Language and culture continuously coevolve in response to climate changes, conflicts, and other external stressors. This article examines two case studies that illustrate the complex relationship among climate change, cultural conflict, and the development of shared human languages.

Language Origins

At the dawn of the Pagsian Turning, more than 125,000 years ago, denisova, neanders, and humans all hunted and foraged for food in clans of extended family members. They had much in common, in part due to their biological similarities as cousin-species evolved from a common ancestor. All three manufactured tools and weapons, and passed their knowledge of hunting and tool manufacture down from one generation to the next. They created decorative art and ornaments, and enacted rituals to honor their dead. They planned hunting expeditions, and they gathered fruits and berries, dug for tubors and legumes, and scavanged plants, roots, and marine life. All three species passed knowledge from one generation to the next, creating a constellation of interconnected persistent learned traits that we refer to as

culture.

1

Although clans were often comprised of as many as 100 individuals, worldwide populations were so low that clans rarely crossed paths. It wasn't uncommon for people to live their entire lives never seeing people outside of their own clans. The traditions a clan developed and passed down from one generation to the next were therefore all

sui generis and unique to that individual clan. Some matters, such as hunting and toolmaking strategies, were highly constrained by the functional requirements of survival and the environment, and as a result they varied very little between clans. On the other hand, behavioral traditions such as the ritual treatment of the dead or the meaning attached to sounds, gestures, and artwork had a much less direct connection to environmental necessity, and therefore varied widely from one clan to the next.

Clan Languages

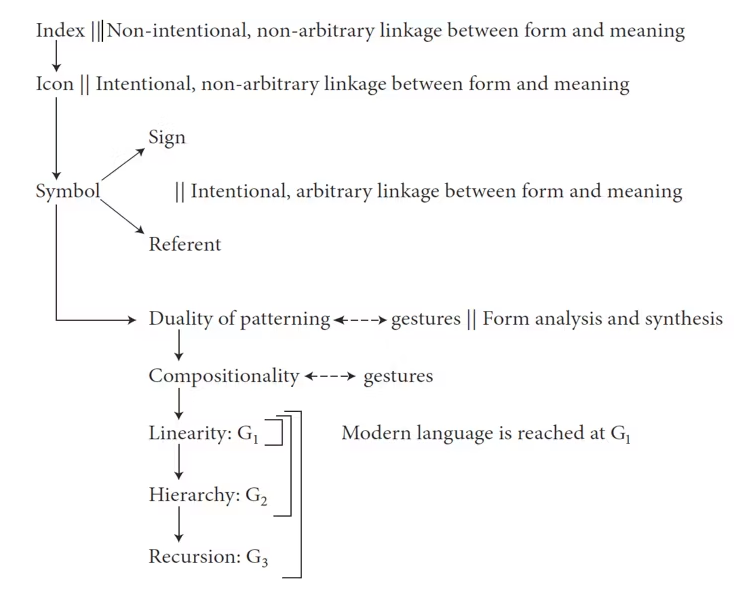

Humans during the Pagsian Turning already used meaning-bearing sounds and gestures to teach and to coordinate behavior. An individual human clan could develop a large lexicon of meaning-bearing sounds and gestures, yet no two clans had the same lexicon.

2 This type of symbolic activity was not unique to humans, although humans relied more heavily on sounds than either neanders or denisova. Neanders would create and communicate meaning using pigment drawings and other visually artistic methods, and for denisova small crafted tools were imbued with symbolic meaning and used for rituals and teaching.

Humans differed from their sentient cousins in another important way, as well: they had an unusually strong drive for planning and predicting. This made them unusually good at coordinating complex hunting strategies, and developing compound tools. Planning and predicting rely on a few core underlying mental capabilities: the ability to identify patterns on a very abstract level, the ability to decompose a goal into a series of subgoals, and the ability to imagine counter-factual scenarios (i.e. to carry out mental simulations of "what if" scenarios and picture the outcome).

These capabilities developed to make them better hunters and foragers. Once the capabilities existed, however, they found other uses as well. By the First Tādhēskō, these faculties were the foundation on which basic syntax and grammar in communication began to develop. The cognitive machinery involved in complex action plans and that required for the hierarchical representation of meaning are nearly identical. Humans developed these capabilities in tandem, and passed this mode of complex thought down from one generation to the next. By the Pluvial Turning, most human clans had developed complex clan languages that they used not only for planning and coordinating activities, but also for telling stories and teaching children practical knowledge and moral lessons.

Shared Languages

As populations increased, clans crossed paths with increasing frequency. These meetings were transitory, so there was little opportunity and even less motivation for members of one clan to learn the language of another. It was only when family groups

expected to share activities over an extended period of time that it made sense for them to put effort into finding common ground for their communication. Historically, this usually only happened after groups of clans had developed sedentary lifestyles and began to build permanent structures. This make intuitive sense: when you know that your neighbors now will still be your neighbors in ten years, and your children's neighbors are likely to be your neighbors' children, you have more incentive to come up with a common system for communicating.

This coordination among clans results in

shared languages. When we talk about a "language" today, we are almost always talking about a shared language. But it is important to recognize that the distinction between clan languages and shared languages is somewhat arbitrary. For example, linguistics who study indigenous languages in southern Africa will talk about the "Khoe–Kwadi Language Family" which is comprised of at least nine (depending on who you ask) distinct but mutually intelligible languages: Khoekhoe, Kwadi, Nama, Eini, Korana, Xiri, Tsoa, Kxoe, Naro, and Gǁana. Each of these languages is spoken by more than a single extended family clan, and yet most of them are classified as "moribund" languages that are in danger of dying out. These do not cleanly fit into the conceptual framework of the binary of Clan Languages vs Shared Languages, but instead occupy a space somewhere between.

The key message to remember is that the real historical process of the evolution of languages in humans is the

exact opposite of what many people assume or have been taught to expect.

3 The diverse multiplicity of languages in the world is not a consequence of some single ancestral language, originally spoken by everyone, becoming "fragmented" over time. Instead, an enormous number of languages spoken by individual fammilies gradually congealed as groups began to cooperate and spend more time with each other.

The emergence of agriculture and similar technologies provided a positive incentive toward shared language development, while at the same time this meant that the emergence of language was always associated with cultural contact and cultural changes. This often meant conflict, which would then change people's attitudes toward cultural differences, agriculture, or even language itself. To understand the complexities of interactions among climate, culture, and the development of language, we will look at the origin stories of two of the original shared human languages: Pūraw, which emerged in the Levant around 12,900 BP; and Yék, which emerged in 10,510 BP along the shore of Ancyllus Lake in northern Europe.

Case Study 1: Pūraw

The year was 14,830 BP, and the Second Tādhēskō had been going strong for several millennia. Depite the fact that a disaster to the north would soon trigger the European Paukos Eisom, the Kebran people

4 in the Levant were living the good life. Their culture had emerged during the previous ice age, so all they knew was a world where winters became progressively more mild, vegetation more lush, and food animals more bountiful than they had been for their parents and grandparents before them. The Kebran people had always hunted small and medium-sized game with bows and arrows, but lately the Levant was so overflowing with life that they rarely had to travel far before they had collected enough mountain gazelle, fallow deer, squirrel, and hare sustain themselves. They also collected grains that they would soak and grind into a paste for convenient eating later. There was so much food around that life was getting almost

too easy.

Natufan Sedentary Hunter-Gatherers

This environment led to a new idea: they could build structures to protect the extra meat and grain they collected, and they could build structures that would protect themselves as they slept. Because they never had to travel far to get enough food, they could return to the same place each day after hunting and foraging. Moreover, the hunting and gathering of grain was so easy that they could spare members of their clan to stay at home and protect the structures and the stored food even while others were out hunting and collecting grains. This shift marked the emergence of Natufan culture, a culture of

sedentary hunter-gatherers, in 14,690 BP.

This idea was not immediately popular with everyone. Some thought it was risky to become too dependent on any one location, or to build structures that could not easily be packed up and moved in an emergency. Others disliked it simply because it broke with tradition, and they distrusted anything new. Many clans had stories, passed down from one generation to the next in their own individual clan languages, of a time when life was much harder, and disasters could strike at any moment, with no cause or reason. Should we not heed the stories that are told by our elders?

This resulted in a cultural split: nomadic Kebran clans continued to exist alongside growing Natufan settlement areas, separated by cultural practice but more importantly by ideology. Tensions gradually mounted between them. Natufan settlements created conditions for shared language as well, and the Pūraw language emerged around the year 12,900 BP as the consequence of coordination and gradual alignment of communication among Natufan clans. This, in turn, made it easier for Natufan communities to coordinate and plan with each other, allowing them to operate as a larger group for everything from food gathering to the building and repair of structures.

By 11,700 BP one of the Natufan settlements had become so well-established that they regularly made plans and speculated about what their families would be doing there tens or hundreds of generations into the future. They gave the settlement a name: Arīḥā. Only a few dozen generations later, in 10,250 BP, the Natufans built a wall around Arīḥā to protect themselves. From animals? Sure. But also from constant and needling harassment from their Kebran neighbors.

Tensions had been building between the sedentary Natufans and nomadic Kebran this entire time. The Kebran people saw the way waste accumulated near the Natufan settlements, and they would say that Natufans were

dirty, turning their noses up as though that dirtiness were an intrinsic character trait of the Natufans: a dirtiness of their souls. The Kebrans saw and resented the easy lives that Natufans were able to achieve through cooperation and communication. "It is decadent," the Kebran would say to each other, "Surely they will suffer some kind of price." Some Kebran clans got so worked up over the moral degradation of the Natufan city-dwellers that they fled the region just to get away from the baleful influence of Natufan culture. Some headed westward to the Sa'hra, while others settled in Kemet, where they established Qadan culture.

Zealous Nomadicism of the Qadan

The year was 10,230 BP, and the Levant and northern Africa have entered a new golden age: the Kara'apian Turning. The Qadan clans who had established themselves in Kemet did not have a common shared language, but they did have a shared ideology. These were the clans who disliked the sedentary Natufan culture in the Levant so intensely that they had to pick up and leave. This proscription against sedantism was passed down from one generation to the next with almost religious zeal: nomadicism was not just a survival strategy, it was an identity.

This zealous nomadicism did not mean that they were primitivists. Their ancestors in the Levant had used sophisticated tools and food preparation methods, and the Qadan adapted these practices to the new geography and ecology in Kemet. They used sickles for threshing grain and grinding stones to transform it into meal. They would find places where grains or other food plants were growing, and would take steps to nurture and cultivate those wild patches for later harvesting. They were clever and innovative, but that innovation was always bounded by their single shared and deep conviction: no permanent settlements, no permanent locations. Although nomadic Qadan clans never bothered learning the languages of other clans in the region, the specific word yera, for

city or

permanent dwelling, was shared across all of the Qadan clans in Kemet, and was a word spoken with disgust.

Over time, however, the younger generations of Qadan began to chaffe under the strict moralistic rules. They would wonder why it was acceptable to build a structure to store grain, but not a structure in which to sleep? Some young families would experiment with new ideas that tested the boundaries of the rules. They created permanent hearths in the ground for fires that they would return to day after day. They would bore holes for tent pegs into the rock itself, knowing that this endeavor was only worth the effort if they came back to that one spot again and again. Fights broke out between clans experimenting with these ideas, since the more traditionally-minded clans saw such behavior as something that might bring disaster down on everyone. So the culture slowly evolved, although it was not without a fight. By around 9,050 BP they had shifted from being a nomadic to a semi-nomadic people, marking the shift from Qadan culture to Faiyum culture.

The Faiyum Culture Wars

Faiyum culture was, unfortunately, unstable from the very beginning. This was largely due to the unresolved tension between their pragmitism and their ideology. For example, it wasn't uncommon for a clan to create and reuse a permanent hearth spot near their tents, while at the same time telling their children to feel guilty about it. A demographic split also emerged over time: those in the north, by the mouth of the river, were younger and more open to change, and eager to hear about far off lands. The river mouth and the sea exerted an almost gravitational pull on young Faiyum young people who had an "itch" to see more of the world. The young Faiyum who moved north were not disappointed: by this time, the Natufans in the Levant had been replaced by the more world-wise and travel-eager Mureybetian culture. Mureybetian ships arrived regularly at the mouth of the river in northern Kemet, with foreign fabrics and pottery to trade, and most important of all:

stories!

The young Faiyum, wide-eyed and curious, desperately tried to learn the language of these strangers, so they could understand the stories of wonderous far off lands! The language the Mureybetian traders spoke was Karā'um, a simplified version of Pūraw that had developed among seafaring traders specifically in response to their constant contact with new cultures. According to the folk stories, when Mureybetians would make fun of the Faiyum people for their broken and stilted attempts at speaking Karā'um, the Faiyum people would laugh, look sly, and simply say: "What do you mean? This is the speech of Kemet!" That phrase became the name of the new emerging language: Rarnij ("speech of") Kemet.

Within Faiyum society, however, trouble was mounting. None of this was acceptable for older and more conservative Faiyum, especially those who lived further south along the river. In southern Kemet they heard stories about the scandalous practices of foreigners, and the way they were corrupting their culture. The "last straw" for many people was the invention of the wattle home. It all started with a single family in northern Kemet who lived by the mouth of the great river. They began reinforcing their tent by weaving river reeds between sticks at regular intervals. These created walls that were light and easy to mend, while also protecting from wind and rain. They showed their friends and relatives, and it immediately caught on, especially among younger families. Wattle huts spread through the region.

With these northerners embracing obviously permanent structures as their home, and speaking their own shared language on top of that, the rift between those northerners and the older more conservative families of southern Kemet grew ever wider. Within only a few generations, culture war tore Faiyum society apart. By 7,550 BP, Faiyum society had been replaced by the progressive and sedentary Merimde culture in the north, and the reactionary and nomadic Badari culture in the south. Those who did not want to deal with the culture war simply fled, with many of them migrating westward into the Sahel.

Cultural Division, and Reunification

The Merimde and Badari spoke distinct dialects of Rarnij kemet. Moreover, the Merimde people had generated a pictographic system for representing words on stone and clay tablets. This innovation was quickly taken up by other cultures in Birit Narim and Cycladia, but the Badari viewed this new invention of "written language" with the same level of skepticism they viewed Merimde people in general. The northern and southern dialects would probably have eventually evolved into separate languages over time; however, these groups underwent a somewhat forceful reunification under Remenkīmi culture in 5,150 BP. As part of this reunification effort, Rarnij kemet was regularized into Ra-n̩ kumat, which became the standard language of the region for several millennia. The clans that migrated to Sahel, on the other hand, established their own Ndɨw culture and used a variant of Rarnij kemet that quickly evolved into the new language, Biu-Mandara.

The paths of descendants of the Pūraw language are shown in blue, along with land area losses (blue) due to flooding during the same period of time.

Case Study 2: Yék

The year was 11,000 BP, and Europe was in the very early stages of Polwes Pleudō, recovering from Paukos Eisom. The Swidrian people were a collection of nomadic clans roaming the Variscides, where the ecosystems were

barely recovering, but the land was infused with fresh water from the melting edge of the glaciers.

Swidrian Glacier-Chasers

The Swidrians hunted reindeer, elk, blue foxes, and arctic hares with rock-tipped arrows and spears. Their movements oscillated, following a consistent and deliberate seasonal pattern of exploring northward in the summer and moving back south in the winter. Over time, as the glacier retreated, they would creep persistently further north with each summer exploration, chasing the edge of the retreating glacier.

Around 10,700 BP the Swidrians reached the shores of a gigantic lake. The lake attracted wildlife from all around, so hunting suddenly became easier. They noticed that the land around the lake was unusually fertile, although they didn't realize this was because the land had been under water until the previous lake had drained in 11,343 BP. Every year the summers were warmer and the winters were a little more mild, and life was good. They gave up their seasonal migrations and built structures along the shore of the lake. The nomadic Swidrian culture was over, replaced by the sedentary lake-side Sandarnan culture.

Sandarnans by the Water

The Sandarnan people lived on open settlements on the flat land by the shore of Ancyllus Lake. They built simple tee-pee style tents using animal skins at first, but over time experimented with more sturdy and complex structures. These structures were built both for human shelter and food storage. They hunted seafowl, seals, and other marine mammals, in addition to fishing and gathering. Harp seals, ringed seals, and bearded seals could all be found in the area; haddock, whiting, and ling fish were all plentiful. Their population quickly doubled, and then quadrupled.

They lived a good life, sleeping in sturdy animal skin shelters by the shore of the lake and always innovating strategies for storing and preparing food that was brought home by the hunters and scavanger parties. Because they were sedentary, individual clan languages coalesced into a single shared language: Yék. This language was purely verbal, and developed primarily around storytelling. The traveling parties would use the language to recount the events of the day when they got home, and parents would create stories to teach and inspire children.

They told their children playful stories about brothers Dyḗus (the daytime sky) and Dīs (the underground) who are in continual contest with each other. Dhéǵhōm (the vast fertile ground) is the consort of Dyḗus, and families would entertain each other with fanciful stories of antics of the family, and jealousies between the brothers who were fighting for the attention of Dhéǵhōm.

Unknown to the Sandarnans, ocean levels continued to rise until the level of the ocean was high above their inland lake. Finally disaster struck: in 9,960 BP the ocean rose high enough to break through and flood the entire region. Because the Sandarans had confidently built their buildings right next to the water's edge, their settlement was completely wiped out and more than three quarters of their population was killed in the tidal wave of incoming water that covered the area.

The few survivers scattered, with the largest group heading eastward through Dnieper-Volga and eventually arriving in the Sarmatic Plain in 9,184 BP. The new semi-nomadic lifestyle that emerged was the beginning of Kundan culture.

Wandering Kundans

For generations after the flood, Kundans felt uncomfortble no matter where they went. They did not enjoy being nomadic, and kept some of the sedentary habits of their Sandarnan heritage, creating seasonal settlements near the edges of forests and next to rivers, marshes, or small lakes. However, the generational trauma from the Ancyllus Lake flood motivated them to move frequently, and deterred them from settling near any body of water so large that they couldn't see across to the other side.

They hunted elk and fished extensively. They continued to develop fishing technology, and created hunting tools from both stone and bone. And the climate was better than anything they had experienced in generations. The recovery climate of Polwes Pleudō made vegetation all across Europe lush, and the wildlife was plentiful. Life was easy and prosperous and the Kundan population exploded, causing them to explore ever-widening areas and seeking out new lands.

One large group of Kundans headed southward and found their way to the shore of lake Euxine in the Caucusus. By this time, enough generations had gone by that the trauma of the great flood was a distant memory that some people doubted ever

really happened. So in 7,685 this group settled on the lake shore and established themselves as the Samra people.

The Very Unlucky Samra

The Samra people built low huts, using larger logs to create a superstructure and weaving thin sticks between them, and packing the gaps with mud to create a rough wattle-and-daub structure. They dried clay to make beakers for carrying water, and decorated them with geometric patterns and depictions of horses and other animals. They shaped stone to make spears, axes, and knives. And perhaps most important of all: they told stories!

The stories had been one of the cultural traditions that kept their ancestors together as they wandered the Sarmatic plain. And as the stories were told and re-told they became more elaborate. When the Samra people encountered other clans either passing through the area or settling along other parts of the shore of Euxine Lake, the Samra stories were a way to befriend people and make an impression. Some of the clans they encountered even spoke a variant of Yék, most likely because they were also descendents of Sandarnans who had scattered in every direction after the flood. But even when the clans they encountered did not speak Yék, the Samra people found ways to tell their stories using pictures and acting out scenes. They were very popular.

The flooding of the Euxine Lake in 7,410 BP, only 275 years after they settled and decided to call those shores their home, was the kind of trauma that would stay with them for generations. Many of the stories they told were about a great flood at the dawn of time that had wiped out almost everyone in the world. To have it happen again felt like punishment and betrayal.

The survivors headed north into the Pontic Steppe, and resolved themselves to the nomadic lifestyle, vowing never to trust permanent structures or sedentary societies again. They wandered for several generations before they began to regain a material culture. These new customs and practices became Yamnaya culture.

From there, everywhere...

In the aftermath of tragedy, the Yamnaya fell into an authoritarian chiefdom structure. Individual clan leaders dictated where the group would go, and what skills and activities every individual would pursue. They rewarded metallurgists, craftspeople who made wheeled carts and wagons, and herders. Agriculture and anything resembling the building of stationary structures was absolutely forbidden.

It did not take too many generations for dissatisfaction with this rigid social system to emerge. Younger generations rebelled, and from time to time groups would simply pick up and leave to explore distant lands and found new cultures. To deal with this, Yamnayan chiefs attempted to "crack down" on dissent, which only made things worse. As Yamnayan society became increasingly beaurocratic and authoritarian, more groups would fee and spawn new cultures in every direction: the Sintashta, the Poltavka, and the Matveyevka were all "escapees" of the dying days of Yamnayan society.

And they all took their language, and their stories, with them to the new lands they settled.

The paths of descendants of the Yék language are shown in green, along with land area losses (blue) due to flooding during the same period of time.