Ikaharinese Writing

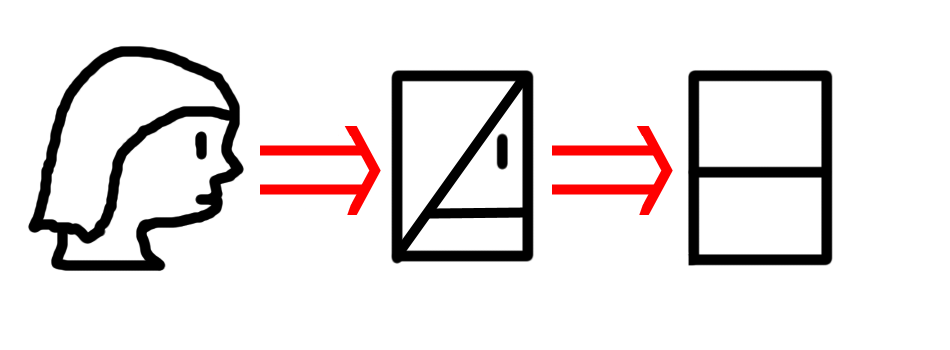

For better or for worse, the only way to write

Ikaharinese Writing, known natively as Shiuitannare, is the only (fully developed) writing system in existence, having been used and refined by the urban societies of Ikaharin for at least 1500 years. It is a logosyllabic script, meaning there are characters for both syllables (syllabograms) and concepts (ideograms).''Oh youWritingDivine toolGreatest giftEnabler-How lost would we beIn ignorance's graspWere you to not be?How would we keep records?Would the future hear us?Could teaching even work?Wouldn't we be like nir?''-excerpt from a poem

History

Origins

''There was once a wise story-teller, the wisest, in fact. Anrin was his name and he knew all the tales ever told by man and god alike, being able to both recite and interpret their millions of scenes and verses without making any mistake at all. Such was his talent that great Iceri, praise be upon her, heard of his prowess and wanted to see it for herself, always being fascinated by humans. Thus she went down to Earth to see him tell his countless tales. Anrin was such a great performer that he made her cry tears of joy, causing her to be greatly impressed. To reward him, she granted him a wish, asking him what he wanted the most in this whole world. His answer was merely that he wanted to have a means to record all his stories so that people in the future would be able to enjoy and know of his work, even if he was roaming Akaina. After much thinking of how to fulfill his request, Iceri invented writing and gave him that wisdom, turning him into the first scribe''.Even if this is how most people (read 'commoners') assume the Shiuitannare came to be, thanks to divine intervention and a particularly wise person, it is most likely not true. The region's historians nowadays argue, instead, that the script started as simple drawings which were used by the earliest bureaucrats to make inventories and record transactions.-myth about the invention of writing

The Great Standardization

''One of the best things I ever did, and one most people don't even thank me for, was to standardize the script, to create a single list of characters and eliminate all ambiguity. Those who may read this and not realize why I think it was such an important and necessary thing to do would be wise to keep reading, for I have an anecdote that perfectly illustrates my point. It was a warm summer night, the gardens' perfume inundated my office, tempting me (in vain) to stop working and go down there. I was signing important documents, nothing unusual, until two of my ministers rushed through the door and into my workspace. Apparently they could not decipher what I meant in one of my edicts. One argued that I had ordered the decapitation of a man in the provinces, while the other said I had ordered his release. As the character I used for the verb could be read as 'cut the head' in a part of the empire and as 'cut the chains' in another, they were confused and scared of giving the wrong order. That I could understand, had they given the wrong command I would have imprisoned them, and I would have made sure that the character in their execution order could only be interpreted as 'behead'. If you, dear reader, don't understand now why I needed to create a single writing system where there could be no double meanings, I am surprised you are able to read this document, as someone as stupid as you should be illiterate''.As the use of the Shiuitannare became widespread, it became able to express things more complex than inventories, with many characters for abstract concepts even being made. However, as the region was (and still is) divided into a patchwork of feuding city-states and there never was an 'official' set of characters to begin with, the scribes of each settlement were essentially free to do as they wished with the script, modifying the signs, changing their meaning and sometimes even replacing them with their own personal inventions. Over time, this lead to a situation in which the people of an area could have considerable difficulty reading something written elsewhere, with countless double meanings and local logograms making it a hard task for many. This lasted until Iter Laku Soksau unified the whole of Ikaharin and realized it would be impossible to run an empire if every province in it had its own way to write and interpreted his edicts as it wanted saying things like:-excerpt from Iter Laku Soksau's biography

''Well, this is how we read it here. If you really wanted us to pay you taxes you should have learnt how that is written here''.In order to end the confusion, the emperor ordered his most important scribes to gather and create a list of universally accepted characters with their meanings and syllabic values, as well as a guide on how to properly use them. After much work and imperial intervention to make the scholars agree with each other, the committee's work was finished and ready to be presented to the world. Luckily, this unified script was a remarkable success, regional styles falling out of use.

A small inconvenience

Features

Ideograms (Annan)

''Oh, my child! How can't you see the meaning of this character? It is extremely obvious, I'd say...''Mostly used for formal things, such as writing official documents, inscriptions in monuments and personal names, the Shiuitannare has thousands of logograms, collectively called Annan, although only a fraction of those are commonly used. It should also be noted that all characters in existence are based off some sort of drawing, mnemotechnic device, rebus or a combination of those.

Modifiers and composite characters

''To write a text using nothing but raw ideograms is as stupid and incomprehensible as building a house out of leaves''.As no ideogram on its own can represent an adverb and there are barely any for adjectives, the scribes deemed it needlessly complicated to invent brand new characters for nominalized/verbalized words and the logograms can't represent details such as verbal tenses or plural nouns, there are several so-called 'modifiers' which allow people to write coherent texts without using syllabic characters. On a somewhat related note, combining and/or tweaking simpler characters in order to make new ones with another meaning is fairly common, as, in the words of Iter Laku Soksau:

''What need is there in making everything more complicated and difficult to learn?''

Easy logograms

''This is clearly a person! It has 2 arms stretched out, 2 legs on the same position and a head on a neck. It couldn't be clearer''.These are the Annan that are similar enough to their base drawings to be readable by people who are either illiterate or have very little knowledge of Ikaharinese Writing. It should also be noted that the easy logograms are always 'raw ideograms' which represent very basic vocabulary.-teacher

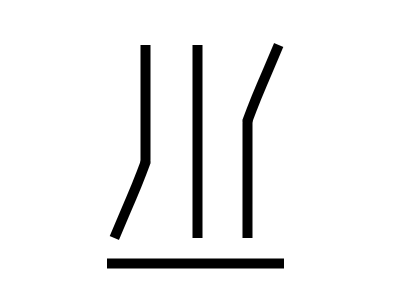

Difficult logograms

''The character for change is extremely straightforward and logic once you think about it enough! Don't you believe me? Well, let me show you. First, you see there are three vertical lines, right? Well, you also see how they are different, right? Good! Now, you also see there is a line at the bottom, don't you? Well, great! That stripe indicates this is an action taking place in time. So... What do we get? Exactly, we get that those 3 strokes actually represent the same object, just that it is changing over time. To put it in a sort of story, Mr. Line is looking to the ground, but then he decides to look to the wall and then to the sky, thus changing his position''.These are the thousands of Annan that are essentially unreadable to beginners and illiterate people, be it either because they are too different from their base drawings, use some mnemotechnic device which has to be explained or are based on a rebus reading in a dead language. Despite Iter Laku Soksau's best efforts, these greatly outnumber their 'friendly' counterparts. Although they are impossible to decipher for most people, some specially talented scribes can guess with some accuracy the meaning of an ideogram they have never seen before.-teacher

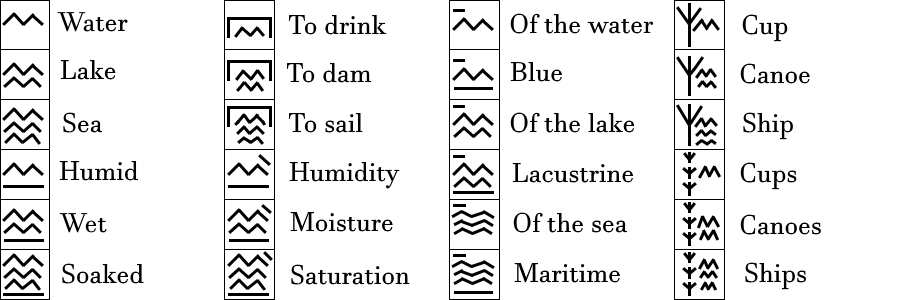

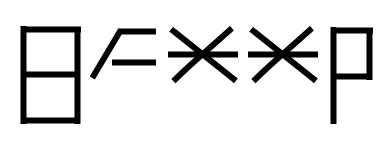

Syllabograms (Daunnar)

''-I don't have the time to play this goddamn guessing game! Can't you just stop messing with me and write the script in something I can understand? -Oh, c'mon, are you going to tell me you can't read these characters? They're literally the easiest ones! Even a good-for-nothing farmer could read this thing! -Cursed be your names! Why do I even work for you?''A much simpler and easy to learn alternative to the logograms, people in Ikaharin also use a syllabary (called Daunnar) to write things down, even if it is only used in informal settings and its use is frowned upon by some elites who think they are 'irhotannare' (peasant's writing). Although the Daunnar and the Annan look exactly identical, as the former were copied from the latter, it should be noted that there are only around 100 syllabograms, which is less than 1% of the amount of ideograms in existence. All glyphs represent either lone vowels (of which there are 6) or a consonant followed by a vowel, and their phonetic values are based on the Shiuihikane reading of their corresponding ideograms. A few examples of this include:-conversation between a playwright and one of his actors

- The syllable 'a': It is written with the same glyph as 'person', because in Shiuihikane it is pronounced 'ahin'.

- The syllable 'ha': It is written with the same character as 'tall', as it is pronounced 'hal'.

- The syllable 'de': It is written with the same character as 'tree', as it is read 'den' in the language.

- The syllable 'ry': It shares its glyph with 'to drink', as that is said 'ryen' in Shiuihikane.

- The syllable 'e': It is written the same as 'woman', as that ideogram is read 'erin'.

A small inconvenience

''-Why is writing consonants with this thing so annoying! It's almost as if the scribes didn't realize our language is full of them... -If they were to have done that, they would have needed many more characters, and the objective of 'this thing' is to have to remember as few symbols as possible, so stop complaining and do your spelling exercices, hopefully with a handwriting I can understand''.Since the Daunnar only only allow for (C)V syllables and Shiuihikane, the language most things are written in, has a more complex (C)(C)V(C) structure, people have had to come up with a way to bridge the gap in order to weave coherent texts. The most popular solution to this issue has always been using 'ghost vowels' for consonant clusters and codas. With this system, all someone has to do to represent a cluster or coda is to write the syllable that combines the consonant in question and the vowel of choice,generally 'a'. For example, 'Daunnar' is usually written 'da-u-na-na-ra', 'Andrin' 'a-na-da-ri-na' and 'Haldenharin' 'ha-la-de-na-ha-ri-na'. Another problem is that vowel length is not represented and the script is only designed to represent Shiwihikane's (rather small) sound inventory, which means other languages sometimes struggle to use it.-teacher chastising student

Calligraphy

''My handwriting is not bad! It's just a very subtle and artistic personal calligraphy! So it's not my problem that you, uncultured peasant, cannot read my poems...''Even if there is a universally accepted standardized way to draw all characters in this writing system (the one that has been showed all across this article), calligraphy is a fairly popular artform among the region's intellectuals, most scholars having their unique style. As these styles often differ greatly from both the official way to write and each other, it is often impossible for the untrained eye to read most calligraphic inscriptions, especially the more 'artistic' ones.

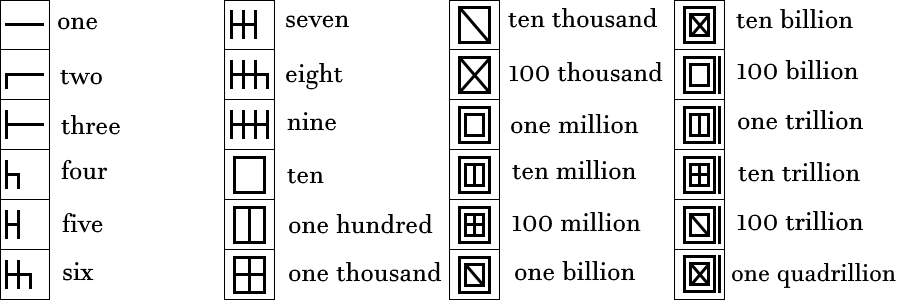

Numbers

''-Why would anyone ever want to count to a quadrillion? I doubt there is a quadrillion of anything anywhere! -One quadrillion is the amount of times you will have to write 'I will not make stupid questions' if you don't shut up and do your exercices''.People in Ikaharin use a series of 24 numeric characters to count and do their calculations. Despite there being characters for a range of numbers up to a quadrillion, this system is rather limited, as it can't represent decimals and can be rather unwieldy at times (especially when it comes to doing complex mathematical equations).-teacher chastising student

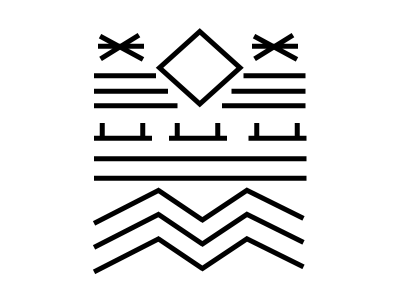

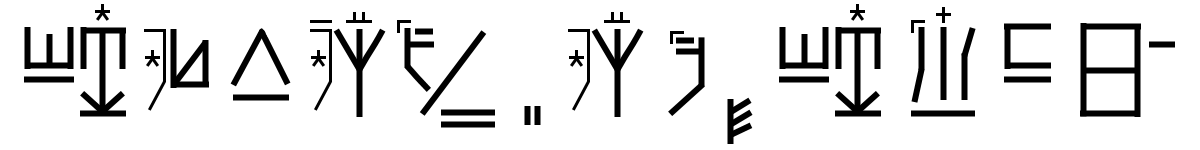

A Text in Annan

''Iter Ennau Ickai aluwan ky Ical Hananden kyemmar maluwan. Ical Hananden sunaemar, no Iter Ennau li nuwemar cer oneman''.-romanization of the Shiuihikane text

''Our Judge Stone house of Mr. Treetop ordered demolished. Mr. Treetop pleaded, but Our Judge no changed his word''.-Word by word translation of the text

''Our Judge Stone ordered the house of Mr. Treetop to be demolished. Mr. Treetop pleaded, but Our Judge did not change his opinion''.-Proper translation of the text

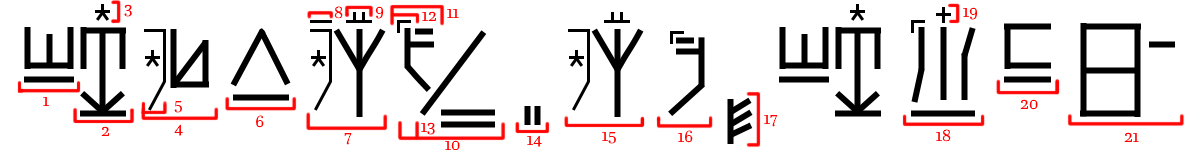

Analysis of the text and its characters

This text uses several characters and modifiers, which have been numbered and will be explained in the list below:- 1: Our (iter). It is a duplication of the character for 'I/me' with an understroke to indicate it is an adjective. Furthermore, the character for 'I/me' is derived from a drawing of the locals' body language.

- 2: Judge (ennau). It is a combination of the character for 'to judge' and the modifier for 'person', which serves to indicate that this is talking about someone who administers justice. The verb glyph was originally a character for 'palm tree', as in an older language it sounded very similar to the word it now represents (in fact the character is no longer accepted as representing that tree and there is a new glyph to symbolize it).

- 3: Person (modifier). In this context it indicates this is a judge and not 'to judge'. It is a reduction of the symbol for 'person', which derives from a stylized drawing of a human being.

- 4: Stone (as a surname) (Ickai). It is a combination of the sign for 'stone' and a modifier that marks this is a family name. The noun glyph comes from a stylized drawing of a rock.

- 5: Surname (modifier). It serves to indicate the character it is attached to is a clan name and not anything else that may be confused with it. It was created by adding a stroke to the person modifier.

- 6: House (aluwan). This ideogram comes from the simplified drawing of a house. Although it should be noted that modern houses in Ikaharin have flat roofs (unlike the one represented in the character), so that original sketch must have been quite old.

- 7: of Mr. Treetop (ky Ical Hananden). This ideogram is fairly complex, and combines element 5, with the character for 'tree', a possessive modifier and another modifier to indicate it is 'treetop' and not just 'tree'. The glyph for 'tree' derives from a stylized drawing of one.

- 8: Of (ky). The possessive modifier marks that the object, in this case the house, belongs to the character it is attached to, in this case Mr. Treetop. Modifiers lack any known etymology and seem to have been either created or consolidated by Iter Laku Soksau's committee.

- 9: Top (hanan). This symbol is placed on top of the one for 'tree' to form the word 'treetop' and comes from the glyph for 'mountain' (which itself is derived from the very stylized drawing of a mountain).

- 10: Ordered to be demolished (kyemmar maluwan). This compound character is formed by the combination of the glyphs for the adjective 'demolished' and the verb 'ordered'. Scribes tend to write participles in the same glyph as the verbs they accompany, as they view them as part of the same thing.

- 11: Ordered (kyemmar). This glyph is made up of the verb 'to order/command' and a past tense modifier. The verb sign ultimately comes from the drawing of a person sitting in a throne giving an order (the detached line representing speech).

- 12: Past tense modifier (-mar). This is a simple modifier that marks the verb it is attached to is to be read in the past tense.

- 13: Demolished (maluwan). This symbol is a participle made by combining the sign for 'the demolish' with an understroke to indicate it is to be read as an adjective. This verb character was created by removing a line from the one for 'house', which the scribes thought would give the reader the idea that the house was being dismantled.

- 14: . (.). It is a punctuation sign which lacks a real etymology, although some say the stroke on the left serves to 'close' the previous sentence and the one on the right 'opens' the new one.

- 15: Mr. Treetop (Ical Hanaden). Without element number 8 this glyph just means 'Mr. Treetop'.

- 16: Pleaded (sunaemar). This glyph is made up of the verb 'to plea/beg' and a past tense modifier. The verb's logogram derives from a drawing of someone sitting in an inferior position begging to someone above them.

- 17: But (no). This character's origins begin as a rebus, as the Shiuihikane word for feather (nol) sounds close enough. In order to avoid confusion between the two, though, the scholars changed the orthography of the symbol for 'but' a bit (by changing the amount of diagonal strokes from 4 to 3).

- 18: Didn't change (li nuwemar). This verb is written by combining the past tense modifier with the negative modifier and the character for the verb 'to change'. The verb symbol's origins start as a rather convoluted mnemotechnic device.

- 19: Negative modifier (li). This modifier, derived from the character for 'no', indicates that the action described by the verb did not take place. The origins of the character for 'no' can be found in the locals' body language, as crossing one's arms/hand/fingers in that fashion means that.

- 20: His (cer). It is a rotated version of the character for 'I/me' with an understroke to indicate it is an adjective.

- 21: Opinion/word (oneman). This glyph is ultimately derived from a drawing of a head saying something (which is represented by the unconnected stroke at the right). Back during the days of the Great Standardization, a few argued that only the unconnected stroke was necessary, but most scholars thought that doing so would cause much confusion and make the character impossible to decipher.

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Excellently done. The explanation about the origin and evolution with its use is on point. You can clearly tell you've done your research with this. Seriously an excellent article I hope you share around =3

Thank youuu! I will do my best to share it :3