Lafargha, The Embattled Plains

The Plains of Bones Crushed Under Heel

Dusk falls upon the Laewerge again, and with it the Baldaaru flows a double crimson: That of the setting sun, and that of the soldiers who lie slain beneath it.In the Embattled Plains of Lafargha, history has, for the most part, been narrowly defined by geography. By virtue of a favorable environment for growing cereal grains and a proximity to several centers of civilization, the Plains have long attracted attention wanted and unwanted alike. Thus, the voluminous Baldaaru River and the golden fields of grain flanking it are often mentioned in the same utterance as the conquerors who set their eyes upon them; the fertile expanse has long been sown with seeds and fragments of bone alike. The Lafargha (or Laewerge) Plains were a key site of contention at the bookends of the The Internecine Wars. The mouth of the Baldaaru was among the first sites to attract Frulthudii farmers and the colonial-imperial designs of their Reborn Theocracy. By the time the Rebel Coalition rallied the people of nearby Saukkan-Ghat against the Theocracy, the Plains were amply populated by the grandchildren of settlers—denizens through whom the Coalition would cut a bloody swath on their way to Andaen.- Excerpt from the writings of Chelal, former bandit-king of Saukkan-Ghat during the March from Authenwerge. c. 3496 HE.

Etymological notes:

The true origin of the region’s placename remains unknown. Although the name Lafargha is fully pronounceable to speakers of Haifatmizti, pre-Interencine records in Old East Haifatneh Script use diacritics indicating that the first two vowels were not readily pronounceable in the Haifatmizti dialects of the time. Philologists have reconstructed the ancient placename as Lefergha; this is speculated to originate from a language related to those spoken in Saukkan-Ghat, though neither tongue nor script of this sort is historically attested in this region long inhabited by the Sea Peoples originally from the Haifatneh Basin. Laewerge, the placename used by the Reborn Theocracy, is often mistaken for the name of a fortress or citadel due to the apparent ending -werge which appears in the names of several historical strongholds of the Reborn Theocracy. This folk etymology so popular that explorers and archaeologists have excavated old battlefields in the region in search of a Crusader ruin that they insist must exist. However, serious scholars of the history of the Crusade and Reconquest hold that Laewerge is merely a phonetic translation of the original placename in Kraesprauch (-werge from ergha).Geography and Climate

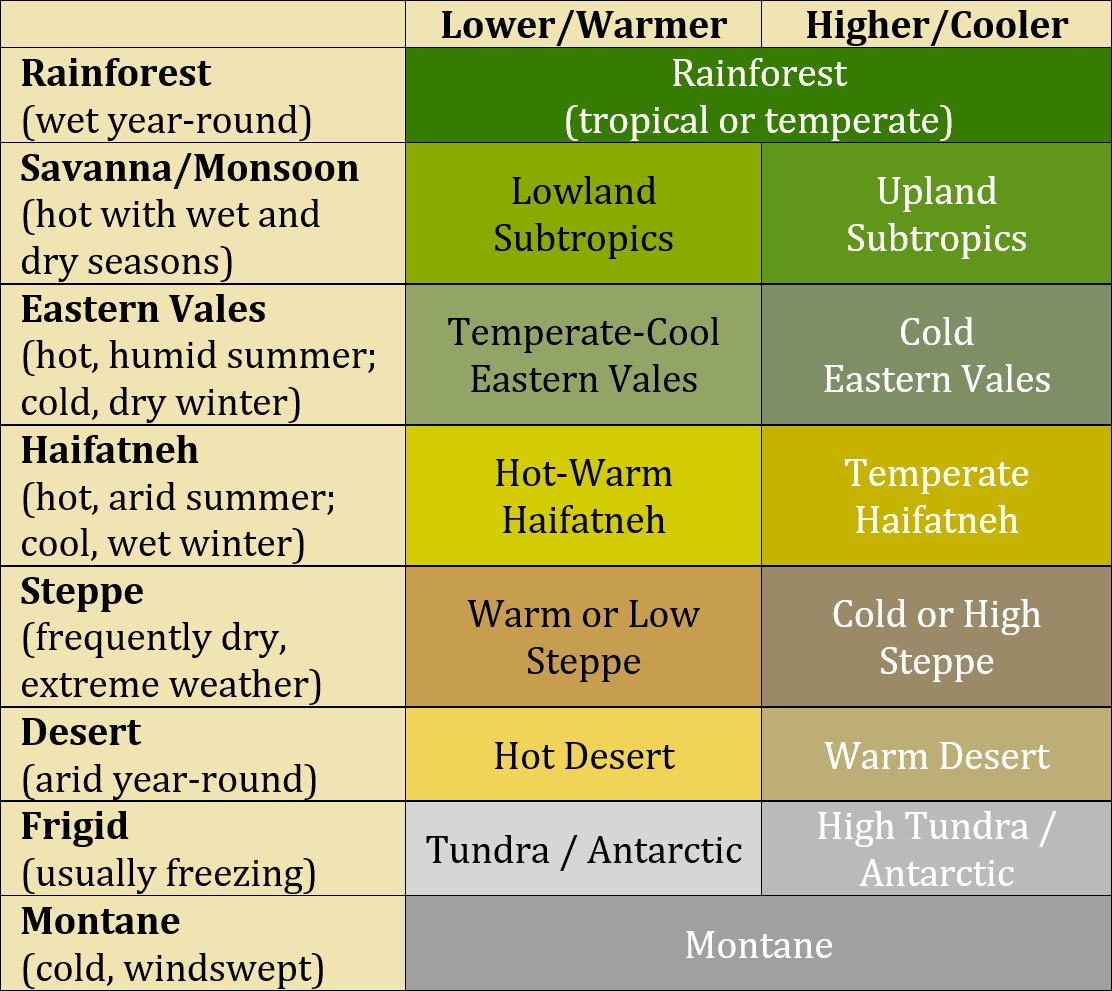

Much of Lafargha is a hot, open lowland with a climate similar to that of the Haifatneh coast, though the northern reaches grow more humid and see more frequent, less predictable precipitation toward the coast of the Boundless Ocean. The plains rise in elevation, first gradually and then rather sharply, as they merge with the foothills of Kanai-Aichit. From those mountains flows the Baldaaru, a voluminous river bisecting the Lafargha Plains. The Baldaaru river valley appears to have been the route through which the pre-Haifah Sea Peoples settled the Plains, perhaps because the region's extensive southern coast is mostly flat and sandy, presenting few places for sailors to anchor safely. Geographers have considered the possibility that the course of the Baldaaru has moved multiple times during the region's prehistory. The mountain range of Kanai-Aichit and Saukkan-Ghat to its east are both known for their exceptionally powerful earthquakes, and evidence of pre-Internecine civilizations in the Plains indicates cultural boundaries and subregional differences in wealth that are surprising given the region's lack of geographical obstacles to travel (aside from the Baldaaru itself).History of Contention

Little-Known Beginnings

Aside from the fact that the Sea Peoples settled the region soon after the first millennium of the Ancient Era, little is known of the region's early in history in part because of the ravages of imperial conquests (and earthquakes—see below). As much of Lafargha consists of an open plain straddling an abundant river, the region is at once hospitable to agrarian civilization and relatively simple for an even somewhat ambitious military power to conquer. So far as the region’s ancient cultural geography has been uncovered through archaeological findings and historical research, subregional differences in wealth and material culture that are evident in the region’s prehistory are surprising given the lack of geographical obstacles to travel there (aside from the Baldaaru itself). Geographers have considered the possibility that the course of the Baldaaru has moved multiple times during the region's prehistory given that the mountain range of Kanai-Aichit and Saukkan-Ghat to its east are both known for their exceptionally powerful earthquakes.Accommodating Empires

The first empires to see the Lafargha (or Lefergha) as a potential breadbasket were two confederations of chiefdoms on either end of the first Saukkanese golden age (roughly 2550 to 2680 HE). While nearby Kanai-Aichit is so high in elevation as to be inhospitable to large human populations, the (somewhat) more moderate altitude and significant runoff of snowmelt in Saukkan-Ghat have made the latter capable of hosting sizable agrarian settlements as well as well-fed nomadic herders. On the few historical occasions that these scattered Saukkanese communities coalesced into polities that spanned the region’s lesser mountain ranges, the next natural barriers to (or targets of) territorial expansion were the Bay of Maherat followed by Lafargha. The subjugated peoples of Lafargha were largely unaffected by the internal disputes that caused the dissolution of the first Saukkanese confederation in the 2580s HE, but the political crisis of the second confederation that unfolded in 2682 HE resulted in a bloody contest among feuding chieftains for Lafargha’s farmlands. This conflict was far more sudden and considerably more violent than the initial Saukkanese conquest of the region, which was gradual and frequently involved Lafargha’s agrarian communities surrendering peacefully to the invaders. The political collapse of the 2680s was sufficiently dire to drive refugees westward across the Haifatneh Strait, where they assimilated themselves into the communities of the Sea Peoples there with some difficulty due to stark differences between the groups’ dialects and customs. Starting from roughly 2740 HE, Lafargha knew relative peace, and its yields of cereal grains and chaana (chickpeas) were sufficient that traders could sail down the Baldaaru, into the Haifatneh Strait, and from there to either the Haifatneh Sea or Shaqhu Isle to the west, exchanging their spare staples for luxury goods such as Haifatnehti pearls and the incense and herbs which occasionally made their way to Shaqhu from faraway Takhet. By 3000 HE, Lafarghit art and political power developed to a sufficient extent to exert their influence across the Strait and even more so in the impoverished coastal plain of Wal-Keshish. It was with distress, then, that pre-Haifah communities of the northern Haifatneh Sea recorded the end of this nascent Lafarghit golden age when an alliance of warrior princes and their grizzled horde followed the banner of Pharish the Sole Chieftain into the Plains. The devastation wrought by Pharish—first his conquests of Lafargha and lands beyond, and then the troubled legacy he left when his generals, formerly the lesser Saukkanese chiefs, fought over the remains of his empire. The decades of fighting that followed—a series of internecine conflicts long before the Internecine Period began—cemented Lafargha’s reputation as a land of serial tragedies.Under the Theocracy

The invasion of Lafargha by the Frulthudii colonists starting in 3422 HE did not appear meaningfully different from the depredations of previous empires—at first. But whereas the mainly Saukkanese conquerors of the past were content to subjugate the inhabitants of the Plains, putting them to work to feed imperial armies and fill imperial coffers, the Frulthudii settlers soon made it clear that they intended to use the land by and for themselves alone. The Reborn Theocracy waged a campaign of destruction and reconstruction across the Plains, displacing or sometimes depopulating entire settlements only for the Frulthudii settlers to rebuild for themselves much of what they had destroyed. Nor did they show any interest in local customs and lifeways, even those which might have helped the colonists adapt to their new environment. When the colonists did spare (and subjugate) the survivors of their invasions, they often made a point of compelling these survivors to forsake their language and their traditional beliefs alike, reeducating them as Kraesprauch-speaking followers of The One Light. It was not until the reign of Rae-Matath Hrauwar beginning in 3456 HE, well after the Lafargha Plains had been fully conquered by the Theocracy, that this largely genocidal approach to settling the Lafargha Plains gave way to less overtly violent assimilationist policies in the Theocracy's frontiers. This shift in policies during Hrauwar's reign came too little, too late as far as the Theocracy's victims and their descendants were concerned; resentment and shared interests grew the numbers of the Theocracy's enemies, and the Rebel Coalition that formed from indigenous groups of the Haifatneh Basin gained momentum. After their shocking success in assaulting the the Citadel of Authenwerge, once the exemplar of the Theocracy's war machine, Saukkanese chiefs who had been impoverished by the Internecine Period's disruptions of regional trade resolved to join the Coalition, and Laewerge was all that stood in their way on the bloody March from Authenwerge to Andaen. The populousness of Laewerge paired with the drivenness of the rebels ensured remarkably large losses of life there; the Baldaaru River ran red multiple times over the course of the six-year campaign. One odd consequence of the Theocracy's early approach to settling Lafargha was that the comparatively dry, sparsely populated Gamarh (now known as Wal-Keshish) to the west of Andaen overtook Lafargha (renamed Laewerge) as the Theocracy's chief breadbasket region for several decades. Put simply, the smaller and more mobile (pastoral-nomadic) populace of Wal-Keshish was displaced by the Frulthudii colonists more quickly, enabling them to establish their preferred agriculture and infrastructures there sooner. In choosing this route of imperial development, it appears the Theocracy failed to fully avail itself to the bounty that the Plains of Lafargha could've yielded for its populace, thus somewhat slowing the Theocracy's further expansion.Long Days of Hegemony

The Rebel Coalition's campaign, led primarily by those who had come to know themselves as the Haifatnehti People, nearly reversed the population shift brought about by the initial Frulthudii settlement of Laewerge. However, in addition to subjugating a considerable number of the Theocracy's subjects—those who were willing to renounce their Bairhanii faith, at least—the Coalition brought in ethnic Haifah settlers from across the Haifatneh Sea. While these "reconquerors" rightly asserted that their cultural and familial ties to the pre-Internecine peoples of the Lafargha Plains were far closer than those of the Frulthudii settlers, the reconquerors' amalgamation of several Haifatmizti dialects and disparate worldviews exhibited little relation to those original to Lafargha. Still, the broad narrative of the Crusade and Reconquest as a reclaiming of Haifah lands for the Haifah people proved to be a popular rallying point for their war effort, securing the view of Lafargha as a homeland finally returned. The reality that the reconquerors constructed for themselves was more important to them than any reality that was occasionally unearthed by ploughs and excavations. That the Rebel Coalition agreed not to establish its own empire during the Treaty of Andaen suggested a route to political independence for Lafargha's new inhabitants, but this hope, too, would be short-lived. Once Andaen was reconstructed as a free city-state, its location straddling the Haifatneh Strait (subsequently known as the Strait of Andaen) ensured for it a central position in the regional order that would arise from the ashes of the Theocracy. The Strait linked the Haifatneh Sea to Vast Takhet and places further afield throughout the Boundless Ocean, making it a critical artery for transregional trade, not to mention exchanges of experts and their expertise. So it was that Andaen would not only grow to be the primary trade hub of Northwest Tahuum Itaqiin but also its intellectual capital, as seen in the unequaled University of the Esoteric Arts and Lore and other institutions. Once Andaen became powerful enough to fend off the subsequent imperial designs of Great Wahaareh and endure the geopolitical anarchy of the Grim Era, it was only natural that New Lafargha, a political and cultural patchwork, would fall under its dominion. From Andaen came opportunity-seekers, up the Baldaaru River in a similar fashion to the Sea Peoples so long ago, first merchants interested in buying land and then armed forces paid with any funds that Lafarghi locals refused. The Lafargha Plains have remained under Andaen's shadow ever since, whether through the city-state's direct control over farmlands near the Strait or through its suzerainty over the fledgling polities that had managed to sprout through the region.

Alternative Name(s)

Lefergha (???? - 3423 HE)

Laewerge (3423 - 3500 HE)

Laewerge (3423 - 3500 HE)

Location under

Related Ethnicities

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Comments