Sṇterían Turning (/sŋˈtɛəɹɪˌãn ˈtɜːnɪŋ/)

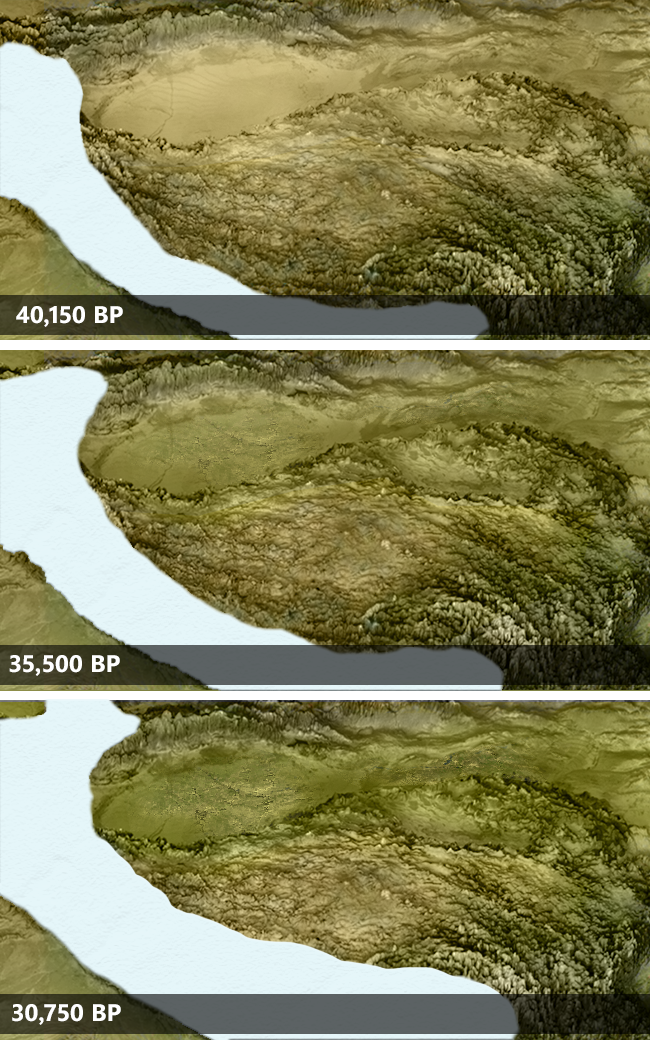

(40,150 BP - 30,750 BP)

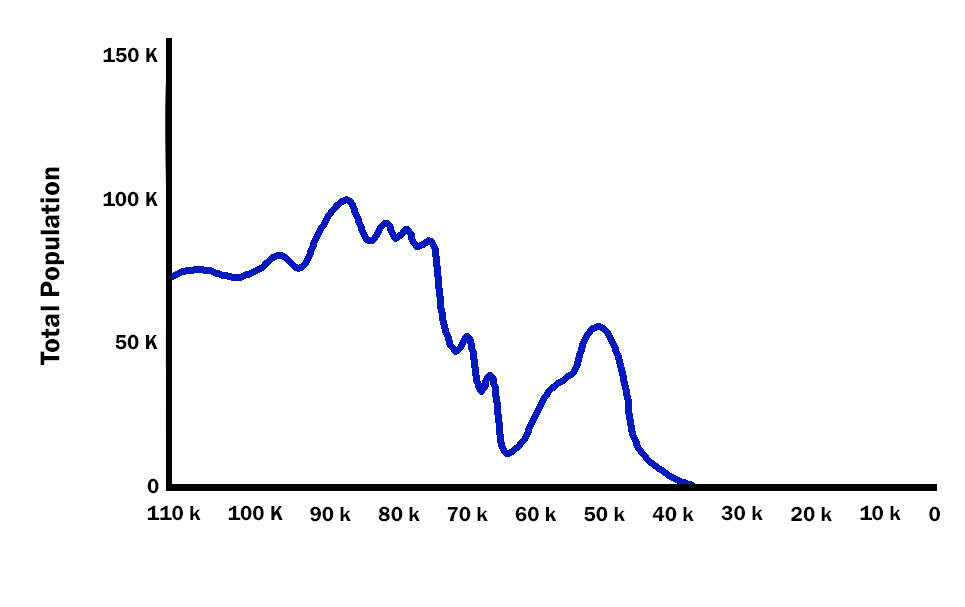

The Sṇterían Turning1 was a period of severe climate instability and environmental anomalies that lasted almost ten thousand years.2

Climate and Ecology

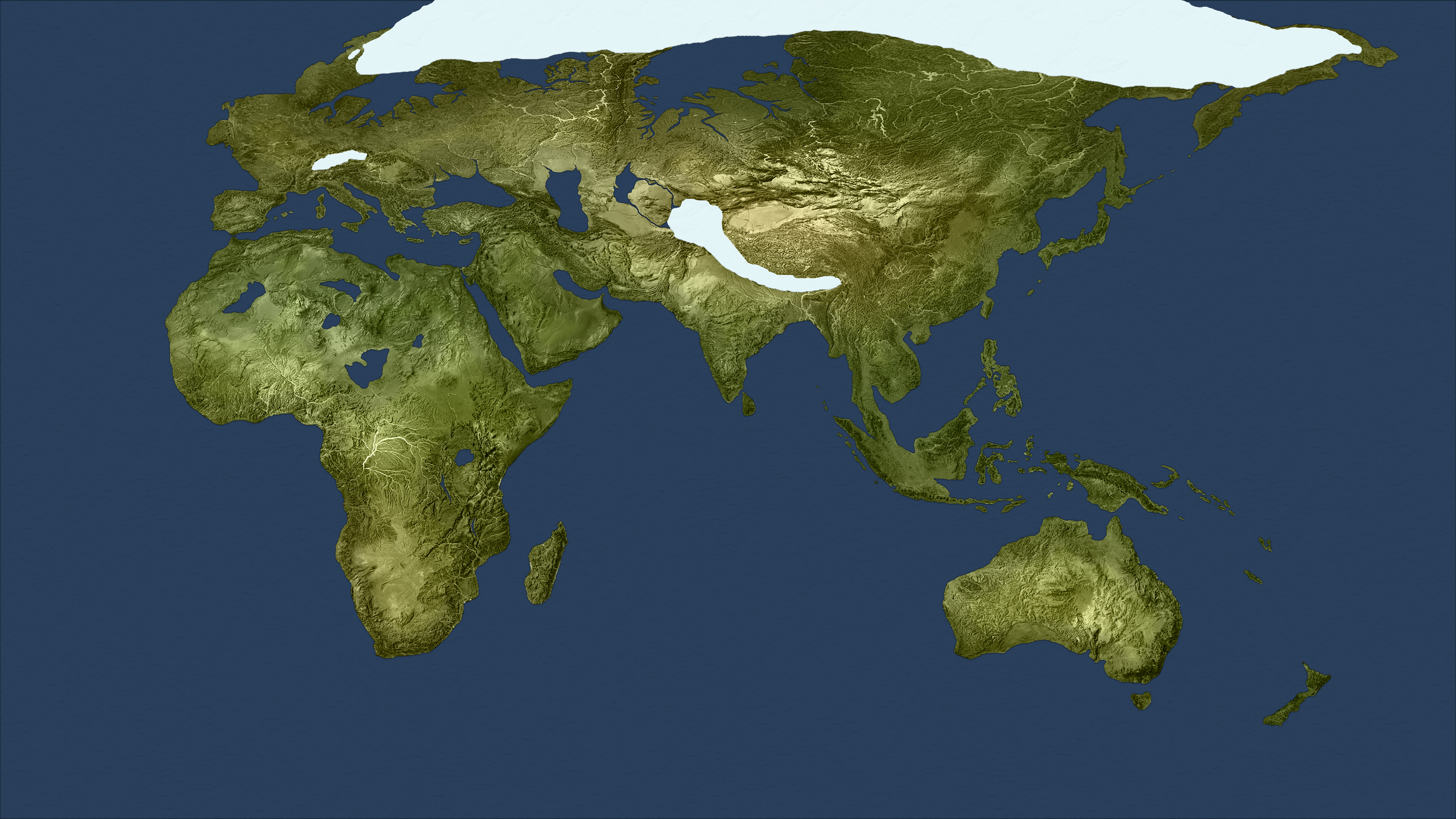

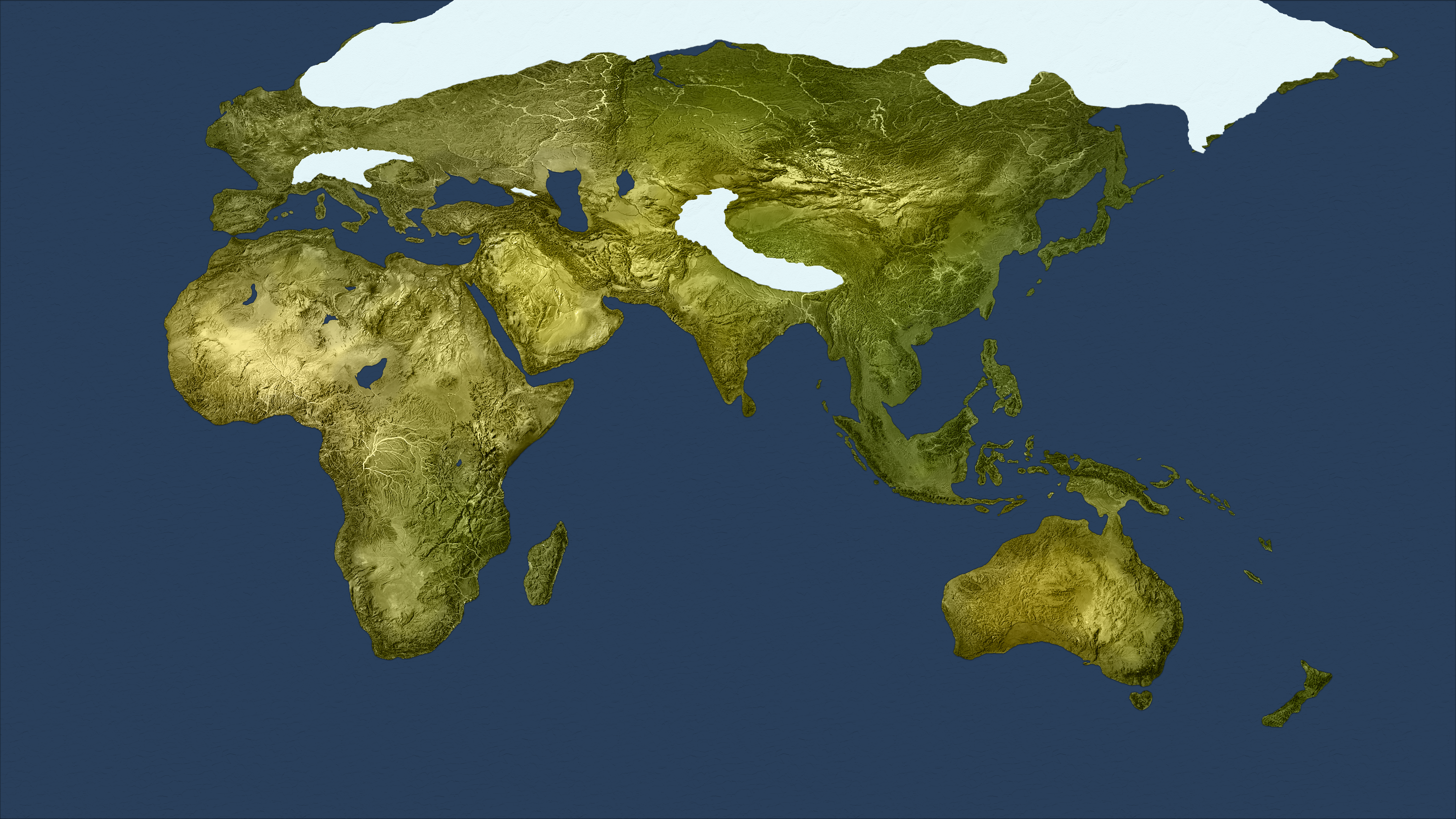

The world climate became extremely unstable and started to show wild and erratic fluctuations right around the time when Laschamps Excursion ended.3 Although the climate would return to moderate temperatures for decades and sometimes centuries between these intervals, the continual pummeling with freezing and dry conditions caused glaciers to creep back down over Skáney, meltwater lakes in Sibir and the Sarmatic Plain to dry up, and deserts to reappear in Sa'hra, Sahel, and Arabia.Aridification of the Belt

With moisture again being trapped by glaciers, the impact on ecosystems in the northern tropical belt followed the same pattern that was seen during the previous era of instability, the Recosian Turning. Forests shrank, lush grasslands thinned out and died. Tâmtu Šupālītu, the gulf that separated most of Arabia from Airyanem Vaejah, shrank and then completely dried up. The disappearance of these inland bodies of water created a positive feedback effect, so that by the end of the turning sand dunes appeared in Sa'hra and Arabia.Greening of Taklamaka

The Taklamakan region of northern Zomia experienced an interesting anomaly during this turning. Surrounded by mountain barriers on all sides, it usually suffered from chronic airidity and was almost always a desert. With glaciers advancing down from Sibir and Altai, however, the periodic mild spells causes an influx of glacier meltwater that led to a period of relative humidity in the Taklamakan region. Over the ten millenia of the turning, the area became lush with vegetation and open rivers. What had been a harsh and impassable region for humans became a corridor that was easy to travel, and invited eastward migration.4Cultures

Neanders suffered the most from this change in conditions, having already had their population culled by the events of the previous turning. The few neander refuges that remained died out, leading to the complete extinction of the neanders during this turning. Humans, by contrast, thrived during this turning. Although some new cultures emerged as the result of migration and exploration, many cultures underwent transitions in situ as the declining climate conditions forced humans to develop new skills to adapt.Emergences

The cultures that emerged due to explorers setting out to establish themselves in new lands included the Solutreans in Armorica, the Kostyonki in the Sarmatic Plain, the Pınarbaşı in Anadolu, the Baradostians in Airyanem Vaejah, and the massive eastward migration across Taklamaka that produced the Nwya Devu, Shuidonggou, and Tianyua. Cultural transformations in situ triggered by innovation and adaptation included shifts from Aurignacian to Gravettian culture, from Ahmran to Antelian culture, from Xhaaxhaanebee to Hamakwanebee culture, and from !Xoo to ǂKhomani culture.Encounters

Most cultural interaction during this turning happened on a small scale, by individual clans from one cultural tradition encountering individual clans from another while foraging or exploring. Many of the cultural shifts during this turning can be attributed to ideas being shared through this process. Similarly, the observation of neanders played a big role in the folk tales of the Baradostian and Satsurblian cultures, although the humans and neanders never interacted directly.Extinctions

The neander members of the mixed Szeletian culture died off, leaving the remaining humans to revert to the local human Gravettian culture, and the last refuges of neander culture also died out during this turning: Bondi in the Caucusus, the Karakol in Tian Shan, and finally the Micoquiens in Iberia. This marked the final extinction of the neander people.5 Human cultures that died off because they were unable to maintain themselves in the deteriorating climate included the Bohunics, the Ust'-Ishi, and the Kashafrud. Those that died off because they made a transition to a new culture were the Aurignacian, Ahmran, Xhaaxhaanebee, and ǃXoõ cultures.Culture Map

This map does not represent all movements by all individuals or clans, but only shows a selection of some important cultural shifts for the purposes of illustration.Turning Type

Period of Decline

Preceded By

Start Year

40,150 BP

End Year

30,750 BP

Succeeded By

The Srīgosian Turning

Footnotes

1. The label Sṇterían was introduced by Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie in 75 BP, and like most of the pre-Srīgosian turnings the name is unattested in writing contemporary to the turning and was constructed by Mackenzie for his taxonomy of turnings. He applied the Yék root for the idea of extinction because he believed that both neanders and denisova went extinct during this turning. This later turned out to be true of neanders, but not denisova. Nonetheless, the name has retained its popularity in large part due to the pleasing similarity in phonetic structure and cadence between this turning (Sṇterían) and the turning that follows Srīgosian). (For further discussion, see Appendix A.) 2. The start of the Sṇterían Turning tied to end of Laschamps Excursian, and the end coincides roughly with what contemporary geologists and paleoclimatologists refer to as the end of Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS3) and the start of the most recent ice age or Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Scientists have a difficult time measuring climate indicators during this period of time in part because of the extreme variability and disagreements among different indicators (see, e.g., Siddall et al., 2008). See Footnote 2 in the article The Srīgosian Turning for further discussion. 3. There is some evidence that smaller erratic anomalies actually began a few millennia earlier, especialy in Europe. For example, evidence from stalagmite and stalagtite formation suggests that starting around 44,000 BP regions in Europe would experience sudden periods of extreme dry and cold lasting up to a millennium, that would then recover over the course of only a couple of generations (see, e.g., Staubwasser et al., 2018). These would be localized, so that (for example) cold dry spell might affect Cycladia but have no impact on the Caucusus or Dnieper-Volga, while later a similar spell might be felt in the Caucusus and Pontic Steppe but not in Anadolu or the Sarmatic Plain, and so on. While these erratic climate events surely added stressors to the local population, they were temporary and localized similar to the climate anomalies that occurred toward the end of the Pagsian Turning, acting as a kind of foreshadowing of the coming changes. 4. The earliest pathway through which humans populated Asia was the southern pathway that began with the Adivasi incursion into Chang Jiang Pingyuan to establish the Sơn Vi culture during the First Tādhēskō. This early wave is responsible for populating southern Zomia, Sunda, Sahul, and most of southern Chang Jiang Pingyuan. Geologists and archeologists recently identified the northern migration pathway that we identify in this work as the Ust Karakol - Tolbaga - Yushuwan sequence during the Pluvial Turning (see, e.g., Goebel, 2015). The greening of Taklamaka during the Sṇterían Turning enabled the third brand of eastward migration (see Li, Vanwezer, et al., 2019) that we identify here with the Nwya Devu - Shuidonggou - Tianyuan sequence. You may sometimes see these pathways presented in scientific literature as alternative hypotheses for eastward human expanstion, but in fact they simply represent waves of expansion that happened at different times. 5. The exact timing of the disappearance of the last pockets of neander cultures has been a matter of debate within archeological and anthropological circles (see, e.g., Higham, Douka, et al., 2014). The complete disappearance of a culture can be difficult to measure when its member dwindle gradually over the course of several millennia and simply disappear rather than being wiped out by a specific inciting event. Nonetheless, the general consensus is that these last pockets of neanders did die out during this Sṇterían Turning.Turnings Index

Type Key