A neander is a person who belongs to the sentient species

Homo neanderthalis, one of the three sentient species of that inhabited the world at the start of the

Pagsian Turning. The population of the neanders (plural) was steady at around 70,000 individuals throughout that turning, and declined as the climate deteriorated reaching a low point of fewer than 10,000 individuals by the end of the

Ougrosian Turning. Although their population began to grow again during the following recovery and golden age turnings, the mass migration of humans into Europe and the bizarre celestial event Laschamps Excursion threw their population into a spiral that led to their complete extinction in 31,050 BP.

Geographic Extent

Neanders originated in Europe, primarily occupying the central regions of

Variscides,

Dnieper-Volga, and

Thracia. They expanded through migration in two major waves: the first in response to the glaciers and deteriorating conditions in Europe during the

Recosian and

Ougrosian Turnings; the second in response to the massive influx of humans into Europe during the

Pluvial Turning. As their population shrank they became isolated in small pockets in

Iberia, the

Caucusus, and

Tian Shan, which died off one by one until their final extinction in the first half of the

Sṇterían Turning.

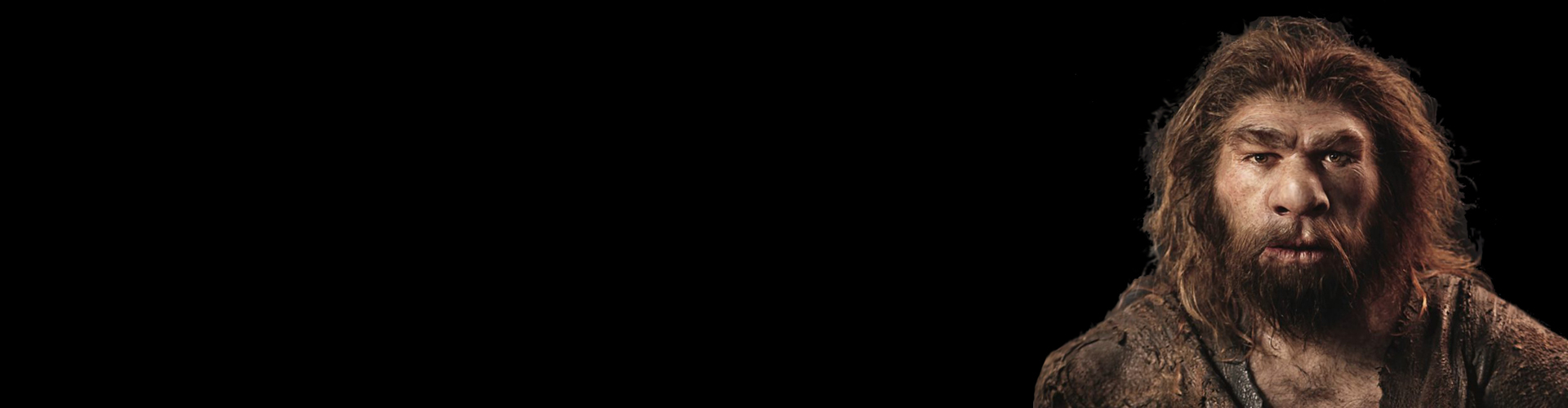

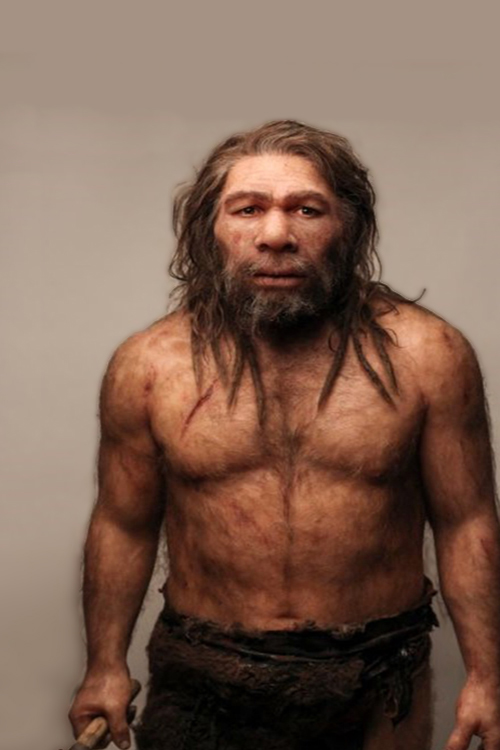

Physiology

Neanders had tan or warm-brown hair and often had blue or green eyes, although brown and mixed-color eyes were not uncommon. Their skin tended to be ruddy and light in color, with a base tone ranging from sandy to sienna. On average they tended to be shorter than both

humans and

denisova. They were hairy, stocky, and strong, which made them better suited to adapt to colder temperatures than either humans or denisova. This adaptation to frozen environments combined with their love of beautity and patterns in nature led them to develop a high proficiency with stone-working, creating both tools and artistic statues and totems.

Lifestyle

The first neanders shared a simple and relatively uniform

Moustrian culture. They were nomadic, and wandered in small groups of extended families, usually between twenty and fifty people. They were sophisticated stone-workers, and hunted with short stone-tipped spears and stone axes. The elders walked with the help of walking sticks. The trait that distinguished them from the other sentient species was their appreciation of beauty. They were artists and musicians, and they painted their bodies with red ochre and grey ash to make patterns.

1 They enjoyed gathering berries and mushrooms. They were deeply affected by the beauty of patterns. When not searching for food, they would spend their time arranging bones or seashells into complex arrangements on the ground, painting their bodies in swirling patterns, or just staring off into the sunset. To modern eyes, their behavior would seem deeply contemplative and peaceful... or perhaps high.

Decline and Extinction

When the climate became unstable during the

Recosian Turning, the neanders fled southward and to the east to escape the oncoming glaciers. This led them to come into contact with

denisova to the east in

Altai, and

humans to the south in the

Levant. Neanders were not aggressive, but neither were they particularly social, especially compared to humans and denisova. Their reaction to encountering new clans was usually to avoid them or to coexist cautiously. They had more success coexisting with humans, inhabiting some shared inter-species cultures with them for a time in the Levant and in

Armorica.

The neander population, already fragmented, continued to decline even after the climate improved. As the human population grew to take over Europe and expand further into Asia, neander cultures contracted into small isolated groups. One by one, the remaining pockets of neanders eventually disappeared. The

Bondi neanders in the Caucusus died out in 38,200 BP, the

Karakol neanders in Tian Shan faded away in 37,960 BP, and the last of the

Micoquien neanders in Iberia died in a cave, looking out at the ocean, in 31,050 BP.

2 That marked the final extinction of neanders from the world.