Wādī Ḥalfā (/wɒdɪ haɪfə/)

Outdoor Location

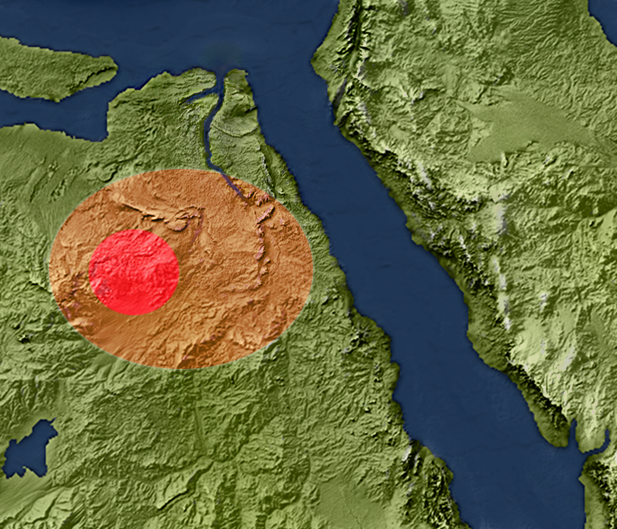

Wādī Ḥalfā was the first location that Aterian humans regularly returned to in the hopes of meeting up with other clans for ritual celebrations and to share stories and ideas during the Pagsian Turning. It was an attractive spot for gathering in western Kemet. Shallow lakes and the tributaries that led into the great river to east broke up the landscape and kept the grass growing green and high even during dry periods. Its popularity increased slowly for centuries, until the region was devastated by the Dakhleh Impact.

Emergence

Prior to the emergence of the Wādī Ḥalfā pilgramage, it was not unusual for members of a human clan to go their entire lives without seeing anyone from another clan. The north African droughts of 123,820 BP pressured a number of human groups to migrate eastward, leading to an unusual number of "other people" sightings in the Wādī Ḥalfā region. Between the beautiful and bountiful landscape and the novelty of the chance to interact with new people, clans began to selectively return to the location regularly, often once or twice a year.Culture

Because clans were so isolated, people communicated within their clan using their own individual clan languages. These systems of sounds and gestures were passed down from one generation to the next within the clan, but often were completely different from the conventions practiced by other clans they met. As a result, the main way that clans communicated when they met at Wadi Halfa was through gesture and dance, or the demonstration of practical skills. A person could sit in a cleared patch of ground near the water and start carving and decorating sea shells and, if it was during the popular season in Wādī Ḥalfā, an audience was almost certain to gather to watch. After a while, sometimes another individual might sit down across from the first and attempt the same skill, the two of them using gesures to teach and communicate. Meanwhile, young boys would chase eachother around in the high grass and play tag by the water. In the evening, people would often light large bonfires and simply enjoy the comfort of communing in a larger group than they were used to. The location was especially popular in the autumn, and the mood at these gatherings was almost like that of an outdoor festival. Families eagerly anticipated the new and unusual things they might witness and learn when they met other clans.Structures and Artifacts

As this tradition recurred year after year, passed down for generations, people even began to alter the landscape in anticipation of their next visit. They would clear areas to be reused as communal fire pits, knowing they would search for those same clearing when they returned next season or next year. They started grinding deep holes in the sandstone to insert supports for their makeshift tents, so that when they returned again later they would know the exact spot to set up camp in order to have a study refuge. The site was particularly popular in the autumn each year, and attendence grew every year.Destruction and Aftermath

In the autumn of 113,700, during a period when many human groups were communing at Wādī Ḥalfā, a barrage of meteors that lasted six days and nights devastated the landscape. The meteors approached the ground through the atmosphere at a shallow angle, so that about half of the exploded into fireballs in the air without ever hitting the ground. The center of the meteor impage was about 450 kilometers to the north and west of Wādī Ḥalfā: close enough to be deadly, and those who survived knew that event to be the loudest sound and most intene heat they had ever experienced. The humans felt betrayed by their environment. Up to this point, life had been tough but the world was largely predictable. Humans excelled at understanding relationships of cause and effect. A lion was scary because it was strong and could overpower you; however, what made it less scary was that it was understandable. The lion searches for food and protects its territory and its young. When you understand what the lion wants, and what the lion might be scared of, you know what it is going to do. That makes it less of a threat. The Dakhleh Impact was an incomprehensible monster. It appeared quickly and as if by random, and disappeared the same way. There was no way to understand what it "wanted" or why it chose to bestow so much death upon the living things in that area. This made it a much more scary predator than any animal, and it filled the humans with dread. What did they do wrong? What could they do to stop it, or at least anticipate it, in the future? No answers appeared. Over the next few years, the permanent damage caused by the meteor impacts could be seen. The top layer of ground had been steralized, so that no new plants grew and all of the wildlife was forced to move away. Bigger changes were in the air, as well: summer heat was getting more intense, while winters were getting dryer. Even the plants in the area started to change: pleasant tall grass was replaced by shorter, tough scrub brush. Eventually, the surviving humans had all moved away, northward or eastward to find the coast so they could live off of marine life. Wādī Ḥalfā was completely abandoned, and soon forgotten.

Location Type

Pilgrimage Site

Established

123,000 BP

Abandoned

113,700 BP

Alternative Names

Arkin 8, وادي حلفا

Location