Ljoðarhall (ɫjʊːðɑrhɑl)

A ljoðarhall (translated: sounds hall/hall of sounds) is a type of assembly hall found in nearly every settlement in Auregelmir. Most are built and owned by a cooperative consisting of associations, clubs, and local individuals, though it is not unheard of for the herað to fund a community's ljoðarhall.

Day-to-day it is used as a place where people come to drink and sing, but serves many other purposes depending on the size and function of a settlement. People gather here to celebrate the holidays with their neighbors, receive important messages from the government, host events, or in smaller villages, conduct court for minor offenses. It is the center, often literally, of the community.

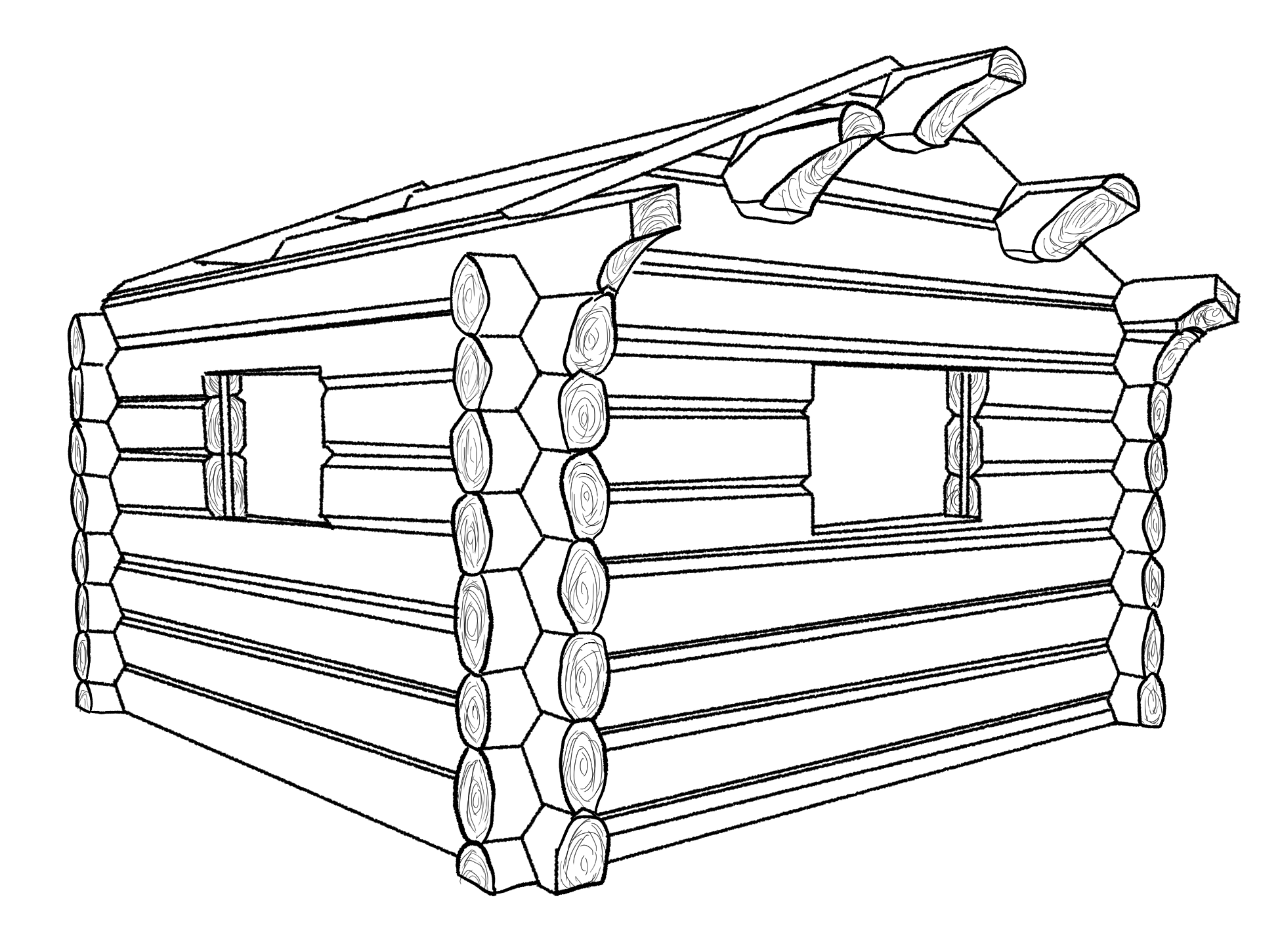

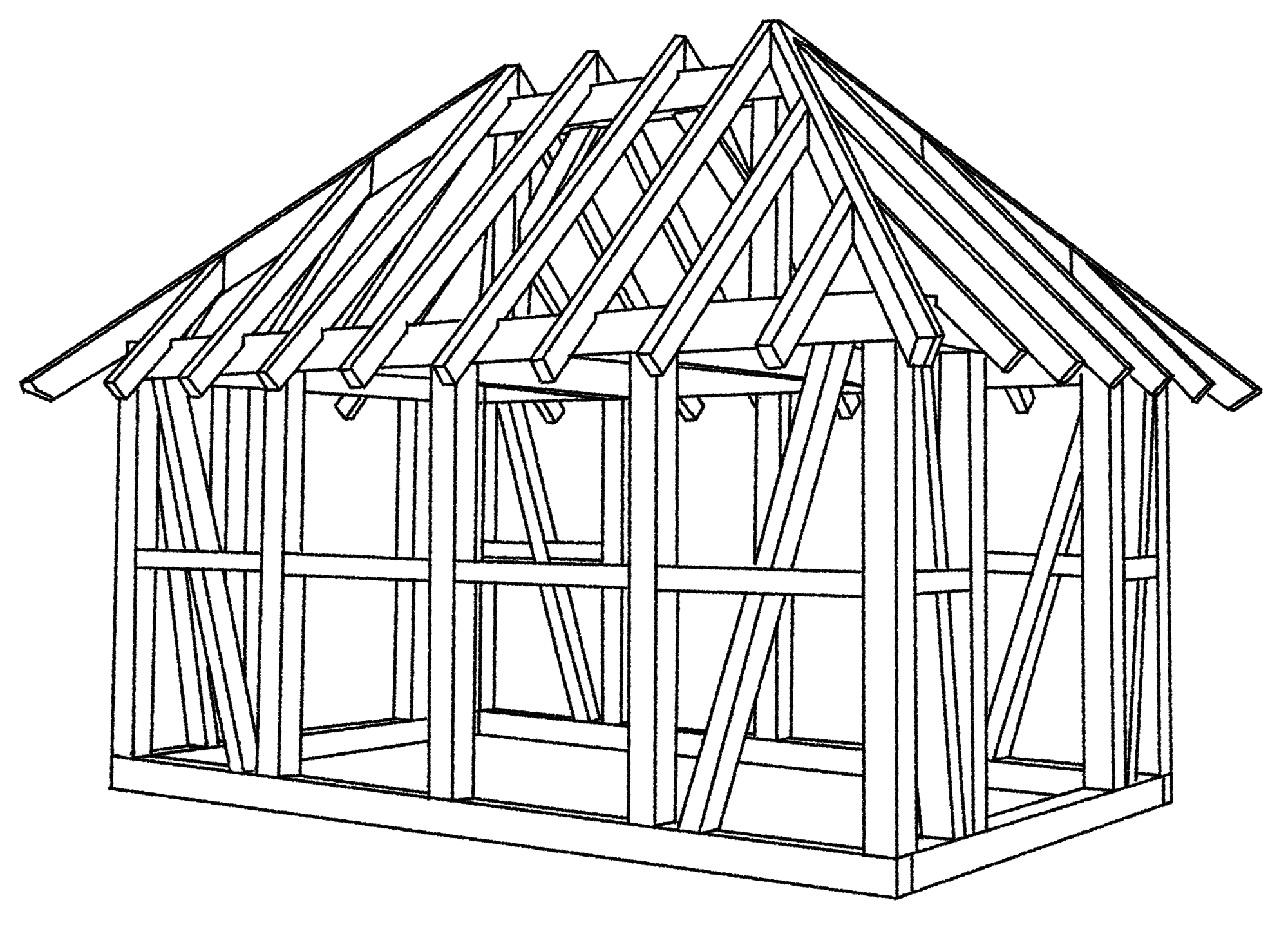

As it became more common for families to live in individual houses, the hall became a standalone structure, often being the largest building in any given settlement. While the people lived in simple houses with thatched roofs, the ljoðarhall was given the little extra. Tall stone foundation, old growth pine walls, and slate tile roofing.

How the halls look today is very dependent on its location, and they may not be immediately recognizable from one town to the next. Many swear on building them exactly as they were, while some want insulated walls and fine glass windows. Regardless of looks, they are still used the same way today as they were a thousand years ago.

Day-to-day it is used as a place where people come to drink and sing, but serves many other purposes depending on the size and function of a settlement. People gather here to celebrate the holidays with their neighbors, receive important messages from the government, host events, or in smaller villages, conduct court for minor offenses. It is the center, often literally, of the community.

History

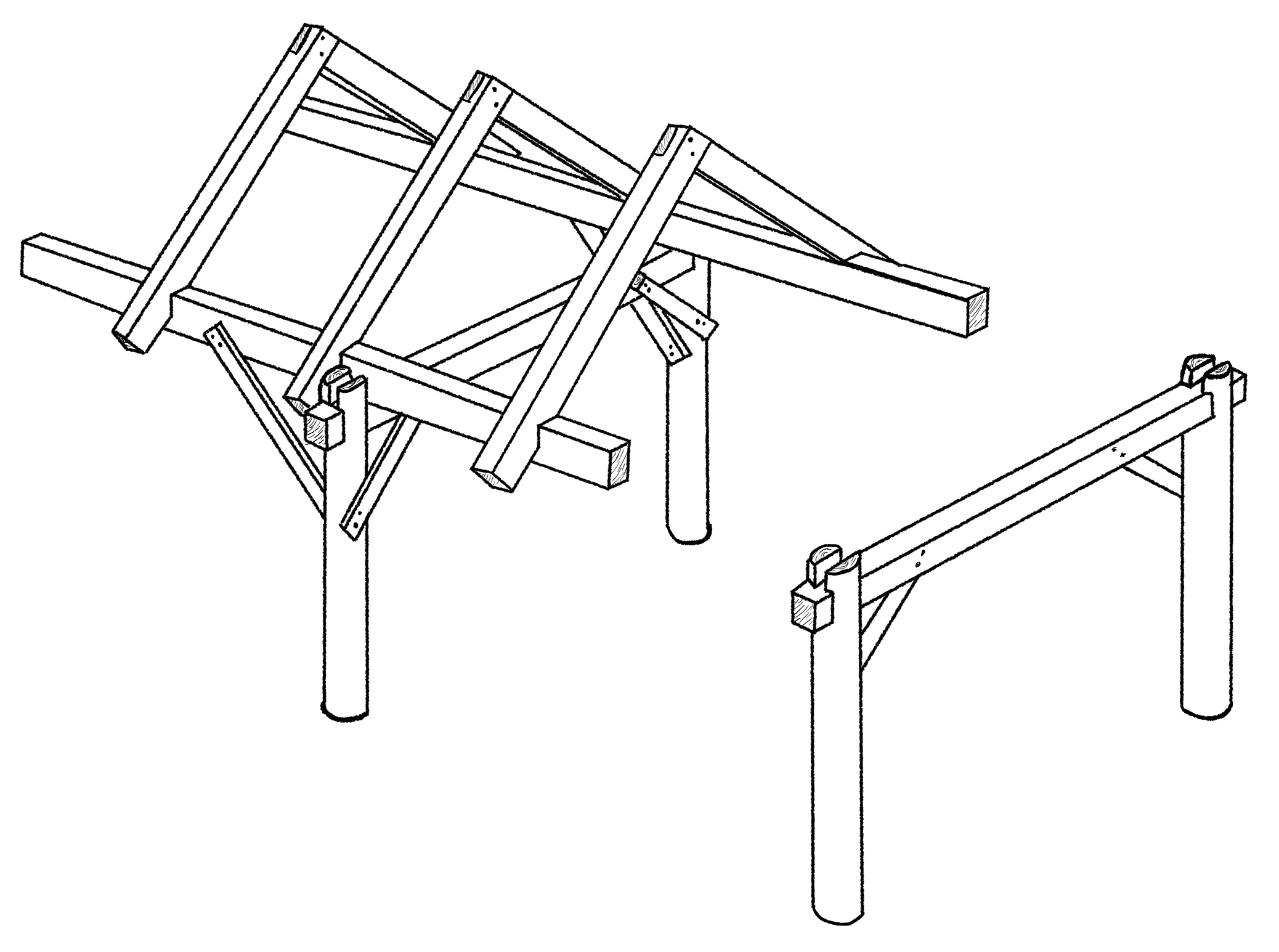

The ljoðarhall has its origin in ancient times when a regular Auregelending settlement consisted of a single longhouse. The main hall of the longhouse, making up roughly two thirds to four fifths of its length was called the ljoðarhall. Here you could find a long fire pit, benches, tables, cooking utensils, and sometimes beds. It was the working man's common room where all their daily indoor activities took place. In the evenings, after a hard day of work, they would gather here for food and drink, and of course song. The tradition for having a place dedicated partially to singing is believed to be the reason so many ancient aure songs are still around today.As it became more common for families to live in individual houses, the hall became a standalone structure, often being the largest building in any given settlement. While the people lived in simple houses with thatched roofs, the ljoðarhall was given the little extra. Tall stone foundation, old growth pine walls, and slate tile roofing.

How the halls look today is very dependent on its location, and they may not be immediately recognizable from one town to the next. Many swear on building them exactly as they were, while some want insulated walls and fine glass windows. Regardless of looks, they are still used the same way today as they were a thousand years ago.

Song games

Games of song and rhyme are a nightly occurrence in the halls, but none more popular than "I Ljoðarhalli" (translated: In/inside [the] sound hall/hall of sounds). The game starts with all participants singing the first verse of the eponymous song. It goes like this:Syng med den stemmen du har

Ein kar, uklar, men stemmar i par

Ljoðhalljydar ljyder ei rar

Translation tooltip here

The participants will then take turns making their own verses, sing it out loud, and have the rest of the group repeat it. They set their own themes and rules each time the game is played, though a common baseline is to have at least four rhyming words in each verse. Players are eliminated when they are unable to make up a verse in a reasonable time, thus breaking the flow of the song. The winner, or winners if the game just keeps going, get their verse added to the song the next time they play. Some reset their games after a week or a month, while some never end, creating songs with hundreds of verses.

Comments