Grape Wine, A Social History of

”Never have I known a taste more bitter than the sweet tang of wine drunk at the behest of my adversary.”Being among the oldest and most popular of human endeavors, grape wine cultivation and production have a history deeply intertwined with the social history of the Northwest. Studying the evolution of wine can offer a detailed if unconventional window into the cultural, societal, and technological changes that have shaped the daily lives of the Northwest’s inhabitants.- General Ishkamet, as quoted in the prose-poem

A General without a King about the Regicide of Baitha.

Lost Histories and Contested Origins

The hot, arid summers and cool (but rarely freezing) winters of the Haifatneh Basin and its surroundings make a virtually ideal environment for vineyards. Certainly, the Basin is second to none in hosting the known world’s widest range of wine grape varietals. The most sought-after vints, disproportionately from the coastal foothills of the Southern Bounds, have been exported as far as the tropics of Au-na-Lai, and wine amphorae have been found among the treasure-laden burials of Golden Steppe nomadic chiefs.Hierarchies of Wines and Drinkers

Thanks to the relative ease of maritime travel across the Haifatneh Sea—during times of peace—viticulture quickly became a feature of urbanized societies and other large settlements throughout the Basin. It is thought that grapes were grown for wine production at least as early as for any other form of consumption, given the ubiquity of beer and ale across the settlements of the Sea Peoples. The perishability of fresh grapes, too, made wine itself a crucial agricultural product. Sun-dried raisins are also widespread in the archaeological record but were a secondary product of lower-quality grape crops or else were produced using non-wine cultivars.Wine and social status

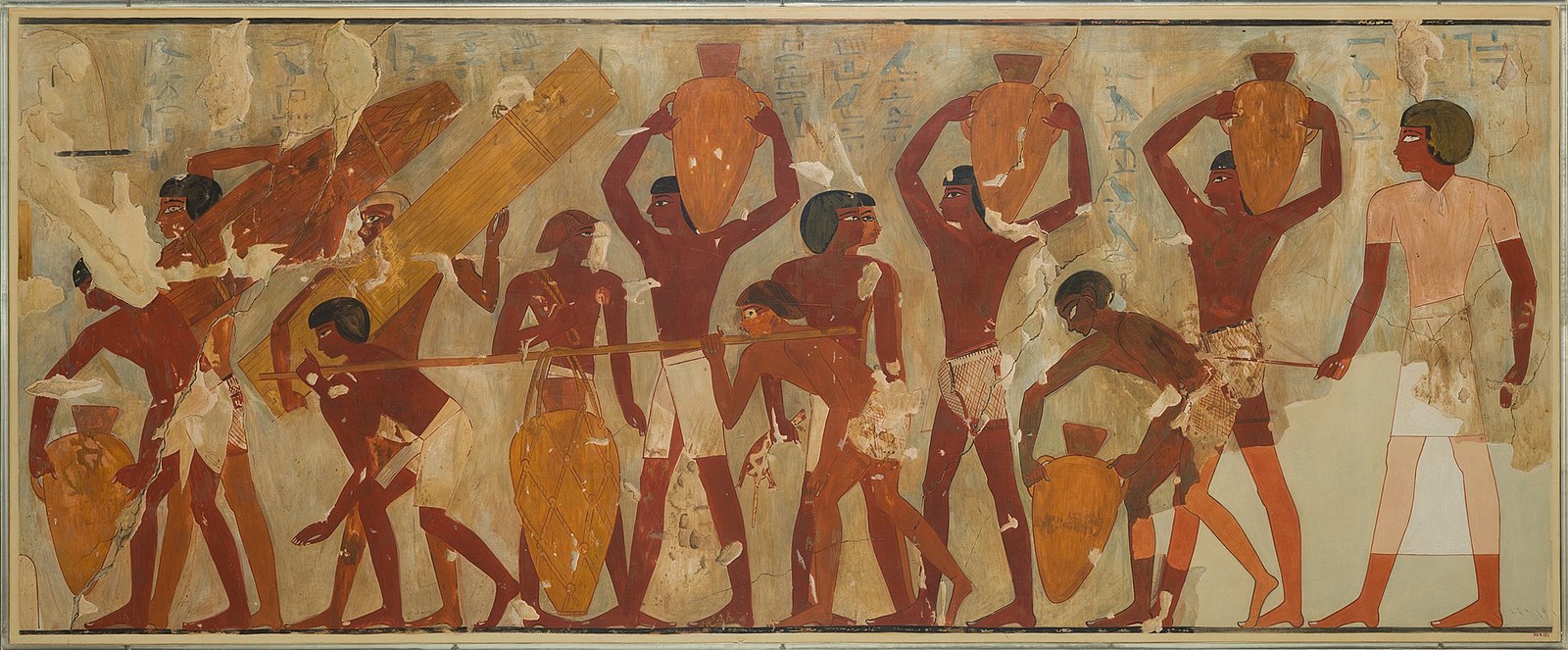

As viticulture is more labor-intensive and lower in yield than the production of barley for beer and wheat for ale, grape wine soon came to be associated with wealthy private landowners, relatively well-paid specialists, and tax-collecting rulers and administrators of all sorts. This was seen most prominently in the Isthmus of Agratekt, where rigidly hierarchical city-states and monarchies once commanded massive irrigation projects. Agratekti nobles and priests found wine to be useful as a social lubricant and as an effective alternative to currency for paying their subordinates, ensuring the drink’s prominence in high society. By the first golden age of Agratekti civilization (roughly 1400 to 1800 HE), Agratekti urban centers were host to the largest varieties of wines, whether home-produced or imported, and the prestige of Agratekti high society and its vints eclipsed that of even the most powerful Saukkanese chiefdoms, never mind those of the Haifatneh Basin and elsewhere in the Northwest.Adulteration or purity?

Viniculture elsewhere in the ancient Northwest

The Agratekti vocabulary of wines (and their at times pretentious approach to drinking) made its way across the trade routes to many polities throughout the Basin, thus partially consolidating a unified wine culture across much of the Northwest. Nearly all the Agratekti terminology for wine flavors and characteristics has been fully retained, save for superficial changes in pronunciation, in the Haifatnehti dialects. A few exceptions elsewhere in the Northwest are worth noting, however. Viticulture does not appear to have taken hold among any of the civilizations across the subcontinent of Takhet. This might be a predictable outcome in Far Takhet, a desert expanse populated by a smattering of camel-herding nomads, though it is possible that some of the ruins there hold historical evidence waiting to be uncovered. The soaring mountains and scorching inland valley of Takhet Alay seem inhospitable to both civilization and agriculture. But Coastal Takhet has long hosted sizable maritime communities, and the drier foothills between the coast and the mountains ought to have potential for viticulture. Yet even the proximity of the Isthmus of Agratekt did not noticeably influence the drinking cultures of Takhet. The wet season and hurricanes of Near Takhet’s cooler months bring ample moisture to the high mountains, producing abundant snowmelt to feed crops during the dry, sunny half of the year. Certainly, yields of cereal grains and fruits are high, at least when storms and droughts do not damage crops. Local tastes or social mores might account for the lack of viticulture in Near Takhet instead. The herding nomads of Far Takhet have historically dominated the overland trade caravans of the western Haifatneh Basin and Agratekt; being that herders are accustomed to more meat and fat in their diets, Agratekti wines may have simply been distasteful to them and thus overlooked as exports. Yet Takheti traders were surely savvy as to the tastes of potential customers abroad. The communities of Near Takhet have also been stereotyped as being relatively conservative—as seen, most notably, with their apparent acceptance of the Reborn Theocracy’s suzerainty—but if Takheti oral traditions are to be trusted, their notions of morality and uprightness changed dramatically under the Theocracy’s influence. A reserved attitudes toward drinking, then, may not have been a significant factor prior to the Internecine Period. In Saukkan-Ghat, meanwhile, resistance to Agratekti wines is more readily attributed to their sometimes defiant preference for stuff fermented from local varietals. After all, one of their most beloved local wines—so dry that Saukkanese hosts rarely offer it to guests from afar—is potently dry and high in tannins that it has long been nicknamed Abzaresh for its supposed ability to make a young man start growing out his beard. As for Shadrusun drinking culture, little is known to human scholars, as is typical of attempts to understand those reclusive people and their civilization. Only a few human scholars in the Revival Era are known to have willingly spent time in Shadrusun communities, and the Shadrusun have proven taciturn when interviewed on topics far more mundane than their physiologies and customs.Hill Wine and Black Wine: Drinking under the Theocracy

While Agratekti leadership in the wine culture of the Northwest managed to persist through the rise and fall of multiple dynasties, and even through the increasing scarcity of water across the Isthmus, it did not survive the persecution of the Reborn Theocracy. Agratekti civilization was already a shadow of its former self when the Order of the Returning Sun carried out their brutal region-wide purge of the Agratekti culture and people, and little now remains of their greatest works, never mind their vints.Your admonitions, my admonitions

While the Reborn Theocracy is rightly seen as enforcing their particular view of moral uprightness throughout the lands they annexed, present-day audiences may be surprised to learn that the Bairhanii religious leaders never wholly banned the consumption of alcoholic drinks. Indeed, not a single telling of the parables from the Collected Wisdom of the Saints implores listeners to abstain from alcoholic drinks entirely; at most, they sometimes encourage moderation and prudence in the cases of those whose vices have worsened their tendencies to harm to themselves or others. Collective mis-rememberings of the Theocracy as enforcing full abstinence from drink might be the result of Wiradinus the Campaigner’s own sobriety and the popularization of abstinence among both the upper priesthood and the Order of the Returning Sun under his influence.Marginalization and Persistence

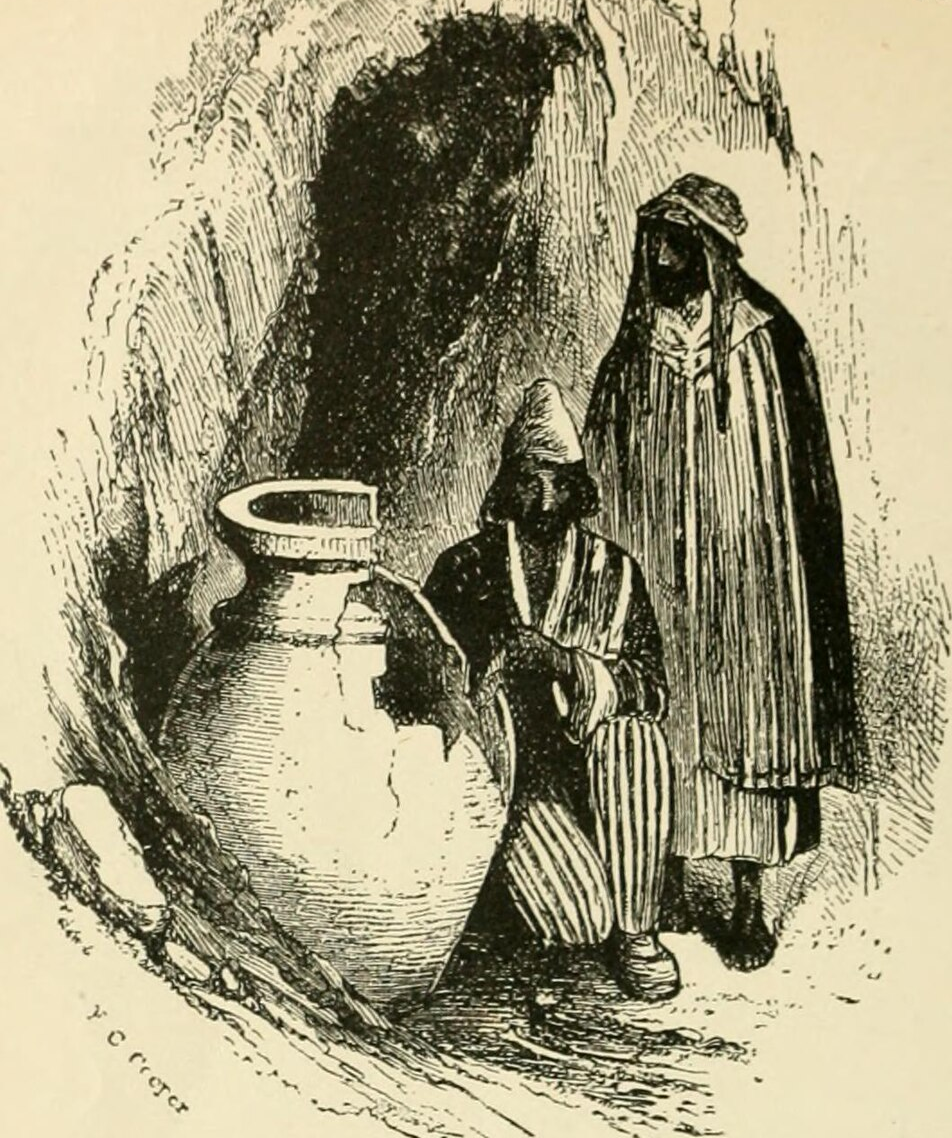

While the particulars of the Theocracy's injunctions against wine consumption may never be definitely established, it remains clear that the authorities took measures to suppress the practice—and it was inevitable that those who lived at the edges of the authorities' reach would find increasingly creative ways to preserve their traditions. Within the Theocracy's core territories—the Gamarh, Laewerge, and Andaen itself—wine production was marginalized to secreted-away places in the few urban centers large enough to host illicit business activities without readily being noticed by city authorities. Vintners in these cities thus had to accept a considerable downgrade in the quality of their vints as they smuggled grapes and hid their fermentation vats away in far-from-ideal conditions. For example, preferable as it may be to crush grapes shortly after harvesting and then promptly move on with preparations for fermentation, in the core territories, grapes from the countryside were often shipped en masse in large crates (under the pretense of being sold for mass consumption the resulting goods were already tarnished and often beginning to turn moldy upon arrival. It is also in these settings that the now-important distinction between red and white wine seems to have developed. Red and other dark wine colors result from grape pulp being fermented with exposure to grape skins and seeds; a whole range of wine colors are possible based on the exact ratios of ingredients. But in Old Agratekt and locales under its influence, the skins were often discarded or used only minimally, as they were seen as resulting in a less "pure" flavor and lighter shades like white and yellow were preferred for their smoothness. In Theocracy-controlled cities, however, grape skins could not conveniently be disposed of as they were obvious evidence of illicit activity; instead, the most convenient way to hide excess grape skins was inside the fermentation vessels themselves. It wasn't long before ethnic Haifah drinkers in these urban areas grew accustomed to their mouth-puckering reds, regardless of their predecessors' tastes. (It remains a matter of etymological dispute whether the epithet "black wine" refers to the pitch-black cellars and other hiding places where urbanists' fermentation vessels were stashed or to the color of the wine itself as characterized by naysayers.) It was in the Theocracy's frontiers and beyond its borders, if anything, where a diverse and robust viticulture thrived. The far south of the Haifatneh Basin, from the coast to the rugged hills of the Sheven Bounds, was a rare locale which was both (largely) beyond the Theocracy's imperial reach and graced with adequate access to fresh water for agricultural productivity. (The aforementioned southeast saw a few wine-growing operations but it relatively arid, even during the Haifatnehti winter.) Those southern Haifatnehti vinyards nestled in the hills additionally enjoyed a cooler (though not exceedingly harsh) winter as well as a fairly hot summer; the grapevines turned out to thrive from the combination of the two, yielding consistent harvests of sweet, juicy wineberries. Vintners in this region were also freer to use the most suitable earthenware vessels for fermentation, unlike their northern, urban counterparts who, if anything, resorted to using the least probably vessels for wine, including metal ones, as these were the least likely to be searched during stings targeting underground businesses. Haifah viticulture remains largely Southern in its varietals, yeasts, and the types of storage vessels that are considered ideal to this day.Revival Era; Revival Wines

The years-long rebuilding of Andaen and the century or so of civilizational instability that followed the Campaign of Reconquest was not conducive to the flourishment of the arts and high culture, less so cuisine. In fact, the Grim Era is broadly viewed as a time when drinking was more often a self-medicating activity than a social one (though this is an oversimplification, as is any attempt to characterized six-odd centuries of history in a single statement). Advances in viniculture and viticulture slowly trickled from the southern Haifatneh region and the distant reaches of Saukkan-Ghat where they were most robust, but progress in these areas accelerated greatly in the end years of the Grim Era and the onset of the Revival Era. Aside from the steadily faster propagation of Southern-style styles (and of Saukkanese styles around the Bay of Maherat), many other Revival Era developments in the Northwest's viniculture have resulted from the spirit of inquiry, experimentation, and consumerism that era has ushered in. A great many brews, incorporating wine grapes or not, were either traditional or novel liquid remedies for one ailment or another, meeting increasingly relevant needs across the urbanizing (and therefore overcrowded, diseased, and polluted) population centers of the Haifatneh coasts. A demand for overall higher-quality wine, likewise, is fueled by the growing wealthy class of merchants and entrepreneurs in Andaen and other prominent Haifatneh city-states. The tastes of this class (and for wine-selling entrepreneurs, their clienete) grow ever more diverse, too, as the (hegemonic) regional peace under Andaen helps interregional trade to thrive.Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Great Job! :D

Thank you! (Somehow I hadn't seen this until now!)

its ok XD Great Article still!