Arabia, Zomia, and Sahul. Falling sea levels exposed Sunda so that it formed a continuous land mass with Zomia and Indus.Kasai Ecosystem Collapse (75,500 - 72,100 BP)

The process of ecological collapse in Kasai that had started in the previous turning continued and bottomed out in 72,100 BP. The land that once had been fertile tropical forest had been transformed into semi-airid steppe. Thousands of species had gone extinct, while larger predators migrated southward in search of food.Dessication of Nihonkai (73,000 - 68,000 BP)

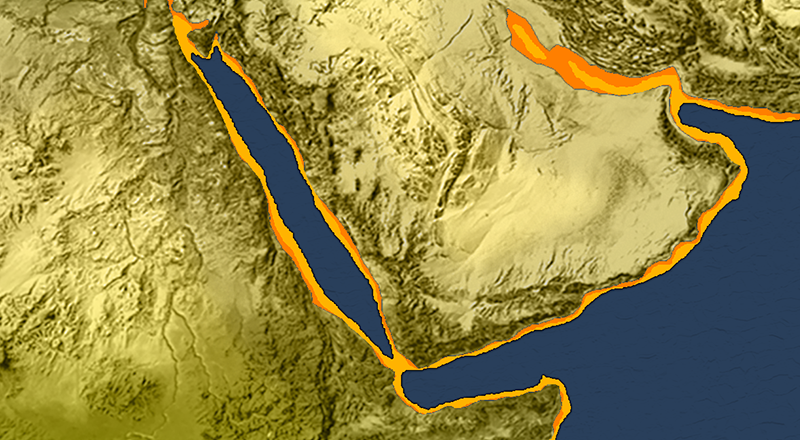

The Nihonkai Sea shrank and eventually disappeared in the first half of the turning. The low-lying field that emerged was fertile and became a refuge for wildlife that had been displaced by glaciers. In the aftermath of the Asosan eruption, it transformed into pristine wilderness.Formation of Lake Eruthraía (72,860 BP)

A land bridge formed cutting the Eruthraían Sea off from the Bharata Sea, transforming it into a brackish inland lake: Lake Eruthraía. As deserts in northern Africa grew, the marine life in this lake became an important source of food for humans that travelled up and down its shore.Cultures

This ice age was devastating for all of the people of the world, with most clans finding shelter and simply surviving any way they could. Radical changes to ecosystems caused by the cold and airidity led to massive population reductions among humans, denisova, and neanders alike.Emergences

Moustrian neanders continued to flee the advancing glaciers, with some migrating to establish Teshik-Tash culture in Airyanem Vaejah and Hušnjakovo culture in Cycladia while the rest simply sheltered in small refuges in the narrow strip of land between the northern glaciers and the ice caps that descended the mountains of Alpidia. Aterian humans living along the shore of Lake Eruthraía discovered the new land bridge that provided access to Arabia, and several ambitious explorers followed the shoreline eastward until they reached Indus, where they established Esea culture.3Encounters

The mixed human-neander Emiran culture thrived during this turning, despite the environmental challenges.4Extinctions

The influx of new large preditors from Kasai to Namaqua-Natal disrupted the Stilbaai people, who tried to adapt but ultimately died out.5 The Chagyrskaya neanders died off as a consequence of isolation and inbreeding. They had established their society with only 32 individuals in 101,000 BP when they reached Kasang Khim. They relied on severe inbreeding to survive, which led to much shorter lifespans within a few generations. Their population shrank and eventually was not able to sustain themselves. They died out completely by 66,100 BP.Culture Map

This map does not represent all movements by all individuals or clans, but only shows a selection of some important cultural shifts for the purposes of illustration.Turning Type

Ice Age

Preceded By

Harbinger Event

The Toba Eruption

Start Year

73,110 BP

End Year

64,560 BP

Succeeded By

Footnotes

1. The label Ougrosian was introduced by Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie in 75 BP, and like most of the pre-Srīgosian turnings the name is unattested in writing contemporary to the turning and was purely constructed by Mackenzie. Because Mackenzie was unable to find attestations of a name for this turning, he simply applied the Yék root for the idea of cold. This followed a common practice of people in Europe at the time, and was part of the trend that began with Ficino of trying to harmonize all of the turning names to be based on roots in the Yék language family. (For further discussion, see Appendix A.) 2. The Ougrosian Turning corresponds roughly to the ice age geologists and paleoarcheologists refer to as (Major) Glacial Sage 4 or the Weichselian Glaciation, and is included within the periods referred to by these labels: Würm glaciation, Devensian glaciation, Midlandian glaciation, and Wisconsin glaciation. Because this turning is followed by a Tādhēskō, which by definition is gradual and is not signaled by a harbinger event, placing the exact end date is difficult and, to a certain degree, arbitrary. We have chosen to tie the end of this turning to the geological Stage 3/4 boundary (see, e.g., Martinson et al., 1987; Imbrie et al., 1984). 3. This emergence is what archeologists commonly refer to as the "southern dispersal" when talking about human migrations out of Africa. Rather than having a single cause, the southern route migration was enabled by a sequence of external environmental factors: the Dakleh impact forced humans to the coast; ongoing drought conditions that led them to turn to clams, seaweed, and other marine life in the lake for their diet; this positioned them perfectly when the land bridge was created by falling sea levels. Although narrative and mythological evidence for this migration has been a part of turning scholarship for at least two centuries, it has been corroborated by recent scientific data, such as the evidence that the southern disperal can be traced back to a relatively small clan of original migrants (see, e.g., Culotta, E. and Gibbons, A., 2016). 4. The success of Emiran culture was both environmental and cultural. The Levant was cool but not frigid, and its proximity to the coast meant that they did not endure the airid conditions that were taking over northern Africa. The difficulty the humans and neanders in the region endured drew them closer together, inducing them to cooperate and learn from each other. The earliest fragments of folk stories and myths from this culture have also been corroborated by recent scientific studies using genetic analysis and carbon-14 dating (see, e.g., Boaretto, E., et al., 2021) that clearly show evidence that humans and neanders both interbred and mixed culturally. 5. One of the most interesting stories of cultural change can be found in the development of the peaceful and innovative artist collective in Blombos cave, their abandoment of the cave as a consequence of large predators that entered the region because they were fleeing the collapsing ecosystems in Damara, and the wave of innovation followed by collapse that resulted from them being forced from their home. This is one of the rare situations where very specific innovative tools were invented, used for a period of time, and then abandoned (for discussions see Lombard & Parsons, 2011; Way, de la Peña, et al., 2022).Turnings Index

Type Key