Paris

All roads don't lead to Paris, but a great deal of them certainly pass through it.

It's the largest city in Europe, and one of the largest in the world. Paris is Europe's largest hub for both trade and academics, and the capital of the world's most far-reaching empire. It was the first city in Europe to have streetlights installed, and the first in the world to create a publish transportation system with their network of trolleys.

These days, however, Paris is not quite the sparkling gem of a city it used to boast of. The violence of the revolution and the oppressive Jacobin regime currently in power has left the city on edge. Shops sit empty with smashed windows, revolutionary graffiti pops up on old stone walls, and the inhabits guard their tongues closely, lest they be dragged to the tribunal and accused of treason.

Demographics

Until the social upheaval of the revolution, the neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain was home to the extravagant town houses of France's noble class. They made up only 3 or 4% of Paris' total population. As of 1794, the number of nobles in the city has plummeted to only a couple hundred, as many of them have fled to Ireland to avoid the violence of the Terror. Those that remain keep to themselves and avoid flaunting their wealth.

The middle class of shopkeepers, merchants, artisans, professors, doctors, and lawyers has progressively expanded over the last century. The rise of automation using pathstones to power machinery has led to an economic boom for workshop owners. The middle class, or bourgeois, make up about 40% of the population and currently run the government.

The bulk of Paris' population comes from the poor working class. The automation that led workshop owners to grow rich also drew farmers from the countryside in pursuit of jobs. The exodus of the countryside was helped along by the growing problem of wraiths, which continue to plague France's villages and leave scores of deaths in their wakes.

The majority of Paris' residents are white Europeans, but as one of the world's major trade hubs, it is home to many cultures from all over the world. People of all colours meet in Paris' markets, and no one would bat an eye at hearing a foreign language spoken on the street. One of the largest groups are those from French Muisca. Muiscan people can be found in the lowest rungs of society working as labourers, all the way up to prestigious doctors or merchants. The Muiscan people's footprint in Paris is noticed every time one walks past a Muiscan Cafe and smells spicy meats or fermenting chicha.

As France is an Arbitrist country, the majority of Parisians keep their soul cats at their side at all times. The already densely crowded streets are made even more treacherous by the cats twisting between everyone's feet. But, as it is a major hub for all of Europe, Catholic visitors who walk alone are unremarkable and receive little more than a disproving glance. At the worst, they might be refused business at a cafe or shop.

Infrastructure

Trolley Network

The most notable infrastructure in Paris is its revolutionary trolley system, established in 1767. The trolleys were inspired by the Path Carriage; less than ten years earlier, the Royal Transportation Authority had been established to oversee the building of rails for a path carriage network in France. Once that was underway and running smoothly, the Authority decided to construct a smaller network within Paris itself.

The reality of Paris' muddy, high-trafficked streets made it infeasible to place the pathstones that power trolleys cars in the ground, as is the case for a path carriage. Instead, wires stung over the street provide power via a metal arm reaching up from the trolley. Pathstones strategically placed along this network of wires, suspended in a net of copper cords, send energy through the system to give each trolley a well-timed burst of power.

The trolleys used in Paris consist of a single steel box with wheels that runs on a track. The front half of the car has wooden benches, while the back half is standing-room only. It costs 1 sous to ride standing, and 5 sous for a seat.

Currently, the network runs only through the more metropolitan areas of the city. No trolley will be scene in the warren of alleys and muddy streets that make up the bulk of Paris' residential neighbourhoods. They run along the major thoroughfares and stop at locations with an upper-class clientele in-mind.

City Lights

Paris' streetlights were installed in 1678. Traditionally, pathstones for lighting had to be set up by an Alzamatrist and then left on until it burned out. This made them impractical except for special occasions or in a royal court wealthy enough to have an Alzamatrist on hand to light and un-light each stone as required.

Advancements throughout the 17th century led to streetlights being installed in Paris before anywhere else in the world. The key aspects of the formula used to power the lights were that it had a timer coded into it telling the stones to illuminate at a certain time and then turn off again after so many hours. Additionally, it was set up to trigger surrounding pathstones, so that each light in the city could merely be connect to a handful of hubs with the formula, rather than inscribing it on each light individually.

The formula has needed to be updated several times since the initial installation. Astronomic shift and the change of seasons eventually led to the lights turning on in the middle of the day and turning off again just before midnight. Every few years, an Alzamatrist updates the formula to re-align them with the clock.

Colour Connotations

The types of pathstones used say a lot about a neighbourhood. While the cheapest neighbourhoods have no lights at all, those straddling the edge of middle-class use the cheapest smokey quartz with a yellow-brown hue. These lights cast the muddy streets in a dim, pale brown light.

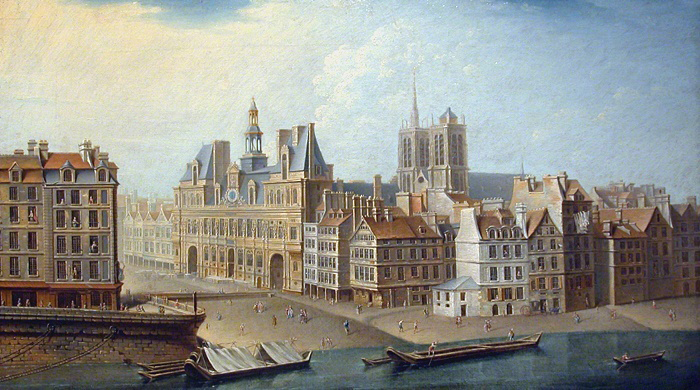

Around major government buildings, such as palaces, prisons, and the Hôtel de Ville, bright green emeralds cast a strong green light on the surroundings. Even though the Bastille sits in ruins, the green light around it serves as a reminder of the state's power.

The purest, clear quartz is the preferred pathstone for lighting. It gives off pure white light and is found in the wealthiest districts.

Other districts have their own flavour. For example, areas built up by the Arbitrium Church tend to use the light-blue aquamarine favoured by the church, and the silversmith's district imports many amethysts from Brazil along with their silver, giving their neighbourhoods a distinct purple hue.

Architecture

Paris is a dense, crowded city. The majority of immigration in the past century ended in the heart of the city, causing housing lots to get smaller, skinnier, and taller. Many buildings are four, five, or even six storeys tall. Most buildings are made of stone bricks, or at least were initially made of stone until haphazard wooden additions were added higher and higher. Buildings are crushed together, with narrow alleys below and a forest of chimneys above.

Most of Paris is unpaved. Cobblestone roads are found in the wealthier areas of the city, but most of the roads are still dirt. In the spring, melting snow turns the roads into mud, which then mixes with the horse manure.

Upper-class areas of the city, the major thoroughfares and government buildings, are much nicer. Here you can find cobblestone boulevards and grand stone buildings.

Medieval castles like the Conciergerie and, until recently, the Bastille, break up the urban squalor. The skyline is peppered with the steeples of grand churches, like the iconic twin towers of Notre Dame, and the dome of Hôtel des Invalides.

Type

Large city

Population

618,000

Inhabitant Demonym

Parisian

Owning Organization

Characters in Location