Mira in-Maherat, the "Matron Saint" of Coffee (/mɪ.'ra in.ma.he.'rat/)

Mira in-Tanaat (birth name)

Dearest Mira, You've always had a heart for those less fortunate than you, even for those who most people in this world won't give a thought to at all. It's the loveliest aspect of your character, aside from your genuine curiosity about everyone around you. These are both reasons I worry about you so much these days. You're so well traveled these days that I'm not always sure where my letters should find you, so I've sent this to that coffee merchants' guild in Andaen in hopes they know where you're staying these days. I hope you're not staying in Andaen, though I suppose it's safer for you than Kailrana is right now. Azar came by the other day with his latest shipment. He had plenty of time to chat—after he was done fending off complaints, anyway. Only two sacks of beans in his cargo this time. Says there's nothing he can do, that shipments will continue to be disrupted as long as the unrest in Tel-Adragar persists. Is it true that Kailrana deployed another itbaqaan, with those powder weapons and everything? He also told me about your latest advocacy efforts. They're the talk of merchants' circles all over. I really admire all that you do, Mira, but please, be cautious if things get worse. I know you've never been good at keeping your head down, but I'd like you to at least keep it on your shoulders. Ashes, I'm getting worked up just from writing this down. All I'm saying is I hope you stay safe out there, and I'm looking forward to hearing all about your travels again. Write back soon. I'm at home, as always. Safe travels, HounehMany might find it hard to believe that the internationalization of the coffee trade, by far the most lucrative business in Vast Takhet, owes its success in large part to an outsider to the region. But Mira in-Maherat (born Mira in-Tanaat), a merchant’s daughter, accompanied her father on frequent visits to Andaen, Kailrana, and Takhet from an early age. Her frequent travels, curiosity about the world around her, multilingual upbringing, and sometimes stubborn independence all set her on a path to help revolutionize the economy of a subcontinent. But the greedy ambitions that these economic opportunities attracted marred her legacy, and her activism to reverse the resulting harm was tragically cut short.- personal correspondence with Mira in-Maherat,

est. the autumn of 4077 HE.

Early Life and Education

Mira in-Tanaat was born to a Haifah merchant and a Saukkanese mother of uncertain background in the Bay of Maherat, a week’s eastward sailing from the City of Andaen. As with other individuals raised in small fishing villages in the Haifatnehti Basin, she grew up with the family name in-Tanaat, by far the most commonplace moniker across the region, a circumstance which caused her some frustration once she grew old enough to accompany her father, Mathir, as he did business in the Basin’s larger cities. The story of Mira in-Tanaat’s mother, Danira, remains a mystery even to the most determined biographers. Danira was a stoic, quiet woman content who was clearly content to live a quiet life, for interviews with her fellow villagers only revealed that she was always taciturn when asked questions about her life before she married Mathir. Interviewees did make note of Danira’s apparent strength and tenacity, seeing that she did not find gardening or performing home repairs strenuous even in the height of summer. Other, perhaps less reliable accounts note that during an episode in which the village was extorted by brigands from the Saukkanese highlands, her household curiously did not come to harm. Possible explanations range from her successfully negotiating with the brigands in their native tongue to intimidating them, fighting them off, or using more lurid means to dissuade them; speculations about her former life are equally wide-ranging, with some of her neighbors claiming she must’ve been a brigand herself once. Whatever Danira’s true nature and background might have been, she seems to have passed on her stoic tenacity to her daughter Mira. Mira first accompanied her father, the only merchant from their village, on a business trip when she was only twelve years old—after having spent a full year, some accounts claim, wearing down his objections with her insistence. Young Mira could hardly be blamed for this, however, given that she likely grew up listening to her chatty, gregarious father’s sometimes embellished stories of fascinating encounters with city folk and travelers from across the Continent. Having grown up thoroughly bilingual and inherited her father’s social skills, Mira quickly proved to be an indispensable asset to the family business as she rapidly internalized the local Andaeni speech and mannerisms (and suppressed her own Maherati accent), putting customers at ease and even smoothing over interactions with new business partners. She also proved to be a quick study when good fortune enabled the family to have her tutored in reading and writing; childhood friends from her home village have said she was eager to be able to read all the signs in Andaen, and as her literacy advanced over the years, her father didn’t mind having a second eye to review contracts for complex transactions. Further, her father grew more comfortable with the idea of his daughter accompanying him after observing that she seemed decidedly disinterested in boys her age and older. Soon, the father-daughter pair’s business trips became a twice-a-year matter, taking Mira to far-flung ports beyond Andaen. When Mira was seventeen years old, during another stay in Andaen, a booking conflict over their lodging in the Sojourners’ District landed them in a more questionable boarding house near Northharbor, where Mira overheard a group of porters conversing in a language she didn’t comprehend, arousing her curiosity. After befriending the porters and spending an entire evening playing card games with them, she resolved to learn more about their homeland and even visit it someday: A city-state, whose name she couldn’t yet pronounce, on the coast of Takhet. Mira found her opportunity two years later, when her father sustained a serious knee injury from attempting to lift a crate of his goods without the help of Mira or her younger brother Hezman. As their village depended on her family to transport and sell mother-of-pearl and woven Saukkanese crafts abroad, Mira took it upon herself to make what she said would be a “quick” trip to Andaen, insisting that Hezman stay home to watch over their parents. (Hezman had grown up to be something of a homebody, finding satisfaction in pearling and being doted upon by her mother while the rest of the family was away on business.) Her mother did not object, and Mira eventually overruled her father’s objections once again. So it was that Mira arrived at the same boarding house she’d visited two years before—and as soon as she completed her sales and forwarded the proceeds to her family via courier, asked the first Takheti sailors she could find when the next ship was leaving.Personal Life

Mira’s father was known to have mixed feelings about having sponsored Mira’s literacy lessons, having received word of her initial deception by post yet also finding himself eager to read about Mira’s travels. It was much the same for many of her childhood friends and former neighbors, for whom hearing the news of Mira’s latest exploits read out loud to them was a much anticipated—and suspenseful—semi-annual event. Her mother, meanwhile, appears to have tacitly supported her ventures, while her brother Hezman mainly occupied himself with attending to matters at home and later settling down with a family of his own. Years after Mira established herself as a representative of Takheti clans’ and women’s interests, Hezman is known to have briefly involved himself in the family business, but apparently Mira and her father were the most numerate family members. Being that Mira remained single for her entire life, biographers have frequently speculated about her sexuality, with the most lurid and sensational accounts claiming she had any number of female, often Takheti lovers. Comparatively cool-headed and well-researched biographical works, meanwhile, either suggest that she may have lacked any sexual or romantic interests, or else insist that this matter remains unsettled. Mira’s extensive personal correspondence does not provide any direct evidence of romantic relationships in her life, though no small number of biographers have taken it upon themselves to “read between the lines” in her exchanges with several of her long-time friends in Takhet, Kailrana, Andaen, and most improbably her hometown.Career

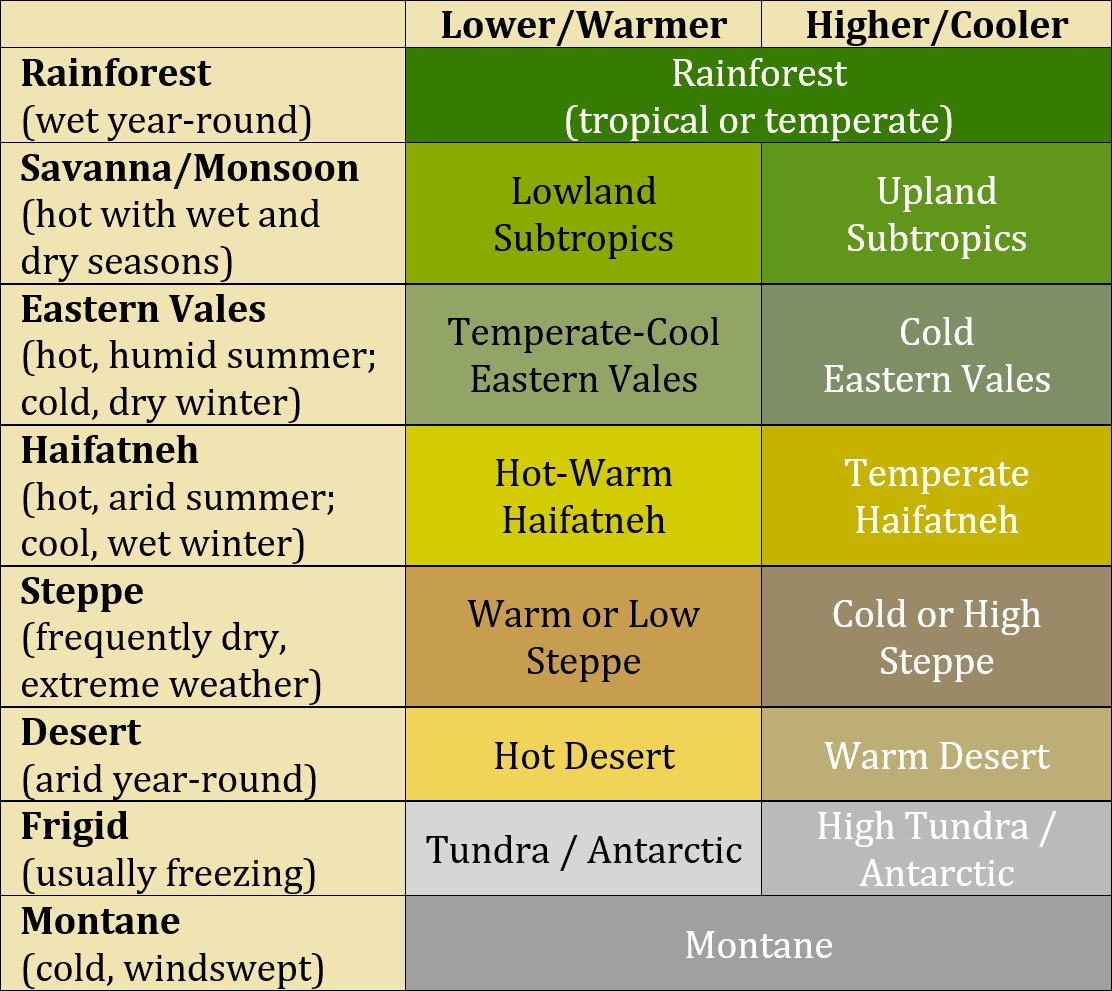

Mira’s entrepreneurial youth would not be without its setbacks. At the age of nineteen, Mira boarded a ship for free passage; earning a free journey aboard a ship in exchange for assisting its sailors in their work was not an uncommon practice. To her disappointment, however, the ship stopped in Kailrana, well short of landing on the Takheti coast, due to unforeseen shortfalls in its captain’s revenues. Nonetheless, this would prove to be more an opportunity than a setback for her, as Kailrana’s mixed Takheti-Haifah population and multilingual environment offered as good a staging ground as any for her to develop her fluency in several Takheti dialects. The docks of Kailrana offered decent work opportunities, too, through which she could raise funds for her next voyage.Mira made a point of integrating herself with Takheti dockworkers and soon observed that the vast majority of them were men, unlike Haifah sojourners whose gender roles were only minimally differentiated. Her inquiries into this situation led nowhere quickly, however, as both Takheti and Haifah workers had long ago learned to accept each other’s ways as “just the way it is.” She soon concluded that proper answers to her questions would only be found through experiencing Takheti social life for herself in their homeland. Mira quickly built up her linguistic aptitude and gradually accumulated funds for her voyage, paying a significant portion of her humble disposable income to send letters assuring her family of her continued well-being. After nearly a year’s labor, she earned enough savings for a trip to what was perhaps coastal Takhet’s least desirable destination: Tel-Izemin (“the Stronghold of Lions”), the once-fabled birthplace of Zamayiir the Lion but at that time an embattled stronghold with only a loose grip on its surrounding lands. She found herself in a land whose destitution surprised her in spite of her experience with the harbor-adjacent districts of Andaen and the middling economic activity of Kailrana. The men of the villages and towns in Tel-Izemin’s vicinity were frequently preoccupied with the defense of their homelands even when they ought to have been farming and fishing, yet women in these settings, Mira realized, were often still relegated to domestic roles. This social world was almost wholly alien to Mira in comparison to her Haifah cultural context, in which women were only sometimes inhibited from taking up entrepreneurial and martial roles. Mira used her sparse funds to set herself up as a middleman for goods passing through the port towns near Tel-Izemin, a context in which she could at least occasionally do business with wives and mothers who shopped for household goods. This, too, was an opportunity for Mira to familiarize herself with Tafayiiri, the Takheti dialect common to Tel-Izemin and several nearby holds. Her information-gathering in this role soon led her to a village in the foothills that was mainly inhabited by women, such were the depredations and casualties it faced. (This village remains unnamed in Mira’s personal correspondence, likely because she chose to protect the identities of its inhabitants.) Despite this village’s troubles, however, Mira discovered upon her arrival that the villagers were cheerful, energetic, and chatty amidst their considerable labors of providing for their community’s sustenance and maintaining its paltry defenses. It did not take long for Mira to befriend these women, and her genuine curiosity concerning their surprisingly positive attitudes toward their circumstances was sated when they introduced her to kahweh, a local brew that, though acutely bitter on her tongue, lifted her spirits. As Mira steadily acquired a taste for the stuff and began to sing its praises herself, one of her new friends in the village told her of a remote place in Tel-Adragar, near the slopes of Takhet Alay, that was thought to have the oldest tradition of brewing kahweh (coffee). Mira scrounged up trail supplies and crude weapons for herself and another young woman, Tidret, who chose to accompany her. A perilous expedition in which the two women may have been kidnapped at one point—a rare episode of Mira’s life about which she was taciturn in her writings—eventually led them to their destination, where horticulturists enjoyed such an abundance of coffee beans that they used the grounds from their brews as fertilizer for the rest of their crops. Surely enough, the brews there turned out to be stunningly diverse in their aromas—and noticeably more potent than those Mira had first sampled. Mira made frequent trips between Tel-Adragar and Tel-Izemin, facilitating exchanges among the villages within those holds and helping their residents sell their beans in Tel-Izemin’s port towns. After she cajoled a few busy merchants and overworked guardsmen into trying her samples, she returned to the villages with what she thought to be only modest returns, yet for the women villagers, these were the largest profits from business they had ever seen. Sometime in 4049 HE, Mira saved up modest funds—only a partial share of the profits, most of which went to the villagers who grew and harvested coffee—and embarked first to Kailrana and then to Andaen, distributing her samples in search of potential investors who could help her villager friends in Takhet scale up their coffee-growing activities. Business for Mira and company was sluggish but not without profits for the first two years. Then one day, one of her samples found its way into an office of the government bureaucracy in Andaen. There, to Mira’s surprise, she found the most urgent demand for a powerful stimulant, as the bureaucrats’ steady, moderate incomes were paired with no small amount of office drudgery that nonetheless demanded alertness and an attention to details. This development promised such momentum for the ventures of Mira and friends that Mira feared the villages she’d sought to befriend would soon be subject to further depredations by outlaws or even petty warlords who hoped to fund their own ambitions. There is a near-decade period between 4051 and 4059 HE during which little written correspondence from Mira has been found, presumably because she and her own built up local coffee plantations and shipped out their goods as discretely as possible; one semi-legendary account claims she would hide sacks of coffee among shipments of aged fish and shellfish, then washed the beans thoroughly and perfumed the coffee sacks once she reached the relative safety of the Takheti coast. One way or another, by the time those first coffee plantations earned their notoriety near the end of the decade, the villages in question were already able to hire trained and armed sentinels, as well as laborers to construct relatively smooth roads for their shipments. The village in Tel-Adragar would come to be known as Igh-Berkaana, and businesspeople and rumor-mongers alike from coastal Takhet to Andaen started referring to Mira as Mira in-Maherat once the destination of a number of her personal letters became known.Coffee and Politics

Initially, Mira in-Maherat had every reason to take pride in having spearheaded the development of unprecedented business opportunities for previously immiserated villagers in Tel-Adragar and Tel-Izemin. Further, as a long stretch of the Takheti foothills offered a similarly hospitable climate for coffee plantations, coffee rapidly became the most abundant export throughout the former lands of Great Wahaareh—even to the point that some horticulturists and agrarians abandoned the growing of cereal grains and orchard crops to join in on Takhet’s new commercial bandwagon. Unfortunately, the attention that was attracted by the flow of trade with and investment into these communities was not always wholesome. Ever-growing demand for coffee through a widening area of the Haifatneh Basin, Vast Takhet, and lands beyond fueled increasingly ambitious investments, which eventually produced larger-scale plantations with outsiders as owners and questionable labor practices. (The original plantations in Igh-Berkaana were thankfully slow to become hyper-competitive themselves, likely because they grew a range of cultivars whose diversity had no obvious rival elsewhere in Takhet.) As increasingly larger and more powerful interest groups set their sights on the emergent coffee industry, prime lands for plantations became subject to political contestation, first among Takhet’s own polities and then among foreign powers. Among these predatory foreign powers was the city-state of Kailrana, Mira’s launching point for her illustrious career. Being positioned roughly halfway between coastal Takhet and Andaen, the port city became a key midpoint for the coffee trade, such that its merchants and politicians developed the means to acquire coffee plantations of their own. In the early 4070s HE, Kailrana’s mayor, in collusion with the city’s leading merchants, invested commercial and even military resources into defending the city’s economic interests in Takhet, all the while turning a blind eye to the not-infrequent abuses committed by the latest generation of growers. By this point, Mira had withdrawn from public life, focusing on advising villagers on best business practices while privately blaming herself for the unsavory developments in the coffee industry. “Mira, the Patron Saint of Coffee,” as commentators in Kailrana called her, was not an epithet she welcomed even if it was more or less in jest. A crisis that unfolded in the middle of the decade would compel Mira to break her silence. Although labor conditions had hardly worsened in the plantations of Igh-Berkaana, the plantation workers there were privy to the more dire circumstances of their contemporaries elsewhere in Takhet. With the commercialization of coffee operations in Takhet, they saw the writing on the wall and pre-emptively advocated for the protection of their labor rights. As a great portion of the growing town’s residents had ties to the coffee industry—and were not its barons—a surprisingly large movement emerged in sympathy with the plantation workers. Toward the end of 4074 HE, when the chief of Tel-Adragar responded by turning away a crowd of petitioners at his doorstep, the popular movement stirred up a series of protests, eventually leading to a workers’ strike on coffee production. After the chief tried and failed to use force and other strike-breaking tactics to put the workers back in line, he was pressured into resigning due to his failures. All of a sudden, the coffee-growing capital of Takhet was thrown into a leadership crisis. Once word of this development reached the leaders of Kailrana, they saw an enticing opportunity before them. Claiming a benevolent initiative to protect the commercial interests of their economic partner of Tel-Adragar, they financially supported their preferred candidate for the hold’s new chief: Izmir ja-Amaran one of the hold’s notoriously corrupt plantation barons. Kailrana’s leaders are also thought to have intimated several of their candidate’s rivals into bowing out of the contest. Within months, ja-Amaran and Kailrana’s leaders both got their way, with ja-Amaran undermining a number of labor protections for plantation workers (on the pretense of shoring up Tel-Adragar’s ability to compete with rival coffee producers) and Kailrana’s coffee importers ensured of exclusive trade deals in exchange for their city’s support of ja-Amaran. The situation of Tel-Adragar’s laborers quickly devolved, and this seems to have finally brought Mira in-Maherat back out of hiding. Her letters written soon after the soft coup in Tel-Adragar put her guilt for her (arguably exaggerated) role in shaping the circumstances of Takheti plantation laborers. At the same time, the news of Kailrana’s political maneuvering seems to have reminded her of the results that can be attained through persuasion and backroom negotiations. Mira began to make regular trips between coastal Takhet and Kailrana, assessing laborers’ conditions through fieldwork and then reporting her findings to anyone in Kailrana who would lend her their ear. Even with her considerable charisma and charm, however, Mira found few supporters, and the majority of these sympathetic individuals were themselves poor workers who could make few material contributions to her cause. Between this and the threats she began receiving from more powerful individuals in Kailrana, Mira soon learned that simply appealing to the Takheti laborers’ humanity would have little effect in the city. Months of fieldwork plus Mira’s existing personal connections seemed to have more weight in coastal Takhet. Her travels and information exchanges made clear to one community after another that their waning workers’ rights were not unique but part of a widespread phenomenon in Takhet. Mira’s findings from her conversations with those who resisted abuses of power, too, percolated through the information network that she helped expand there. On subsequent trips to Kailrana, Mira refocused her efforts on fundraising—ostensibly to raise workers’ standards of living, which she was concerned with, but also to support organized collective action groups, most prominently in Igh-Berkaana, who led plantation slow-downs or protested through more discrete means such as smuggling or sabotaging bean shipments to fracture plantation owners’ relationships with their regular customers. Mira’s more forceful labor advocacy backfired on her sometime in the spring of 4076 HE, when she was assaulted near the docks of Kailrana. As she recovered from the particularly brutal beating, presumably carried out by plainclothes enforcers of the interests she fought against, she sent a letter full of innuendo to a friend in Tel Adragar circumspectly explaining her situation and musing that honeyed words alone may not suffice to resist opponents who would so readily resort to force. While the port cities of Takhet generally saw (export-friendly) law and order enforced by cities that could spend considerable portions of their budgets on training and outfitting security personnel, the major plantations at higher altitudes were more remote and vulnerable to banditry. It was here that Mira saw the potential for a more vigorous plantation workers’ resistance movement. Although these places, most notably Tel-Adragar, invested greatly in the defense of their lands and trade corridors as well, the plantation workers knew the lay of the land, as did their allies in the clans of camel-riding herders whose grazing lands were repeatedly encroached upon by growing plantations. Mira and some of her close compatriots in Igh-Berkaana were instrumental to both bridging barriers between the groups’ dialects and ensuring that they could learn from each other, the resistant workers learning the herders’ skirmishing tactics while the herders could better familiarize themselves with the plantations’ patrol patterns and other security operations. If Kailrana was going to use force to get its way, Mira and her compatriots had concluded, then why shouldn’t the numerically superior plantation workers and others who were oppressed by the coffee barons? Limiting the dissidents’ capacity to undertake armed conflict, even skirmishes and whirlwind attacks on coffee caravans, was their inability to afford arms and armor that could match those of the settlements’ and plantations’ security forces. As Mira could hardly fund-raise in either Takhet’s coastal cities (being economically dependent on coffee exports) or Kailrana, Mira braved more hazardous overland journeys past Kailrana—to Andaen, whose leaders once enjoyed the growing trade traffic through Kailrana but were growing wary of Kailrana’s growing reach. Mira was able to play upon influential Andaenis’ anxieties by sharing detailed eye-witness accounts of the excesses of Kailrana and its client-state Tel-Adragar. Although it quickly became clear—to the relief of Mira and all other parties involved—that Andaen’s leaders had no interest in starting a conflict that would disrupt economic activity along the Northern Coast, they did not especially mind that the Takheti dissidents were becoming a growing thorn in Kailrana’s side. As much as Mira felt she was dirtying her hands through her negotiations with Andaeni merchant princes, little different in character than their contemporaries in Kailrana, neither party could ignore their shared interests. It was not long before the movement that Mira advocated on behalf of enjoyed significant Andaeni patronage—including the aid of enforcers hired by Andaeni merchants to aid in the smuggling of weapons to Takhet. Mira made no direct mention to friends and family of martial exploits in the foothills of Takhet Alay, certainly. But in retrospect, rumors of her involvement in Takheti raids may not have been baseless. She would have been far from the first Haifatnehti woman to fight both in defense of those she cared about and on the offensive. Indeed, large numbers of women participated in the Campaign of Reconquest as well as shoring up the defense in the Second Assault on Andaen.Circumstances of Death; Legacy

Letters sent to Mira in late 4077 and 4078 HE take on an increasingly dire tone. The sensational (or not) stories of Mira having personally carried an arquebus and led assaults on coffee caravans did not help matters, nor did the circulation of rumors in high-society circles of Mira’s collusion with Andaeni merchant princes. Oddly, the latter development may have endangered Mira more than the former one: Polities all across the Haifatneh Basin and its periphery were keenly attentive to the political happenings in Andaen, not the least those which also involved the city-state’s rivals. Worse still for Mira, even as tensions between Andaen and Kailrana continued to rise, their commercial interdependence made each city reluctant to close its gates and ports to the other. This is why Mira’s sudden demise, dated to 12 Baarnaa (the middle of autumn), is widely thought to have been the result of foul play. The official explanation for her passing was severe head trauma due to an accidental fall from the busy docks of Northharbor, but what remains inadequately explained is why Mira was found at Kailrana’s chief port of business with Andaen in the first place. It is possible that Mira voluntarily visited Northharbor to meet with Takheti workers there, but this seems to have been an excessive risk for her to take. Andaen has business and high-society quarters both near and distant from Northharbor, and a traveler entering Andaen by land would likely stay somewhere in the Sojourners’ District opposite the city’s oceanic coast. Explanations supplied by biographers of Mira’s life vary. Mira had lived to the age of fifty-two, leading some writers to suspect that she really did meet an untimely accident due to frailness, but this claim seems contradicted by Mira’s extensive maritime and overland travels and her supposed involvement in Takheti insurgent activities. That she might have been found commiserating with Takheti porters around Northharbor is within the realm of possibility, yet her sympathies were mainly with the plantation laborers in Takhet proper, whose jobs and life situations were quite separate from those laborers, Takheti or otherwise, involved in exporting coffee beans. (And certainly, she was shrewd enough to avoid unnecessarily spending time in a place where residents of Kailrana might recognize her.) Alternatively, hired thugs tracked her down somewhere in the Sojourners’ District; these thugs likely brought her to Northharbor, where she met her end through struggle and/or a staged accident. A more sinister theory still is that these thugs murdered her somewhere outside Northharbor and transported her body there afterward. Whatever the circumstances of her death, word did not take long to spread along the extensive trade and communication networks of the Haifatneh Basin and Takhet alike. The immediate aftermath was a flare-up of insurgent activity in Takhet, leading to violent crack-downs and small-scale massacres in at least three instances in Tel-Adragar alone. As revolutionary anger heated up and then died down, early commentators—likely with many propagandists among them—tried to tie Mira’s legacy to this wave of violence, tarring her as an upstart who narrow-mindedly pushed for labor movements’ causes without considering their broader impact on livelihoods and public safety. Takheti leaders’ suppression of this movement seems to have quieted dissent, at least in the short term, yet likely also built up resentment of authority like scar tissue. The resulting oral histories of oppression and resistance would later be alluded to during subsequent generations’ covert or overt resistance movements, most dramatically the Igh-Berkaana Incident. In contemporary discourse and folk legends, however, Mira in-Maherat is still popularly known as the “Matron Saint of Coffee.” This may simply reflect the levity in looking upon past troubles from a distant historical viewpoint. (Among non-historians, a distance of two or three generations is sufficient). Regardless, Mira’s image has been largely sanitized since the heyday of her activism, and even legends of her participation in caravan raids are recounted with tones of heroism and adventurousness rather than suggesting maliciousness on her part. With time, Mira in-Maherat could very well be adopted (or appropriated) as an inspiring figure for future resistance movements, even outside Takhet.

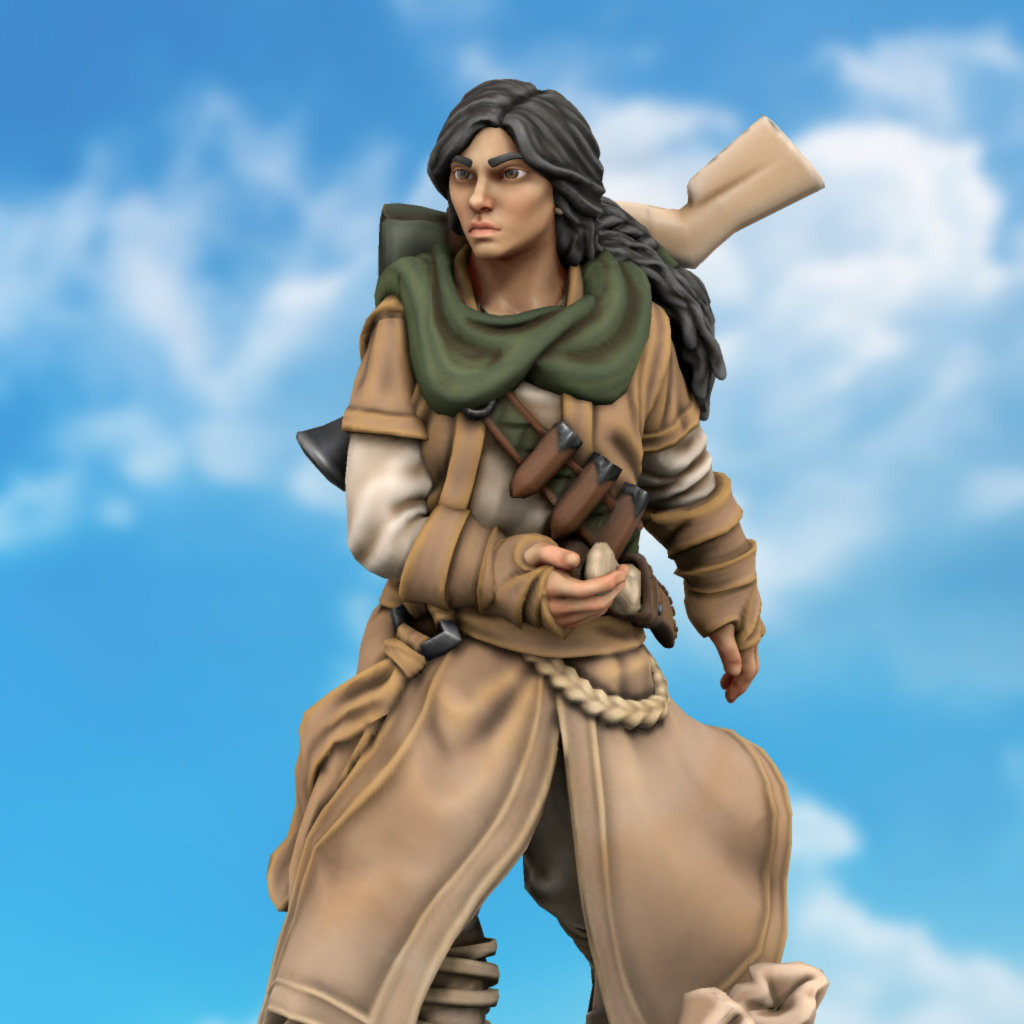

Mira in-Maherat, c. 4076 HE by eldknighterrant

Ethnicity

Other Ethnicities/Cultures

Date of Birth

4 Mashpalu, 4026 HE

Date of Death

12 Baarnaa, 4078 HE

Life

4026 HE

4078 HE

52 years old

Circumstances of Death

not established; foul play suspected

Birthplace

wal-Tanaatu, a fishing village near Maherat in the northeastern Haifathneh Basin

Place of Death

Children

Sex

female

- Haifatmizti (Maheratmizti, Andaeni)

- Saukkanese (Maherati)

- Takheti (multiple dialects from Coastal Takhet and Takhet Alay)

Hi there! Thanks again for allowing me to read your article on stream! Here's the link to the VOD on YouTube. I appreciate you sharing such an interesting character!

Check the latest in the wonderful world of WILLOWISP...

Find out what I'm up to...

Support my creative efforts <3

I sorta feel bad about how long the article is, but thanks so much for reading and airing it out!

don't feel bad! I feel bad about having to skim through it lol. Sorry again. I'm just glad that Summer Camp was very productive for you! Congrats once again on all the words! <3

Check the latest in the wonderful world of WILLOWISP...

Find out what I'm up to...

Support my creative efforts <3