This article is an introduction to the concept of a "turning" and a brief history of the development of the theory of turnings as it has evolved over the last five centuries. Independent researchers who are new to this area of scholarship may find themselves quickly overwhelmed by the sheer mass of intricate references, connections, and speculative hypotheses that make up the field. While research into the turnings is not scientific

per se, it draws upon a web of interconnected data, observations, texts, and theoretical frameworks that integrates modern scientific data and observation from geology, paleoclimatology, and cultural anthropology with observational research from fields such as comparative mythology, linguistic anthropology, semiotics, and cosmogeny. The purpose of this article is to provide a starting point and overall framework to help researchers who are just getting started.

Part 1: Core Concepts

It is an ancient and widespread idea that the timeline of human experience can be segmented into intervals having distinct environmental and cultural attributes. The Hellenic poet Hesiod (c. 2,700 BP) identified five

génei hústeros: a Golden Age, a Silver Age, a Bronze Age, and an Iron Age.

1,2 Augustine of Hippo wrote about the six ages of the world (

sex aetates mundi) in

De catechizandis rudibus (c. 1,547 BP). The Andronovo people (c. 3,800 BP) told stories of a cycle of four

yeug (roughly "yokes of time") that repeated over history. This idea was later incorporated into Vedic texts as

युग ("yuga"). The Śramaṇa people (c. 3,200 BP) spoke of four

kalpa that made up the larger

mahā kalpa cycle.

The word

turning has emerged as the most common

term de arte in the paleomythologist and estoteric circles engaged in the area of research we are discussing here. However, you should keep in mind that not all writing that can be considered source material for the "study of the turnings" use the word "turning" to express this idea, even in English language texts.

3 You will often have to discover for yourself whether a particular text is expressing a truth about the turnings based on the context and connections it has with other work in the field.

Universes, Aeons, and Ages

One of the earliest attempts to systematically document and synthesize empirical and mythological evidence of the turnings appears in an unpublished manuscript by Marsilio Ficino titled

De universi libri antiquorum ("Books of the Universes of the Ancients"), written during the period 1479-1485 CE

4. In that work, Ficino describes a tablet that came into his possession from his travels to Masovia, the origins of which he traced to Thracia.

Although the tablet has been lost, Ficino carefully rendered the inscriptions on the tablet in his manuscript, allowing us to identify the language of the tablet as U̯reku̯ somewhat awkwardly transcribed using the Sungraphḗ Caphtor writing system, which places the date of the inscriptions fairly precisely around 3,750 BP.

5 Ficino successfully deciphered the text on the tablet as a collection of aphorisms from Thracia, including a symbol cluster that reads:

ku̯elə nĕzgu̯es, óynos wértís cejwonti

This translates roughly as, "The wheel does not stop (terminate), [but] we live in a single (unique) turn (rotation)." Although the language of the tablet is clearly U̯reku̯, the saying expressed by the aphorism is likely much older. The first block of inscriptions on the tablet describes its contents as "ancient wisdom" (

antweid) passed down orally through generations, and is most likely Kundan or even Sandarnan in origin. Ficino placed a lot of importance on that aphorism, and specifically on the term

óyno wér ("unique turn"), from which he inferred the etymological connection: óynos worssos ➤ ūnus versus ➤ universus.

He makes use of this etymological connection for the title of his own manuscript

De universi libri antiquorum, and again when he translated the manuscript

Kitāb tanawub al‐duhur (كتاب دورات الدهور) by Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi in 1482 CE. That manuscript was written between 870 CE and 886 CE, and was only discovered after al-Balkhi's death. Ficino translated the title of that work as

The book of the many universes of eternity. This translation illustrates Ficino's preexisting bias toward associating the word "universe" with concepts of rotation or turning, since a more literal translation of that title would have been

The book of rotations of the ages.

Cyclical Time

Unfortunately, the word "universe" was judged to be somewhat lacking in the centuries that followed, Ficino's clever etymological analysis notwithstanding. In modern English-speaking cultures the word "universe" is most strongly associated with a scientific understanding of the cosmos, linked to ideas such as forces, matter, energy, and spacetime. The word "age" was favored for a period of time, but in today's culture has evolved into a very mundane way to classify intervals of time, such as a stage of cultural development ("Industrial Age") or a period in pop-culture history ("the golden age of science fiction"). The key flaw in all of these terms is that they do not capture the idea of the cyclical nature of time that is expressed by the original U̯reku̯ phrase.

The beauty of the phrase "The wheel does not stop, but we live in a unique turn" is that it acknowledges the tension between two ways we can experience our phenomenological world: on the one hand, we have a day-to-day experience of navigating a world that often feels fixed and immutable; on the other hand, we recognize that in our lifetimes we experience only a single snapshot of a universe that is unimaginably vast and constantly changing in a dynamic cycle. The U̯reku̯ aphorism uses the metaphor of a turning wheel to draw our attention to this dynamic cycle. Because of this, the label "turning" has become the

term de arte for this concept within English-speaking paleomythologist and estoteric circles.

Part 2: Identification and synthesis

The

Kitāb tanawub al‐duhur ("The book of the many universes of eternity"), referenced earlier, by Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi is one of the earliest known attempts to aggregate and synthesize ancient sources in order to develop a fuller understanding of the history of our world, and of ourselves as a sentient species. Al-Balkhi was an astronomer and astrologer whose philosophical interests became more diverse and eccentric as he got older.

6 In this text, Al-Balkhi set out to name and describe past turnings of the world by careful comparison and synthesis of ancient sources. Several of the names that we currently use for turnings can be traced back to al-Balkhi.

Meghalaian Turning

One section of

Kitāb tanawub al‐duhur that was recovered and translated by Ficino describes a set of mystical inscriptions on clay tablets that had been found in the ruins of Takṣaśilā, written in the Saṃskṛtá language using what appears to be an archaic form of the Dhamma Lipi orthography. The Takṣaśilā Tablets describe the journey of the Andronovo people as they fled political upheavel in Europe.

According to al-Balkhi's translation and interpretation, the tablets describe travellers who were making a journey to escape increasing unrest and conflict, only to see

/mɐj.ɡʱɐ́/ ("clouds")

/ɑːləjə/ ("of dirt" or "of grime") hanging over the land they had just left. The scribe who recorded the story on the Takṣaśilā Tablets interpreted the "clouds of grime" seen by his ancestors as harbingers of the new era of humankind, saying that it marked the beginning of the age of

/meɪˈɡʱɐ́ːləjən/, written in Dhamma Lipi as

मेघालय.

With the benefits of modern science, we now know exactly what those travellers saw. They were seeing ash, soot, and dust thrown into the atmosphere by the Umm al Binn Meteor Impact in Birit Narim in the year 4,213 BP. Al-Balkhi was absolutely correct that he was reading a story from a critical moment marked the end of a previous golden age, and the start of the age in which we now live. With the benefits of modern science, we can now can attach an exact year to the start of this Meghalaian Turning, as well.

Srigosian Turning

Not all turnings have names with such a straightforward history. For example, al-Balkhi notes in his book that there are multiple ancient sources that refer to a "primeval frost" era, and takes care to tabulate and cross-reference descriptions from people from different cultures and regions. According to al-Balkhi, the very earliest source was a tablet found in the mountains outside of Çermo referring to a time when all the world was dark and covered in frost. That tablet, according to al-Balkhi, uses the term

kuḷutti kala, a name that suggests the source was written by Yarmukians in an early form of the Kenaʿani Dabar writing system. Because al-Balkhi was very interested in preserving the "original" names of things, the name he adopts for this ice age is Kuḷutti Kala.

However, when Ficino later was translating the works of many ancient scholars, including the book by al-Balkhi, he tried to "harmonize" the names of the turnings under a single language system. Ficino therefore labels that ice age

srīgosi, which is a direct calcque of the Karā'um phrase

kuḷutti kala into Yék. Ficino goes on to try to justify his label based on some Acheyawan mythological texts that refer to a

srīgosi era; this rationalization is somewhat post-hoc, however, especially since the Acheyawan myths would necessarily have come several millennia after the Mureybetian inscription.

Ficino was not alone in this linguistic prejudice. We see a strong bias in canonical names in the literature being related to the yék language family, and specifically the descendents of that language in Cycladia and Thracia and Variscides. When the compiled knowledge of the turnings was passed down, added to, and elaborated on by John Dee, Kenneth Mackenzie (possibly through Alphonse Louis Constant, a.k.a. Eliphas Levi), and then Aleister Crowley, each of these later European scholars retained and perpetuated this bias in the names used within turnings scholarship.

Pagsian Turning

Another example of this bias can be seen in the name

Pagsian, which was introduced by Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie in 75 BP as an anglicization of PA-KA-SI-A, a direct phonetic transcription of the Kuraną word that appears on Tablet EN-8239X. Although unknown to Mackenzie at the time, later researchers have determined the tablet was created by the Acheyawan civilization some time around 3,630 BP, which accounts for the obvious connection to the Yék root

pak (fasten, bind, hold together) which also shows up in the etymology: pak ➤ pax ➤ pais ➤ peace.

This turning was added late to the ensemble of recognized turnings, exactly because it is so ancient that finding the trail of stories and and references to it is difficult. Nonetheless, the name

Pagsian follows in the tradition established from Ficino on of "normalizing" the names of turnings into a language connected to Yék and its descendents.

In 72 BP, Henry Steel Olcott proposed an alternate naming scheme for all of the turnings that was based on Pūraw linguistic reconstructions. Olcott proposed this alternative naming scheme overtly as a response to the habit of "normalizing" turning names around yék roots, which he saw as an attempt to erase scholarship and impact from Levantine and far eastern cultures. In the naming system proposed by Henry Olcott, the first turning of the world is called

En Nesha'alm. This is only one example of several attempts in recent scholarship to develop naming systems that harken back to al-Balkhi, or embrace other conventions altogether.

Although al-Balkhi was groundbreaking in his assembling and synthesizing archeomythological data about turnings, he saw himself purely as an archivist rather than a theoretician: he identified and labelled turnings, but made no attempt to come up with a systematic taxonomy or a theoretical framework for them. That work began with Ficino, and was developed further by other European and Asian scholars in the centuries immedialy before and after the year 0 BP.

Part 3: Theoretical frameworks

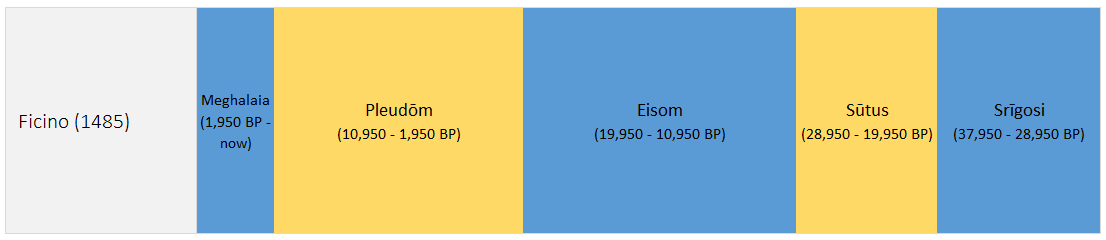

Ficino's Taxonomy

Ficino was the first to put together a systematic taxonomy of turnings that characterized them in relation to one another. He created a two-fold typology in which turnings alternated between

prunsō (freezing) and

tādhēskō (melting). Drawing heavily on the descriptions provided by al-Balkhi, and finding parallels to other ancient sources he encountered in his travels, Ficino firmly established that humans had experienced at least two

prunsō ages in the distant past.

Although he was able to ascertain some aspects of the

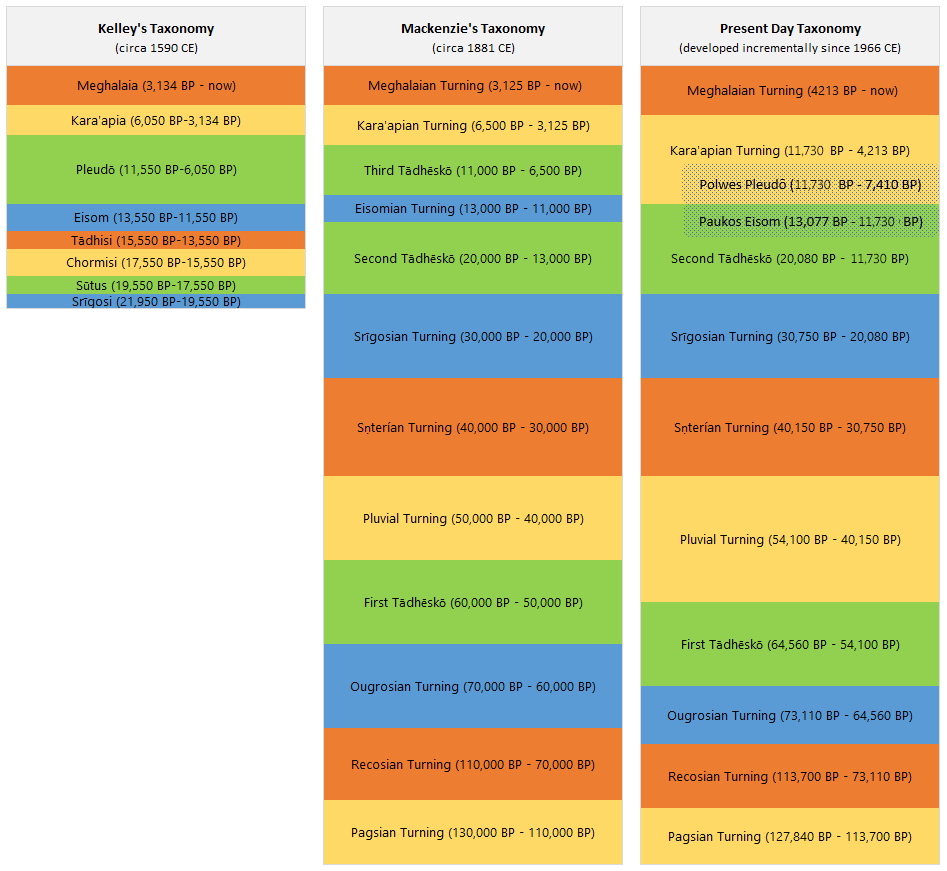

character of these ancient freezing ages, and the melting ages between them, he did not have enough information to deduce when these ages began and ended. For this, he resorted to the familiar territory of astronomy and numerology, and finding synthesis with other cosmological and philosophical patterns that governed the universe. For example, Ficino made heavy use of triads in his own magic system and cosmological work, and commonly used the number nine: a trinity of trinities. He therefore suggested that a "trinity of trinities" of millennia (9,000 years) were a sensible and conceptually pleasing unit of time for the length of turnings. He also used the ACN calendarization, which counted years from the "zero point" of the birth of Yshua the Nazarene. With these assumptions, he was able to reconstruct a set of five turnings that had their boundaries at the years the years 1AD, 9000 ACN, 18000 ACN, 27000 ACN, and so on. (For consistency, these dates have been converted in the diagrams below to the BP calendarization used throughout this manuscript.)

The present day is on the far left, with time going backward as you move to the right. Blue bands are freezing (prunsō), yellow bands are melting (tādhēskō).

Ficino recognized two obvious flaws with his framework. First, this framework suggests that the current turning (Meghalaia) should be a freezing time (prunsō), a matter that is not consistent with his own or anyone else's observations. Second, Ficino's choice to represent the durations of turnings with idealize measurements, this system does not easily align with several important historical events and periods.

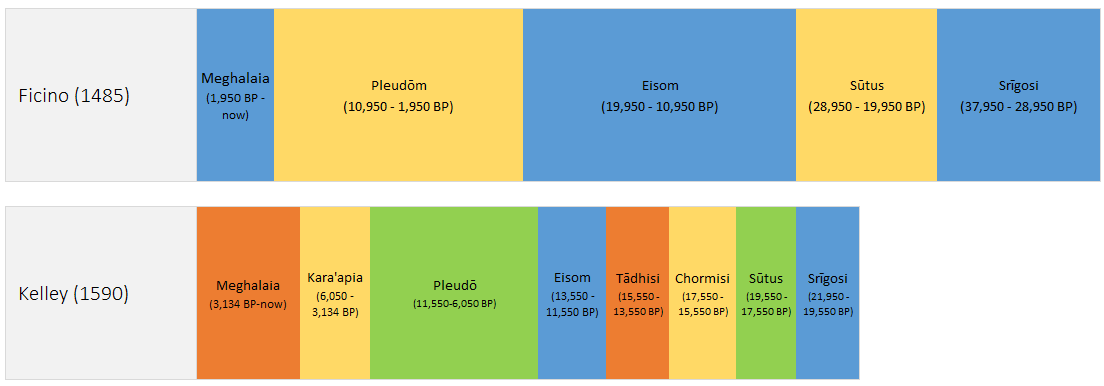

Kelley's Taxonomy

John Dee was an avid scholar of the translation work and scholarship of Marsilio Ficino. Dee had several well-known writings and translations of Ficino in his library, including Ficino's Latin translation of the Picatrix grimoire. Over the years he had built up an extensive secret library of work by both Marsilio Ficino and his student Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. These texts represented some of the earliest attempts to synthesize Jewish mythology, such as Kabbalah, into western esotericism. John Dee's secret library also contained Ficino's writing on the turnings, as well as new research by both John Dee and Edward Kelley to add to the new and emerging field of turnings scholarship.

Most of what can be verified as having been part of John Dee's secret library was clearly written and annotated by Edward Kelley, who was more enthusiastic about the intellectual endeavor than his mentor John Dee. As a result, Edward Kelley is the first confirmed source that we have for the four-fold cyclical typology of turnings: Golden Age, Decline, Ice Age, and Recovery. This was an important innovation in thought that we still use today.

7

The present day is on the far left, with time going backward as you move to the right. Ice Ages are blue, recoveries are green, Golden Ages are yellow, declines are orange.

Kelley's taxonomy made several important advancements over Ficino's initial work. Firstly, John Dee had access to more historical artifacts from Arica, Asia, and the Levant than Ficino ever did, which in turn gave Kelley resources that allowed him to do a better job of tying transitions between turnings to specific dates. For example, he calculated the start of Pleudō based on the work of Plato in Timaeus (22) and in Critias (111-112), which described the "great deluge of all" happening 9,000 years before the time of Solon, who was a notable political figure around the year 2,550 BP. The start of the golden age that followed, Kara'apia, was assigned to the date of the mythological founding of Egypt and creation of the Emerald Tablets of Thoth. For the end of that golden age and beginning of the current age of decline, Kelley chose the year that Hesiod declared to be the "end of the heroic age," based on the end of the Trojan war.

The earlier turnings, unfortunately, did not have much by way of historical or mythological records or stories on which to base things. For these turnings, Kelley simply fell back on approximating each turning as roughly two millennia. This may seem like a fairly short interval to use--much shorter than Ficino's 9,000 years, for example--but Kelley was also trapped by being unwilling to loosen his commitment to the fourfold cycle that he proposed. He had been given strong reconstructed evidence for the two ice ages, from Ficino, as well as some evidence based on cultural timelines and the believed dates of the tablets and manuscripts he drew on for analysis. His research suggested strong evidence for an ice age ending in roughly 11,000 BP and another one before that ending in roughly 20,000 BP. Having committed himself to his fourfold cycle, that did not leave very much time to get through three entire turnings between the two ice ages.

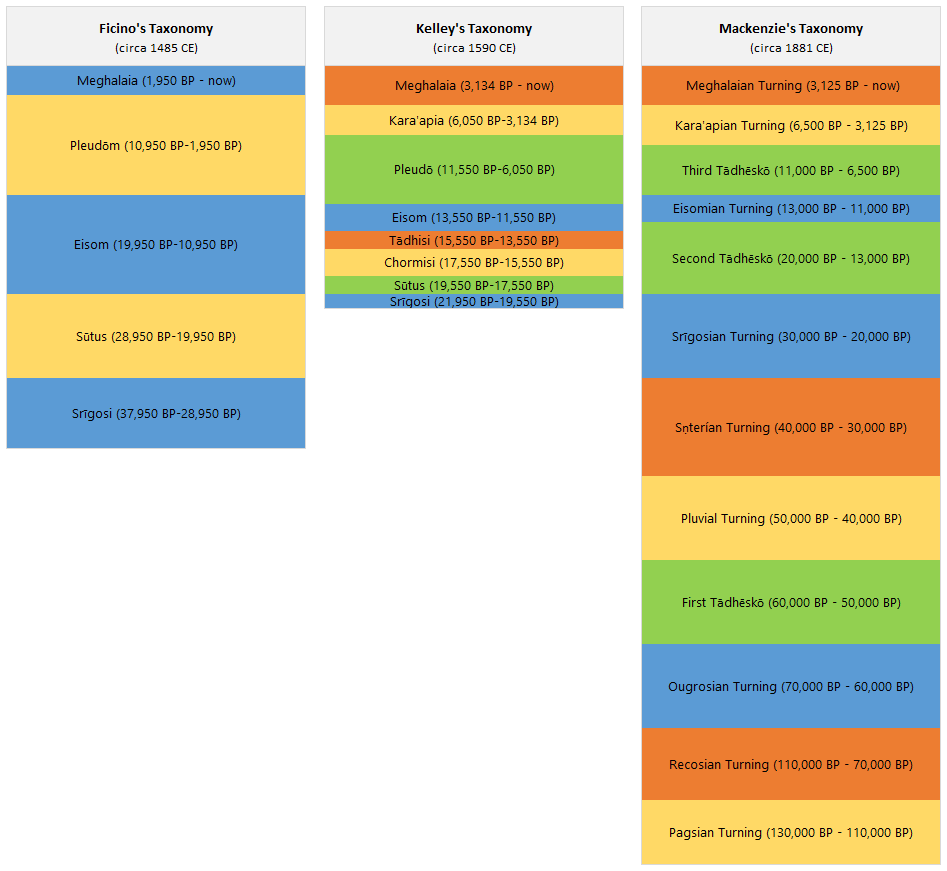

Mackenzie's Taxonomy

Research and scholarship related to the turnings was passed down primarily through occult and esoteric circles. All of this work would have been viewed as blasphemous during the height of the witch trial panic in Europe, but was naturally of interest to scholars interested in Hermetism and lost ancient knowledge. The growing scholarship associated with the turnings was passed down from Edward Kelley to figures such as Alphonse Louis Constant (Éliphas Lévi) and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers.

Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie travelled to central Europe in 89 BP to meet with Éliphas Lévi, and during that meeting was entrusted with a number of documents and archaic artifacts that had been protected within esoteric circles for centuries, handed down since Edward Kelley and Marsilio Ficino. Mackenzie founded the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia with Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers only a few years after that. Through that society, and later the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, knowledge of research into the turnings was passed on to key intellectual figures such as Aleister Crowley and William Butler Yeats. The Secret Societies they founded provided a perfect system and set of material resources to ensure that not only the knowledge was preserved, but also the ancient tablets, scrolls, and documents that made up much of the corpus of reference material for the study of the turnings.

During this time, the natural sciences were also making great strides, with biologists and geologists investigating fossils and biological residue left in the layered basins at the bottom of lakes and oceans, as well as some of the first analyses of ice cores drilled from places such as antarctica. This was the first time geological data was able to establish that the fourfold cycle of turnings went much further back than had previously been contemplated. Mackenzie was able to integrate existing turnings scholarship with important new discoveries in biology, geology and archeology, to produce a new taxonomy of turnings that went further back in time than any previous attempts.

Although Mackenzie was able to update and improve some of the boundary dates for several turnings, there were still limits to the kind of data he had available. This was before the invention of carbon dating, so it was almost impossible to get reliable scientific dates for ancient artifacts. Instead, Mackenzie pieced together biological data and found connections with the stories being told in mythological records, and reconstructed a timeline based on the best available knowledge at the time.

Mackenzie's taxonomy had two controversial features. First, it did not adhere strictly to the four-fold sequence for turnings: in an effort to synchronize his timeline with the best scientific evidence available, his framework had the Eisomian and Srīgosian ice ages alternating with only Tādhēskōs between them. This was viewed as controversial primarily because he was not able to offer any kind of rationale for

why the cycle would have broken down during that period in time. Second, the turning he identified as

Tādhēskō III was very unusual for a turning of that type: rather than a gradual and pleasant improving of conditions, this turning was one of upheaval because the warming was giving rise to violent floods that forced conflict and migrations.

The Present Era

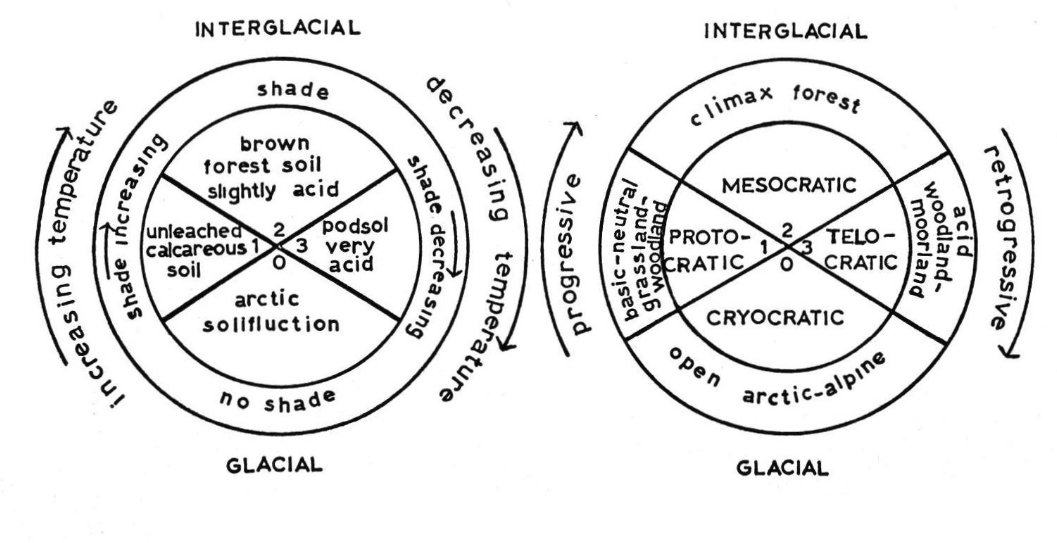

In the final decades before the present era, scientific advancements continued to proceed at a dramatic pace. Carbon dating was invented around 1 BP, and climatologists were developing their own classifications for long-term changes in the earth's climate. Unsurprisingly, these scientific classification schemes had a natural synchrony with the four-fold typology of the turnings.

During this period, turnings scholarship was primarily concerned with finding alignments between scientific fields of research in geology, ecology, and climate, on the one hand, and the already-identified cultural patterns and systems of movement and mythology, on the other. Mackenzie's taxonomy provided an excellent framework for this, allowing researchers to take the names and order of the turnings as a given and focus instead on figuring out what numbers to assign to the start and end of each turning.

There was one major theoretical upheaval during this time. It came about as a consequence of research that began in 46 BP. Ecological researchers Hartz and Mithers were comparing fossils and deposits in clay beds in Denmark to other data from around the world, and discovered that there was some kind of fast, dramatic shift around 13,000 years ago that abruptly tanked the temperatures in Europe, but that was almost completely isolated to that region. Geological and ecological research from around the globe established that the world had been going through an overall warming trend prior to that point: this was the turning Mackenzie identified as Tādhēskō II. In the decades following the initial discovery by Hartz and Mithers, it became clear that the reversal back to ice age conditions was

not worldwide: Europe descended into frigid ice age conditions for a millenium or so, after which everything rebounded.

8

That brief, sudden, localized dip in temperature has come to be known as the Younger Dryas in scientific circles, and corresponds roughly with what Mackenzie identified as

The Eisomian Turning. Moreover, the sudden reveral of the lopsided, Europe-biased ice age created some extreme anomalies in the millennia that followed. Unlike a standard Tādhēskō, the European climate recovery after the localized ice age led to hyper-rapid melting as the climate in Europe rebounded, seemingly eager to "catch up" to the rest of the world that was already experiencing a warm, humid golden age. As a result, this period of recovery after

Paukos Eisom ("little ice") became known as

Polwes Pleudō ("many floods"). All across Europe, the normal waterways couldn't handle all of the meltwater that was being dumped into them so rapidly, resulting in a quick sequence of disasterous floods across the continent.

This led to heated debates within the community of paleomythologists and other turnings scholars as to whether

Paukos Eisom and

Polwes Pleudō should even be considered turnings at all. Outside of Europe, the period of time during

Paukos Eisom was simply a continuation of the recovery, and while

Polwes Pleudō was happening in Europe, the rest of the world had already entered the golden age that was to follow. These two epochs, while certainly culturally significant in Europe, were definitively

not global in scope. Moreover, accomodating them as specialized "local abberations" allowed for an elegant solution for preserving the four-fold cycle. This is the current representation of the taxonomy of turnings that is accepted by most researchers today.

Should

Paukos Eisom and

Polwes Pleudō be considered turnings? The matter is still under debate as of the writing of this article. For the purposes of the

The Book of Turnings, we have chosen to treat them as turnings, giving them their own chapters and numbering them as the ninth and tenth turnings of the world. We also make note of the ambiguity where it is convenient and important to do so. Science is ever-evolving and sometimes messy, so perhaps it is appropriate to expect some degree of ambiguity as the scholarship of the turnings pursues alignment with relevant archeological, geological, and climatological research.

![Schematic of relationships among the three species of people. [Adapted from Dolgova , 2018] Schematic of relationships among the three species of people. [Adapted from Dolgova , 2018]](/uploads/images/390cff69d26d1f29e063c56eedbbe6fe.jpg)