Recosian Turning (/ɹɛˈkōsiːən ˈtɜːnɪŋ/)

(113,700 BP - 73,110 BP)

The Recosian Turning1 was a time of severe climate instability that lasted approximately forty thousand years.2

Climate and Ecology

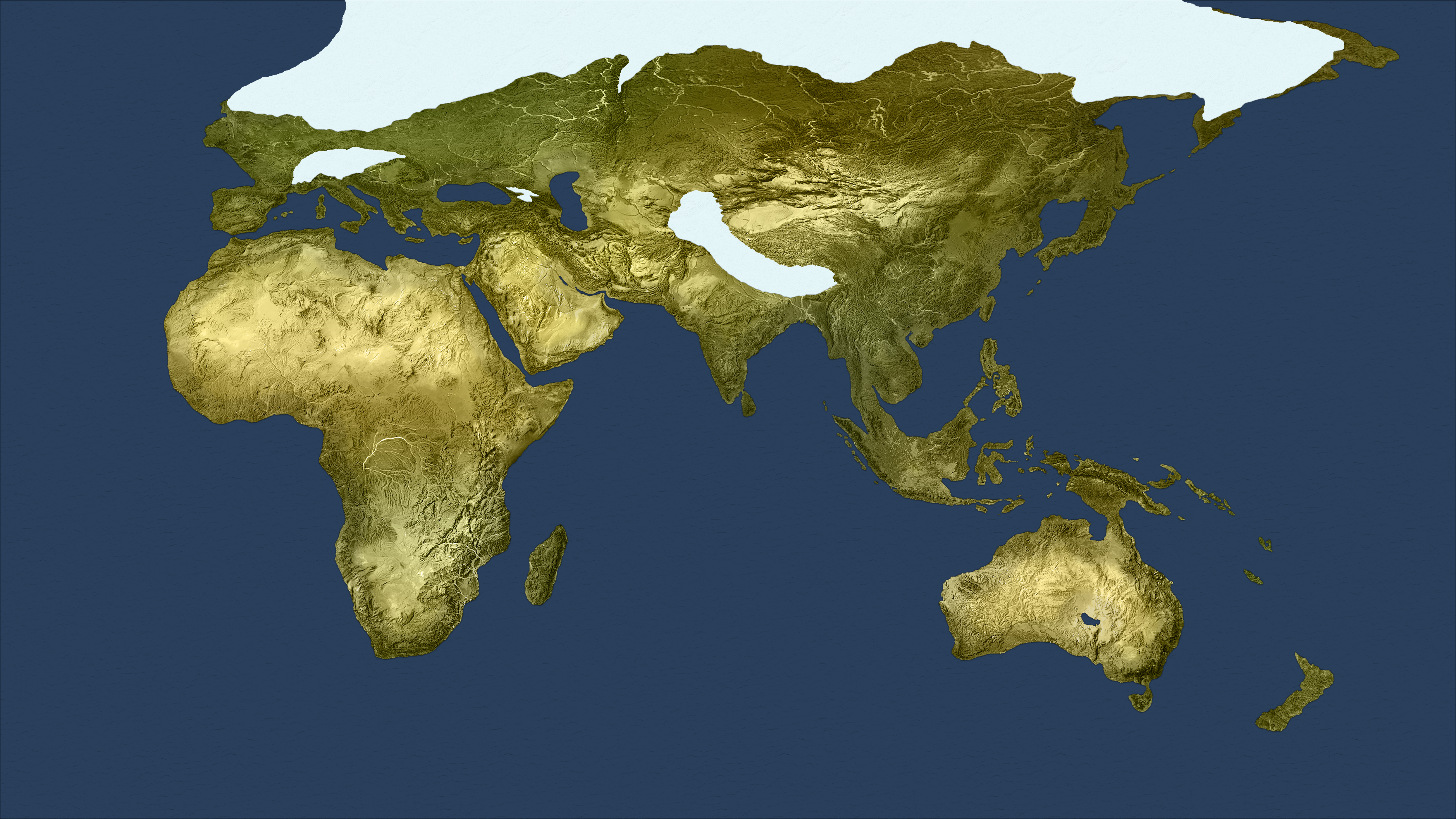

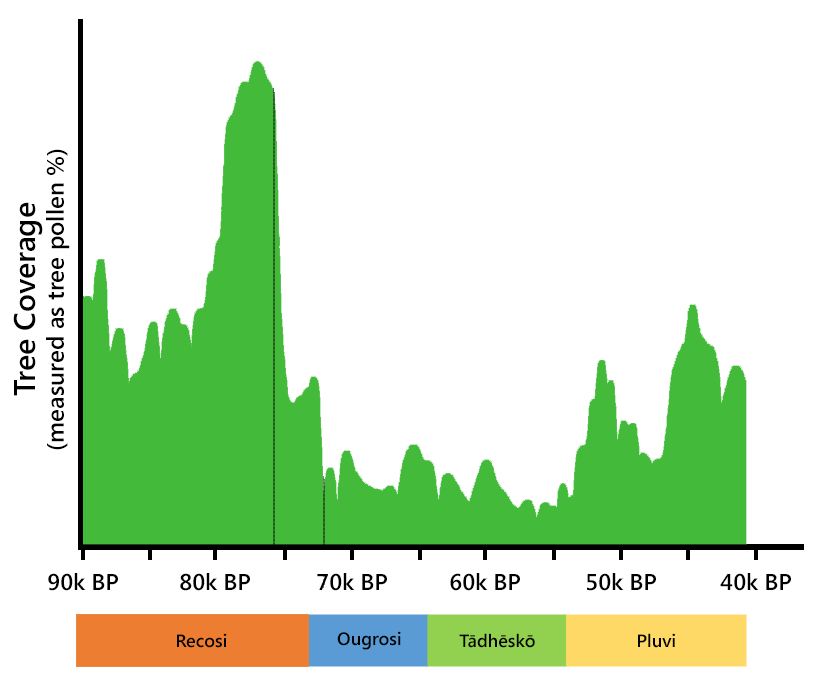

The Recosian Turning began with a sudden worldwide drop in temperature immediately after the Dakhleh Impact in Kemet.3 Throughout this turning, average global temperatures were four to six degrees Celsius cooler than the present day, seasonal temperature swings were more severe, and every century or two would be marked by pulses of extreme cold that would last anywhere from a few decades to a few centuries before returning to the baseline "normal cold" for the turning. Glaciers advanced, sea levels receded, and worldwide drought transformed previously comfortable regions into desert.Glaciation of Skáney (107,000 - 97,000 BP)

The first large-scale impact of the climate of the Recosian Turning was the transformation of Skáney. Glaciers crept down over northern Europe, Eridanos strait was blocked on both ends by ice creating Eridanos lake, and within a few millennia all of Skáney was covered in ice. In nearby Avalonia, deciduous trees were replaced by conifers, and finally forests disappeared entirely, to be replaced by open airid steppe.Aridification of the Belt (97,000 - 85,000 BP)

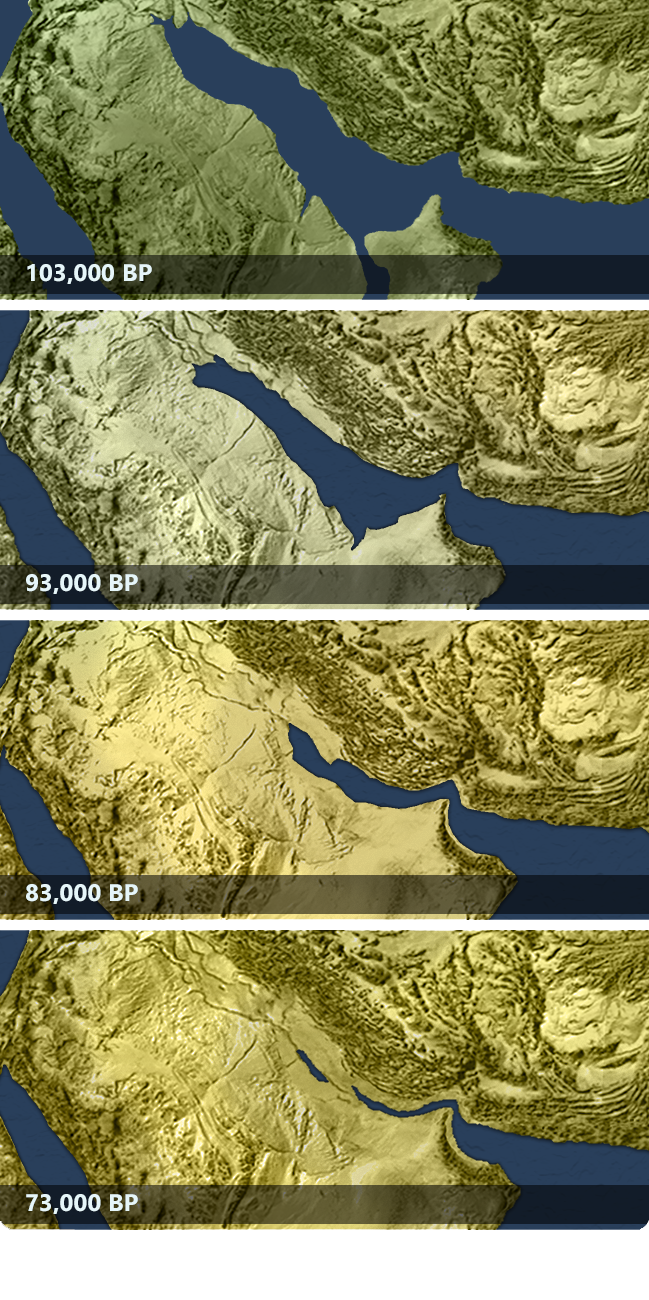

Air moisture across the globe dropped dramatically as water became trapped in glaciers in the north. This led to worldwide drought that had its strongest effect along the tropical belt across northern Africa and western Asia. Forests shrank, lush grasslands thinned out and died. Tâmtu Šupālītu, the gulf that separated most of Arabia from Airyanem Vaejah, shrank and then completely dried up, further accelerating the extreme droughts across western Asia. The disapperance of Tâmtu Šupālītu triggered runaway drought in the inland regions of Arabia, northern Africa, and southern Asia. Sand dunes appeared. Lowered sea levels created a land bridge between Kemet and the Levant, transforming the Eruthraían Strait into the Eruthraían Sea. In Eastern Asia, the lack of moisture transformed Altai and Zomia into cold, airid tundra. Plateaus and mountain passes that once had trees and vegetation became dangerous and inhospitable.Asosan Eruption (89,000 BP)

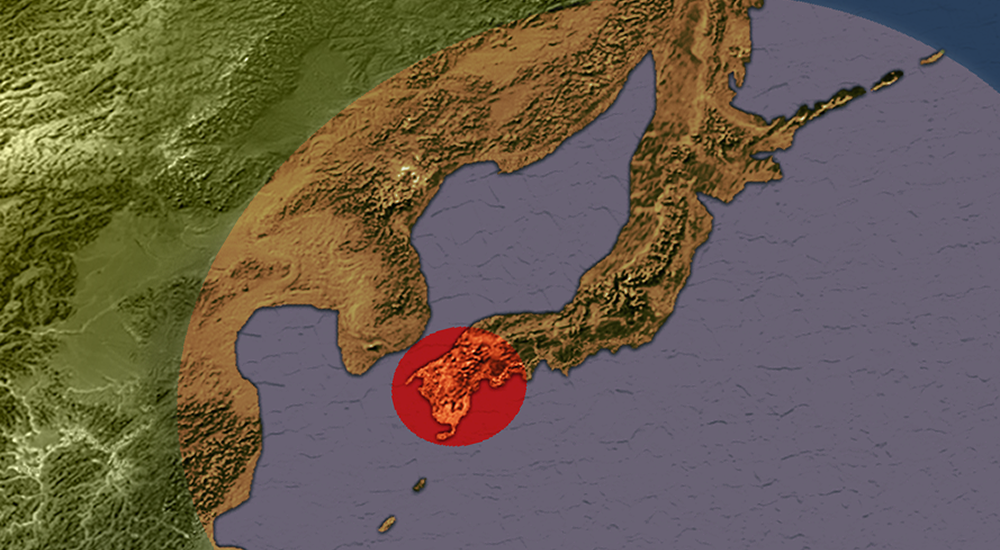

A supervolcanic eruption in 89,000 BP sterilized the entire east coast of Chang Jiang Pingyuan, injected toxic gas high into the atmosphere, and destabilized the local geology so that active volcanic rivers of mud ("lahars") flowed for more than 10 years.4Kasai Ecosystem Collapse (75,500 - 72,100 BP)

The impact of the Recosian climate progressed, and eventually destabilized even the ecosystems in warmer regions such as Western Africa. Up to this point, Kasai had been covered in rich and fertile tropical forest as long as any person could remember. But in 75,500 BP the global balance of temperature and atmospheric humidity hit a tipping point that sent the tropical forest into a death spiral. In only a few thousand years the entire ecosystem collapsed.Toba Eruption (73,110 BP)

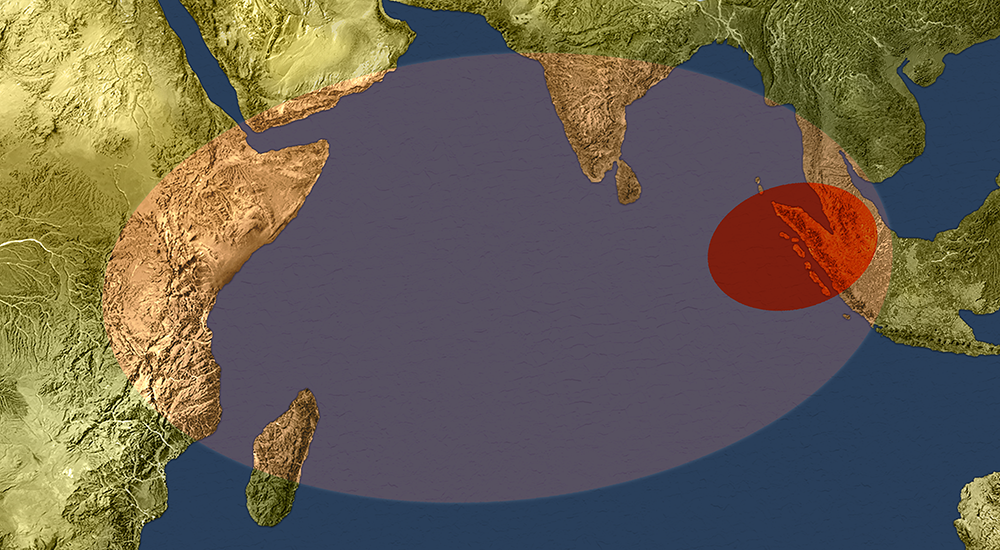

A supervolcanic eruption in 73,110 BP sterilized the entire dry land area of Sunda, injected noxious gases high into the stratosphere, and deposited a 6 inch layer of ash over all of oceania and southern Asia. This pushed the already unstable world climate into a feedback loop of falling temperatures, and thus became the harbinger event for the Ougrosian Turning.5Cultures

As conditions became harsh and travel more difficult, the areas accessible to the nomadic clans of the first cultures shrank and fragmented. This led to fragmentation, specialization, and the emergence of new cultures. It also led to the world's first mass migrations, as clans would set out to try to find an easier life in new parts of the world.6Emergences

Moustrian culture in Europe splintered into regional cultures, giving rise to Micoquien culture in Iberia and Mezmaien culture in the Caucusus. Some adventurous explorer left Europe to try to find a better life in new lands: one established Chagyrskaya culture in Altai, and another headed southward until they came into contact with humans in the Levant, where Emiran culture became the first ever human-neander mixed culture. Aterian humans in northern Africa were traumatized by the disaster at Dakhleh, scattering into the mountains or to move closer to the northern coast. When lowered sea levels produced a land bridge from Kemet into the Levant, some humans crossed over and came into contact with neanders with whom they created Emiran culture. Further to the south, humans up and down the eastern coast from Punt to Namaqua-Natal began practicing a Laetoli culture focused on fishing and foraging for bivalvs, seaweed, and other marine life. This also fragmented after a while, with those in the southern regions shifting to Xãgoã culture, which gave rise to the unique Stilbaai artist collective at Blombos cave. In eastern Asia, the deteriorating climate transformed the mountains of Zomia into an impassable barrier, isolating the denisovan clans in Indus from those in Chang Jiang Pingyuan. While the denisova on the western side of the divide retained their Bah̃iži culture, those on the eastern side gradually drifted northwward and adapted to the colder climate, resulting in Baishiya culture.Encounters

The mixed Emiran culture in the Levant was a model example of cooperation between humans and neanders throughout the Recosian turning. The individual nomadic clans in the region stayed primarily either human or neander, with only a small amount of family mixing giving rise to mixed-race children. However, all of the clans in the region socialized, shared information, and traded openly with both human and neander neighbors. In Chang Jiang Pingyuan, the Asosan eruption forced the Baishiya denisova to migrate inland into Altai where they encountered the Chagyrskaya neanders at Kasang Khim. The denisova and neanders saw one another and were wary and kept their distance. Each thought the other to be standoffish, and was not interested in pressing any interaction.Extinctions

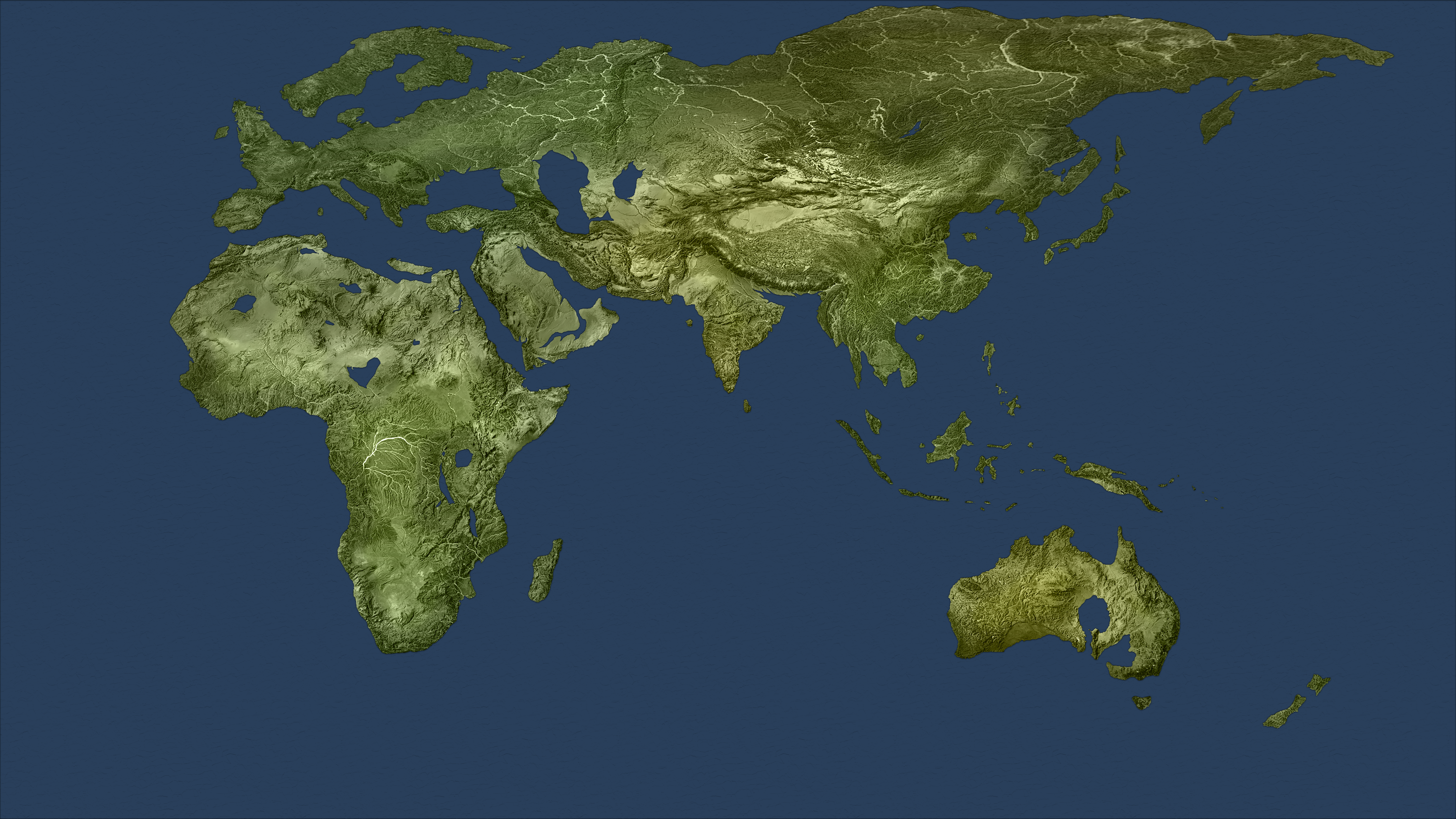

The Toba eruption at the end of the turning completely wiped out the Bah̃iži denisova in Indus.Culture Maps

These maps do not represent all movements by all individuals or clans, but only show a selection of some important cultural shifts for the purposes of illustration. Events are separated into two maps, representing the first half and the second half of the turning, for convenience and legibility.Turning Type

Period of Decline

Preceded By

Harbinger Event

Dakhleh Impact

Start Year

113,700 BP

End Year

73,110 BP

Succeeded By

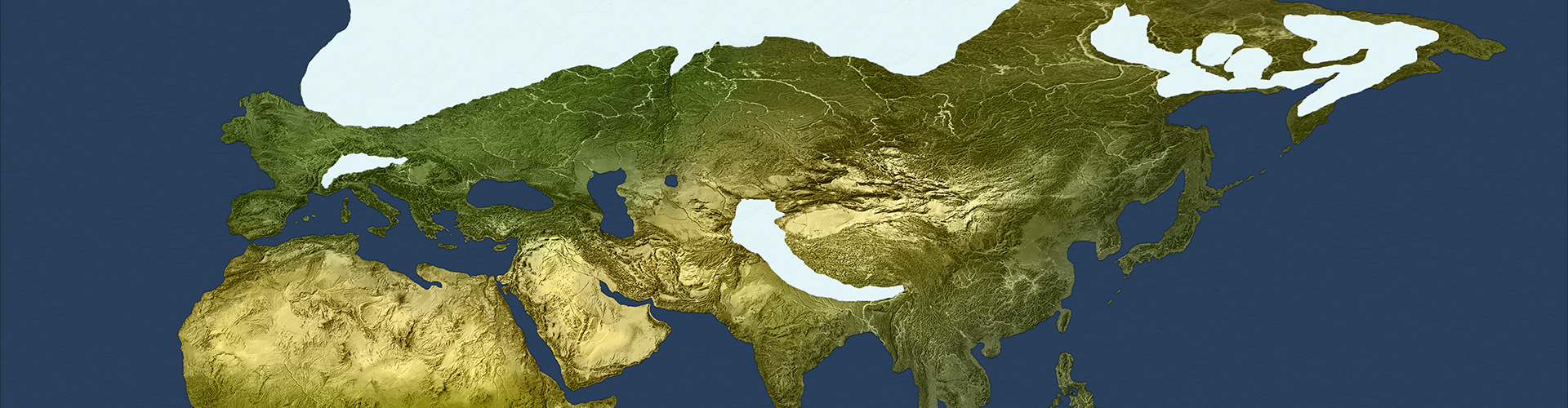

World Maps

Detail Maps

Graphs, Photos, and Illustrations

Footnotes

1. The label Recosian was introduced by Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie in 75 BP, and like most of the pre-Srīgosian turnings the name is unattested and was purely constructed by Mackenzie. Because Mackenzie was unable to find attestations in writings contemporanious to the turning, he simply applied the Yék root for the idea of darkness. This followed a common practice of people in Europe at the time, and was part of the trend that began with Ficino of trying to harmonize all of the turning names to be based on roots in the Yék language family. (For further discussion, see Appendix A). 2. The Recosian Turning roughly corresponds to the the first half of the period archeologists identify as the Early Devensian Cold Stage, specifically spanning Oxygen Isotope Substages 5a, 5b, and 5c. The turning encompasses four extreme cold periods that have tentatively been identified as Heinrich events (101,000 BP, 91,000 BP, 83,000 BP, and 75,000 BP) and a number of short regionally-identified warmer phases, such as the Brimpton and Dimlington Stadials. The end of the turning corresponds to the Stage 4/5 boundry. 3. See Footnote 3 under the Pagsian Turning for discussion of the debate concerning the ecological consequences of the Dakhlah Impact. 4. Asosan experienced repeated massive eruptions over geologic history. Geologists refer to the event at 89,000 BP as ASO-4, and have determined that it measured at least 7 on the Volcanic Explosive Index (VEI). For a detailed discussion of this event and its geological after-effects, see Miyabuchi (2009) and Oba (1991). 5. Initial theories about the extent of the impact of the Toba eruption have been largely dismissed, but in many cases this is an "over-correction" that underestimates the eruption's influence on living things throughout Oceania and Indus, and the climate around the world. This eruption was known to be a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 8 event that instantly steralized the land in the immediate vicinity and created an ashfall for a wider area that lasted several years. The timing of this event made it an obvious candidate for the initiating causal event of the transition to the Ougrosian Turning, and this was the popular view in geological and paleoclimatological circles for many decades. More recently it has been dismissed, with the accepted theory switching to the view that the Toba eruption had only a transitory effect that lasted at most a dozen or so years (for discussion see Ge & Gao, 2020). The evidence for this position, however, is just as circumstantial and suspect as the evidence that had previously been accepted as supporting the opposite. For example, many put forward archeological evidence of homonin both before and after the ash layer in Indus as evidence that the Toba eruption did not cause homonin extinction in that region. As you will see in the discussion of the Ougrosian Turning, however, humans exited Africa and migrated to Indus only a couple of millennia after the volcanic eruption. Thus, although homonin evidence exists both before and after the eruption that does not amount to evidene of continuous habitation by the same groups. Similarly, simplistic climate simulation models are unable to produce a scenario where the Toba eruption causes a millennia-long change in climate; however, these siulations do not take into account the sensitive dependence between climate, ecology, and terrestrial factors such as the wobble of the earth's orbit. Although the ash thrown into the atmosphere by the Toba eruption may not itself be able to produce a long-lasting ice-age, even the most minor shift in the earth's orbit makes the entire system unstable, and can create positive feedback loops that amplify cooling effects and under a timeline of only a few dozen years. 6. The migrations and adaptations described during this turning were not large-scale or coordinated events. The societies of all three species were organized in nomadic clan structures, with clans rarely having contact with one another. That means that the changes that we recognize after-the-fact as migrations occurred against a background of continual movement as clans scavanged and explored the environment. Sometimes a migration would be the result of members of a clan being dissatisfied with their condition and deliberately setting off to find new lands, while at other times migrations were a simple accidental side-effect of nomadic clans tracking animals that also were shifting their habitats because of climate change.Turnings Index

Type Key