At least we here did all we could to break the chains of oppression. Those cowardly hogs from the other counties and duchies got all they ever could have wanted since we did the heavy lifting and brought fear into the hearts of the blue-blooded bastards!— Heins of Gilbrenen, 1543

The Nordhei Uprising was an insurgency organised by the serfs of the

Aristocratic Republic of Rueken along with the assistance of the

Peasants' Republic of Aussel during the

Sarzin Conflict. The inhabitants of the

Duchy of Nordhei, tired of harsh taxes, forced labour, and the physical punishments that their manor lords could inflict upon them, used the ongoing conflict to stage a rebellion. Thier hope was either to spark a greater uprising throughout the entire country, or if that failed, to force their government to grant them more rights.

Prelude

Serfs in Rueken had for centuries suffered under the tyranny of the upper classes. Some, like those men and women who had declared their independence and established the nation of Aussel, had managed to do what many considered the impossible and created a peasants’ republic. Yet despite that success, the conditions only worsened for those in the heart of Rueken.

The Sarzin Conflict

In the year 1540, around 23 years after the peasants of Aussel had secured their independence, a new conflict between the Ruekish and Ausselians had begun.

Kilas ven Leiberge-Kattel, the Duke of Nordhei and Chancellor of Rueken, launched an amphibious invasion to capture the islands of

Sarzin and

Farten.

This unprovoked act of aggression led the way to the

Sarzin Conflict, a struggle which the Ruekish viewed as a chance to wash away the taint of previous military failures. For the people of Aussel it was something far greater. They saw it as a threat to their freedom and a trial to test their might and determination to stand up for their values.

Home and Away

Seeing the armies of their duke sailing to war against free peasants had infuriated many of the serfs in Nordhei. They were envious of the freedom that their northeastern brothers had gained and thoughts of rebellion spread rapidly across the countryside. With the duchy’s finest heavily armoured units away from home, the serfs saw their opportunity.

Many of the organisers of the uprising hoped that by defeating the nobles in their home duchy, the flames of revolution would spread to the rest of the country. Their most optimistic dreams envisioned a new free peasants’ republic of their own and a potential union with the peasants of Aussel, while the realists only hoped for reforms.

Uprising

An end to the arbitrary beatings, uncompensated work, and heavy taxation is at hand brothers! No one will free the people of this land, but the people themselves. Our future is our own to forge and we’ll forge it with blood and steel!— Heins of Gilbrenen, 1540

The rebellious serfs had assembled with whatever arms and armour they could find on the 10th of

Kateaqteril near an old burnt alehouse that was located between a few villages. Under the leadership of

Heins of Gilbrenen, the group figured out a plan of attack. Their first objective had to be something that would provide them with supplies, but in addition to that, it had to incentivise more uprisings.

Pillaging of the Estates

Two targets were set after their first meeting at the alehouse. One group of insurgents had been tasked with securing a nearby harbour while the rest were to ransack the local estates. With overwhelming numbers, the rebels made swift work of the few men who stood on guard.

The manor lords and their families were dragged outside, where they were subjected to similar physical punishment that the serfs had to endure for years.

Ausselian Assistance

During the planning phases of the uprising, the leaders of the rebel forces had managed to make contact with the Ausselian government.

Eager to help sow the seeds of chaos in the enemy’s homeland, the armed forces of the peasants’ republic sent out supplies and weapons in secret. The port was essential for recieving the goods.

Long have we awaited the chance to rip them apart. All our years of pain and anguish and the rage of our forefathers who endured the same has built up within each of us. The time to unleash that fury has come. Leave none alive!— Odo Wudiger

Battle of Gettehav

After ransacking several estates and slaughtering the inhabitants, the serfs regrouped at the harbour, where they received supplies and weapons. While they rested there and planned their next attack, a group of armed assailants launched an assault on their campsites. Lord and ladies from other nearby lands had sent forth their retinues to eliminate the threat, but the rebels were ready for them.

The nobles’ retinues had engaged the serfs in combat in the early hours of the morning, using the dark to conceal their movements, but as they had been tracking the rebels, they themselves were being followed.

A small group of Ausselian volunteers had kept a lookout for hostile groups. They were able to warn the serfs ahead of time, and as the battle started, they struck the retinue in the rear. Surrounded by the rebels, their morale quickly wavered.

The Situation Abroad

Around the time of their first proper victory against the forces of the aristocracy, the rebel’s allies over across the sea had suffered a major defeat. The combined forces of the chancellor, along with his ally

Czylle ven Mierholz, had managed to defeat the Ausselian forces at the

Battle of Neittinge.

After the battle, the Ruekish forces decided to pull back their army and to return home. They feared that they lacked the manpower to successfully achieve their goals and hoped to bring in reinforcements for a renewed invasion. At the time the decision to return home was made, the Ruekish forces in Aussel were unaware of the uprising that had started back in Nordhei.

Following their victory in battle, the rebels chased the fleeing soldiers back to whence they came, looting and burning every estate they came across. As their flames engulfed building after building, word of their achievements had spread, but troubling news had reached the rebels as well.

Too bloodied to continue the fight abroad, Kilas III had sailed back home and his forces has returned to the homeland. It was only a matter of time before the armies of the chancellor would come hunting for the insurgents in the countryside. While the ravaging of the estates had brought in fresh blood to bolster the ranks of the rebels, the news of the army’s return soon reversed that trend. Many of the rebels feared they were ill-prepared to face a proper army.

Tomorrow we face our greatest foe, the eternal enemy that has kept us in chain expecting us to stay obedient for generations. Even if we perish in the fight ahead, know that you’ll die as free men and god will award you for such bravery in this quest for a better tomorrow!— Heins of Gilbrenen, 1540

Slaughter of the Serfs

Chancellor Kilas III and his ally, the Duchess of

Valleren, learned of the rebellion upon their arrival. Outraged by the incompetence of the local nobility and their inability to deal with the threat themselves, he summoned them all to

Eekberge. After mocking and berating them for an hour and a half, he demanded control of whatever was left of their soldiers so that he could finish off the insurgents that were ravaging the countryside.

Heins of Gilbrenen and Odo Wudiger, the key leaders of the uprising, feared that by avoiding the army for too long, it would be allowed to grow too strong and that their only hope was a quick and decisive assault. The rebels prepared an ambush, using the snow to conceal themselves as they waited for the enemy to approach. Expecting an ambush, the chancellor ordered his cavalry to stay far in the rear. That way they could charge and save the chancellor’s forces from potential encirclements.

The cavalry had stayed so far behind that it was nearly impossible to spot them from where the rebels were observing the marching units. Their hearts filled with a deadly mixture of passion and fear, they charged from their hiding spots and descended upon the Ruekish soldiers. As soon as their forces had clashed, loud horns blew from within the ranks of the chancellor’s men.

Moments later, the distant sound of a hundred hooves frightened the serfs. A few realised what was about to transpire, and they fled the field of battle. The others who were too blinded by their rage kept fighting, but their spirits were broken as the lancers inflicted dozens of casualties, even killing one of their leaders, Odo Wudiger.

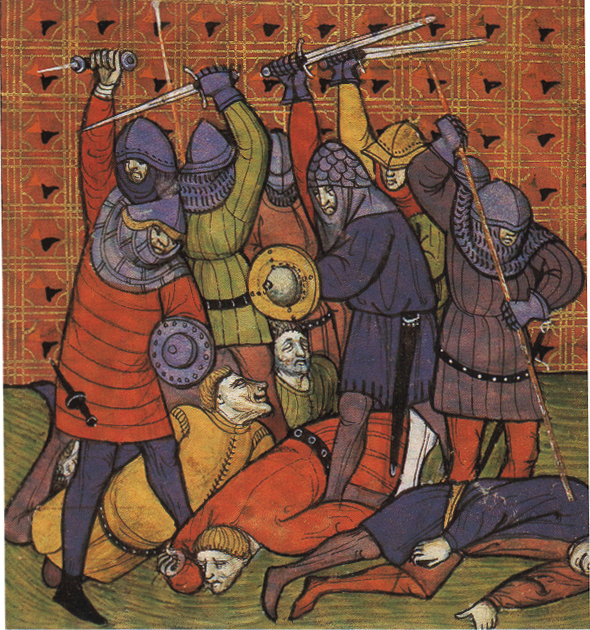

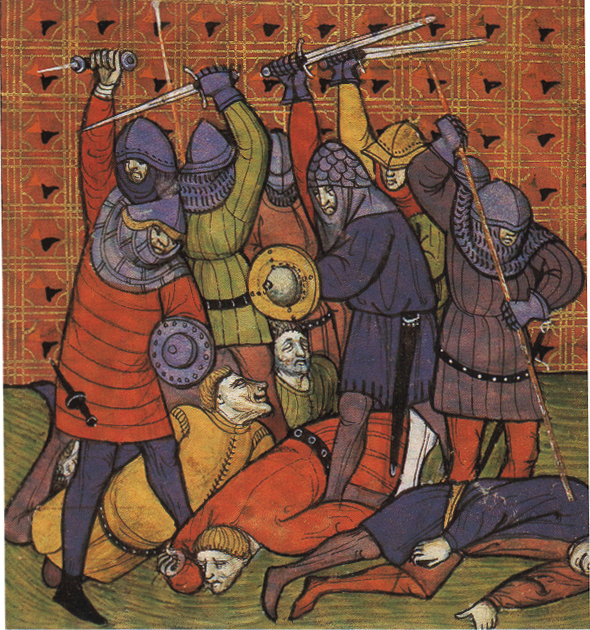

by Ms Roy C VII in the British Museum

End of an Uprising

Following their crushing defeat against the chancellor’s forces, the serfs had no hope of recovery and success. Most of those who had taken part in the uprising either returned to their homes or went into hiding.

Those whose hope had remained undying continued raiding the countryside and fighting the aristocracy, but they were all eventually hunted down.

The last rebel was captured and brought to the capital on the 17th of Bricteril 17, 1541 AA, where he, along with a few other prisoners, was publically executed. His death marked the official end of the Nordhei uprising.

Nice article! It was interesting to see the serfs use the war to their advantage, a shame that the troops returned earlier. In the aftermath section you mention that some changes were made to the rights of the serfs afterwards. What are the things that have improved for them after these changes?