Litchmoor University

Litchmoor University (/ˈlɪtʃ mʊ(ə)ɹ/) is a private non-sectarian research university located in Madbury, New Hampshire. Founded in 1731 as the College at Dover, it was later renamed Litchmoor College to honor early benefactor Ichabod Litchmoor, who bequeathed his farm and extensive library to the school in 1732. The first Bachelor of Arts degrees were awarded in 1735. The school granted its first law degrees in 1855, its first PhD in 1877, and reorganized as a university in 1891. Litchmoor University is one of the original 15 members of the Association of American Universities, the country's most prestigious alliance of research universities.

One of ten colonial colleges founded prior to the Declaration of Independence, it is the oldest institution of higher learning in New Hampshire and the fourth oldest in the United States, preceded by only Harvard, William & Mary, and Yale. Although older than most Ivy League schools, Litchmoor has fastidiously eschewed that particular description, preferring to be identified as the “Venerable Institute,” and tracing its academic heritage, through the Litchmoor Collection, to twelfth century Staffordshire in England.

The school was established by an act of the New Hampshire colonial legislature in response to a petition dated August 12, 1730, signed by three ministers and four laymen, all of “Dover Vicinitie” and claiming to be “dreadful of the prospect of a benighted ministry in the Province, when its current clergymen shall lie moldering in their graves.”

In its early years, the school taught theology, philosophy and the classical languages as the underpinnings of a curriculum designed to train young men for the ministry. The original curriculum became increasingly secularized in the mid-18th century, and the faculty was presenting courses in the humanities, mathematics and the sciences by the time of the American Revolution. In the 19th century, Litchmoor further expanded its course offerings by adding graduate and professional instruction, awarding its first post-baccalaureate degrees in 1855.

Litchmoor University is currently comprised of five academic faculties serving seven constituent colleges. The Faculty of Arts & Sciences is the oldest and largest, divided into 21 departments. It oversees the university’s two undergraduate colleges, Litchmoor College (the original undergraduate college for men) and Eidolon College (undergraduate college for women founded in 1875), as well as the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences (founded 1869). Postgraduate faculties include the Faculty of Law (Litchmoor College of Law, founded 1853), the Faculty of Divinity (Litchmoor Divinity School, founded 1866), the Faculty of Medicine & Public Health (Litchmoor-Elliot Medical School, founded 1888), and the Faculty of Business (Chas. Coffin Graduate School of Business, founded 1907).

The university is overseen by an independent, self-perpetuating Board of Incorporators, who appoint the President, Provost and senior administration. Within the university structure, each faculty defines its own admission standards, curriculum and degree programs with relative autonomy. Litchmoor's endowment is valued at $394 million. Its main campus occupies 600 acres in Madbury, while the 66-acre Medical School campus is located in Manchester. With a total student enrollment of 5,783, Litchmoor is smaller than all of the Ivy League universities.

The faculty and alumni of Litchmoor University have long been recognized for their scholarship, research leadership and many other accomplishments. They have numbered among their ranks numerous MacArthur Fellows, Guggenheim Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Fulbright Scholars. The current faculty includes several members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Included among Litchmoor’s notable alumni are a number of United States Senators and Congressmen, foreign heads of state, governors, federal and state judges, ambassadors, and cabinet members in three presidential administrations. Other alumni have gone on to become Pulitzer Prize winners, Grammy Award winners, Medal of Honor recipients, Olympic medalists, a Nobel Lauriat and a NASA astronaut.

James White acted as clerk of the company and is believed to be responsible for including in the petition the colorfully morbid language regarding decomposing ministers. The petitioners were (in the order they signed) Rev. Samuel Wilson, Rev. Thomas Look, Rev. Jonathan Cushing, Capt. Armstrong Smith, Ambrose Hale, Esq., the aforementioned James White, Esq., and Ichabod Litchmoor, Esq. They would become the original "Board of Incorporators of the College at Dover and Trustees of the College Trust," established March 13, 1731 by legislative charter. Ambrose Hale was named President of the College, and the school's first lectures were conducted in the parlor of his home on Varney Road. He would remain in the role of president until 1744.

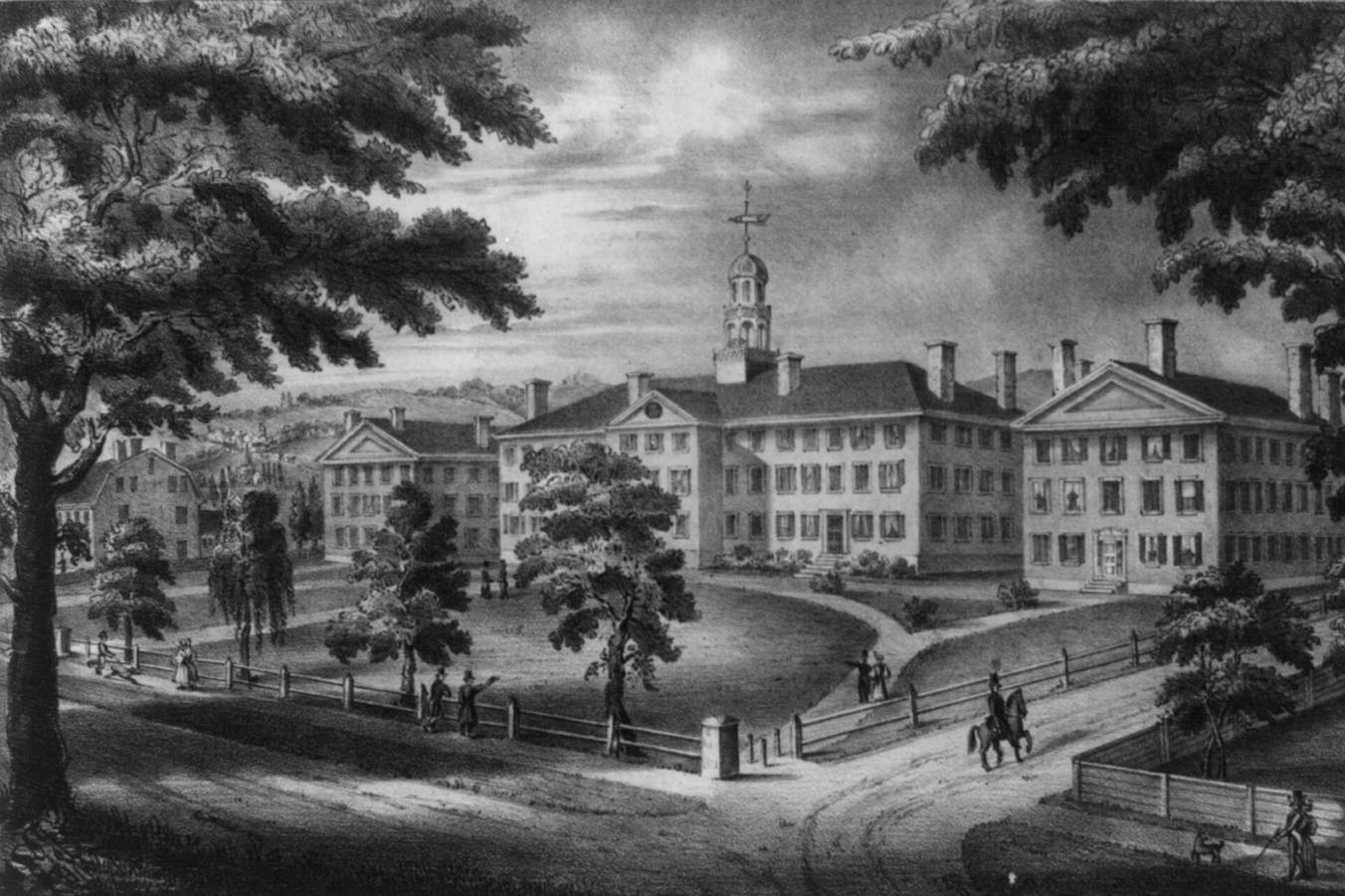

The college's first dormitory houses, constructed between 1733 and 1736, still stand as part of the "Ancient Quad," as does the original President's House, completed in the autumn of 1737. The Litchmoor Memorial Library, home to the priceless Litchmoor Collection, was completed on the site of the original farmhouse, also in 1737. Dover Hall was completed in 1739, followed by Smith Hall, named for Capt. Armstrong Smith, in 1742.

The new college quickly developed a reputation for academic excellence, attracting many talented instructors to its faculty and an ever-increasing number of promising scholars to its student body. As the school grew both in size and in prestige, the faculty expanded the course offerings of philosophy, theology, Latin and Greek, by adding the humanities, mathematics and the sciences to the curriculum.

As political tensions slowly mounted between the colonists and the local English authorities, especially after the occupation of Boston in October of 1768, the college became increasingly aligned with the colonial cause. In the fall of 1776, with British ships patrolling off the coast and threatening Portsmouth Harbor, the entire contents of the school's library were removed for safekeeping to a secret location, mysteriously described in but a single reference as "the vault," and returned only after the end of hostilities.

One of ten colonial colleges founded prior to the Declaration of Independence, it is the oldest institution of higher learning in New Hampshire and the fourth oldest in the United States, preceded by only Harvard, William & Mary, and Yale. Although older than most Ivy League schools, Litchmoor has fastidiously eschewed that particular description, preferring to be identified as the “Venerable Institute,” and tracing its academic heritage, through the Litchmoor Collection, to twelfth century Staffordshire in England.

The school was established by an act of the New Hampshire colonial legislature in response to a petition dated August 12, 1730, signed by three ministers and four laymen, all of “Dover Vicinitie” and claiming to be “dreadful of the prospect of a benighted ministry in the Province, when its current clergymen shall lie moldering in their graves.”

In its early years, the school taught theology, philosophy and the classical languages as the underpinnings of a curriculum designed to train young men for the ministry. The original curriculum became increasingly secularized in the mid-18th century, and the faculty was presenting courses in the humanities, mathematics and the sciences by the time of the American Revolution. In the 19th century, Litchmoor further expanded its course offerings by adding graduate and professional instruction, awarding its first post-baccalaureate degrees in 1855.

Litchmoor University is currently comprised of five academic faculties serving seven constituent colleges. The Faculty of Arts & Sciences is the oldest and largest, divided into 21 departments. It oversees the university’s two undergraduate colleges, Litchmoor College (the original undergraduate college for men) and Eidolon College (undergraduate college for women founded in 1875), as well as the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences (founded 1869). Postgraduate faculties include the Faculty of Law (Litchmoor College of Law, founded 1853), the Faculty of Divinity (Litchmoor Divinity School, founded 1866), the Faculty of Medicine & Public Health (Litchmoor-Elliot Medical School, founded 1888), and the Faculty of Business (Chas. Coffin Graduate School of Business, founded 1907).

The university is overseen by an independent, self-perpetuating Board of Incorporators, who appoint the President, Provost and senior administration. Within the university structure, each faculty defines its own admission standards, curriculum and degree programs with relative autonomy. Litchmoor's endowment is valued at $394 million. Its main campus occupies 600 acres in Madbury, while the 66-acre Medical School campus is located in Manchester. With a total student enrollment of 5,783, Litchmoor is smaller than all of the Ivy League universities.

The faculty and alumni of Litchmoor University have long been recognized for their scholarship, research leadership and many other accomplishments. They have numbered among their ranks numerous MacArthur Fellows, Guggenheim Fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Fulbright Scholars. The current faculty includes several members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Included among Litchmoor’s notable alumni are a number of United States Senators and Congressmen, foreign heads of state, governors, federal and state judges, ambassadors, and cabinet members in three presidential administrations. Other alumni have gone on to become Pulitzer Prize winners, Grammy Award winners, Medal of Honor recipients, Olympic medalists, a Nobel Lauriat and a NASA astronaut.

History

Colonial Era

On Saturday, August 12, 1730, seven gentlemen of Dover, including three clergymen, met at Dame Tibbetts' tavern on Silver Street to discuss the need for an academy to educate the young men of New Hampshire. By the end of the evening, they were bound by common purpose to establish such an institute in the town of Dover, setting their signatures upon a petition to the colonial legislature.James White acted as clerk of the company and is believed to be responsible for including in the petition the colorfully morbid language regarding decomposing ministers. The petitioners were (in the order they signed) Rev. Samuel Wilson, Rev. Thomas Look, Rev. Jonathan Cushing, Capt. Armstrong Smith, Ambrose Hale, Esq., the aforementioned James White, Esq., and Ichabod Litchmoor, Esq. They would become the original "Board of Incorporators of the College at Dover and Trustees of the College Trust," established March 13, 1731 by legislative charter. Ambrose Hale was named President of the College, and the school's first lectures were conducted in the parlor of his home on Varney Road. He would remain in the role of president until 1744.

The effort to locate a permanent site for the new school was resolved in late 1732 when, upon his death at the age of 78, Ichabod Litchmoor bequeathed his 600-acre farm and extensive personal library of over 5600 volumes to the Dover College Trust. Upon moving to its new location overlooking the Winniconic valley, the school was renamed Litchmoor College and began a period of rapid expansion. The Board of Incorporators established a building committee to design a plan for the school's future campus and in 1735 Litchmoor Hall, the college's focal point and main classroom building, was completed at the top of newly renamed College Hill.

The college's first dormitory houses, constructed between 1733 and 1736, still stand as part of the "Ancient Quad," as does the original President's House, completed in the autumn of 1737. The Litchmoor Memorial Library, home to the priceless Litchmoor Collection, was completed on the site of the original farmhouse, also in 1737. Dover Hall was completed in 1739, followed by Smith Hall, named for Capt. Armstrong Smith, in 1742.

The new college quickly developed a reputation for academic excellence, attracting many talented instructors to its faculty and an ever-increasing number of promising scholars to its student body. As the school grew both in size and in prestige, the faculty expanded the course offerings of philosophy, theology, Latin and Greek, by adding the humanities, mathematics and the sciences to the curriculum.

As political tensions slowly mounted between the colonists and the local English authorities, especially after the occupation of Boston in October of 1768, the college became increasingly aligned with the colonial cause. In the fall of 1776, with British ships patrolling off the coast and threatening Portsmouth Harbor, the entire contents of the school's library were removed for safekeeping to a secret location, mysteriously described in but a single reference as "the vault," and returned only after the end of hostilities.

Nineteenth Century

On the bitter-cold night of Sunday, January 3, 1819, a hot ember escaped from the improperly closed gate of a heating stove on the first floor of Litchmoor Hall, igniting a fire. Soon flames raged through the entire building and could be seen for miles around. At 9:30 the cupola was ablaze, and by 10:00 the entire roof had completely fallen in. By dawn nothing stood among the smoldering ashes but the outer walls. It would take two years to rebuild Litchmoor Hall, which was rededicated in June of 1821, its scorched bricks painted white. Dover Hall and Smith Hall were painted white in 1825, and the three main classroom buildings facing College Lawn have remained that way ever since, inspiring the title of the schools alma mater: "The White Halls of Litchmoor."In 1853, John P. Hale, the former U.S. Senator from New Hampshire, and great-great-grandson of Litchmoor's first president, joined the faculty and began offering lectures and seminars in the law to Litchmoor graduates. In 1855, four Litchmoor graduates were awarded their Bachelor of Laws degree after successfully completing Senator Hale's course of study. They were the first post-baccalaureate degrees issued by the college, and it was from those humble yet auspicious beginnings that the renowned Litchmoor College of Law was born.

During the following decade, as the clouds of civil war gathered on the nation's horizon, the college would face many challenges. Not the least of these was a sudden decline in enrollment during the winter recess of 1860-61, when virtually all of Litchmoor's southern students left the school to join the Confederate cause, never to return again. Despite the difficult trials of the war though, the late-nineteenth century ushered in another period of expansion for Litchmoor College.

Shortly after the conclusion of the War of the Rebellion, the Board of Incorporators petitioned the New Hampshire General Court for authority to issue postgraduate degrees and were granted that authority in June 1866. In 1869, the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences was formed, and Litchmoor awarded its first Master of Arts and Master of Science degrees in 1872. During the post-Civil War period, Litchmoor witnessed a marked increase in student body enrollment.

In 1865, Mrs. Ruth Hellesby Coffin, wife of millionaire Charles O. Coffin, suggested in a letter to the Board of Incorporators that Litchmoor's curriculum ought to be further expanded to include the broader and deeper study of religion and theology, and offered financial support to promote such an augmentation. This suggestion, accompanied by her very substantial endowment of $100,000, led the following year to the establishment of the Litchmoor Divinity School. An important stipulation contained in the original trust documents requires that a chair on the faculty be perpetually reserved for a Roman Catholic theologian.

That same year, 1865, several members of the Litchmoor faculty were persuaded by Mrs. Coffin to conduct a series of lectures for a group of local society ladies and their daughters at the Coffinhurst Estate, in exchange for a rather generous honorarium. The lectures were extremely popular and well-attended, and the Litchmoor Collegiate Lecture Series for Women became an annual occurrence during the summer recess. After extensive negotiation with the Board of Incorporators, and the offer of another substantial endowment from the Coffin fortune, the Eidolon College for Women was established in 1875 (the name was suggested by Mrs. Coffin as representing the idealization of the female spirit).

In 1880, a bequest by the widow of Dr. John Seaver Elliot led to the purchase of 66 acres in east Manchester, which would become the site of the future Elliot Hospital. As the 25-bed facility neared completion in Manchester, the trustees of the new hospital joined with Litchmoor's Board of Incorporators to form the Litchmoor-Elliot Medical School, established in 1888. It has since become one of New England's preeminent teaching hospitals.

Twentieth Century

The turn of the century brought more growth and innovation to Litchmoor University. Under President Winslow F. Morton (1901–1921), the school undertook a major revitalization effort, modernizing its facilities, expanding its faculty and increasing its endowment, which resulted in the near doubling of total enrollment by the end of his tenure.Thirteen new buildings were constructed between 1903 and 1921, to replace antiquated classroom and dormitory facilities. A third major contribution from the Coffin family in 1905 led to the establishment of the Charles O. Coffin Graduate School of Business two years later in 1907. This time period is often referred to as the "rebirth of Litchmoor."

When the United States became involved in World War I, Morton offered all of Litchmoor's available resources to the war effort. Several military training schools opened on the campus, and laboratories and other facilities were dedicated to military research. More than 2,500 Litchmoor students served in the armed forces, with over 100 dying in the war. After the armistice, Litchmoor saw another spike in enrollment.

As a result, in 1920 the university instituted a selective admissions policy which took into account the applicant's "character, initiative, and broadness of interests, along with a record of demonstrated scholastic aptitude." Some have argued the unstated purpose of the policy was to maintain among the student body a "healthy proportion" of white protestants from elite families. Debate over the policy has continued to the present day, and while it remains the official policy of the university, it has been modified several times over the years, resulting in an ever more vibrant and diverse student body.

The interwar years presented the university with a number of unanticipated challenges. The Great Depression made it impossible for many students to remain in school, and enrollment of new students declined precipitously. In response, University President Zachary G. Underhill (1929-1936) established the Litchmoor School of Continuing Education, which offered college level courses to both men and women for a fee, without the requirement of an entrance exam or full enrollment in a four-year undergraduate program.

The novel and innovative school drew its instructors from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and utilized existing classroom facilities. After 1935, many classes were scheduled during the evening to make them more accessible to students who worked during the daytime. The courses became extremely popular, especially among working adults and professionals in the surrounding area, while providing much needed revenue during difficult economic times. The school was disbanded in 1947.

From 1942 until 1945, to support the American effort in World War II, Litchmoor participated with 130 other colleges and universities in the V-12 Navy College Training Program, designed to produce large numbers of U.S. Navy and Marine Corps officers. As happened in the previous war, many Litchmoor University students interrupted their studies to serve their country. Of the 7,549 Litchmoor men and women who served in the armed forces during World War II, over 250 were killed in action.

After the war, Litchmoor University entered yet another period of expansion and transition. The federal GI Bill made it possible for large numbers of middle-class students from a wide variety of backgrounds to seek the college education that may have been foreclosed to them in the past. This caused enrollment applications to soar, and a corresponding steady increase in the student population. Veterans were admitted under a program that credited their wartime service and utilized special entrance exams. Applications from foreign students also rose dramatically.

As a result, diversity among the student body grew steadily in the post-war years. This was mirrored by deliberate hiring policy changes instituted by University President Gordon K. Fairclough (1936–1951), which encouraged the addition of more women and minorities to the ranks of instructors, resulting in an ever more diverse faculty as well. Fairclough's policies were augmented by a renewal of the university's strong emphasis on a traditional liberal arts education, a rededication to the principles of diversity and inclusiveness, and an expansion of the school's academic focus to include public policy and international relations.

Perhaps because of its progressive, well-defined free speech and debate policies, Litchmoor has been fortunate in its ability to avoid the violence and unrest that has plagued many colleges and universities in recent years. The university Code of Conduct encourages free and open dialogue among its students and faculty on all topics of current interest, demands honesty and candor in the course of that dialogue, and insists upon respect for all points of view. The school regularly opens its facilities to peaceful public debate on virtually all issues.

This Article to be continued...

Litchmoor University

PRIVATE UNIVERSITY

Latin: Universitas Lyccidmoriensis

Motto

Memento Praeteritum

("Remember the Past”)

("Remember the Past”)

Alma Mater

The White Halls of Litchmoor

Former names

Dover College

(1731–1733)

Litchmoor College

(1733–1891)

Type

Private research

university

Established

March 13, 1731

Founders

Samuel Wilson

Thomas Look

Jonathan Cushing

Armstrong Smith

Ambrose Hale

James White

Ichab. Litchmoor

Accreditation

NECHE

Affiliation

AAU

Endowment

$394 million (1960)

Annual Tuition

$8,635 (1960-61)

President

L. Hayward Dodge

Provost

Braxton G. Tuff

Academic staff

894

Students

5,783

• Undergraduates

3,155

• Postgraduates

2,628

Location

Madbury,

New Hampshire

United States

Main Campus

College town

600 acres

Medical Campus

Urban

66 acres

Newspaper

The Black Letter

Yearbook

The Annual

Pitch black

Nickname

The Gravediggers

Mascot

Grimm the Reaper

Litchmoor University

525 Litchmoor Road

Madbury, New Hampshire

Telephone: PAvilion 2-4200

(central switchboard)

525 Litchmoor Road

Madbury, New Hampshire

Telephone: PAvilion 2-4200

(central switchboard)

Comments