1795

The Jay Treaty is fully ratified, inflaming tensions with France. France’s Republican government recalls its ministers from America in protest. Britain begins submitting rumors and propaganda against American officials, claiming to be in league with the French Republic, particularly those who were against the treaty. Homeland Secretary Randolph is hit hard, as it is revealed he moved to undermine American, and ultimately King Henry’s, governing competency and seemingly taking bribes from the French Republic. Randolph resigns in disgrace, and Hamilton further ties the ideas of Republicanism to French allegiance.

Southern states grow resentful of the treaty, but Hamilton is able to convince many that major political opposition is directly funded by the French to undermine American sovereignty, though the impact is marginal. This, coupled with France’s abolition of slavery in their constitution begins to sway southern opinion to anti-French. James Madison’s control of the Republican Party begins to wane as his stance of anti-Jay Treaty, pro-French revolutionaries, and defense of the institution of slavery become cemented as party platform.

An abolitionist segment of the Republican Party, being known as the Liberty or Libertarian Party, begins to take form.

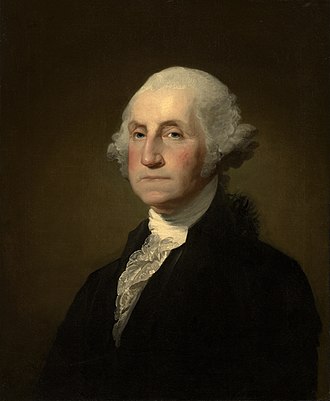

The treaty solidifies a border between the American Kingdom and the territory of Upper Canada. With the removal of British forces from the Northwest Territory, King Henry appoints a delegate to the Indian Confederacy, informally recognizing them as an independent nation. Opposition is fierce to this decision, as it is believed it would disrupt settling of the area. Supporters argue it is necessary to avoid another war. Chancellor Washington orders governors to the rest of the territory.

Hamilton resigns his position as Secretary, though remains a prominent supporter of both the Chancellery and the Monarch, writing essays and speaking lectures.