Merfolk

Those who call the water home

A silent shimmer of scales and a flicker of fins

disappearing into the dark depths below

and leaving me alone.

Merfolk are the most evolutionarily diverse of the four sapient species of Etrea, having diverged from the shared genetic ancestor long before the other three. Scientists have identified three distinct subspecies of merfolk, as well as many variants and phenotypes within these subspecies. All merfolk live their lives primarily in and under the water, though they must all return to the surface to breathe air. Societies of merfolk exist in every ocean in Etrea, as well as many of its freshwater systems.

Characteristics

Anatomy

Due to the diversity of merfolk species, it is difficult to give an overview of a typical merfolk, though there are several characteristics that all merfolk share. Merfolk are a mixture of humanoid and ichthyoid features, though the ratio of this changes from species to species. Some merfolk are almost entirely humanoid, whilst others fall much more on the fishlike side of the spectrum.Like other sapient species, all merfolk have large complex brains with a well-developed pre-frontal cortex. This allows for greater cognitive function, such as the ability for introspection, imagination, and self-awareness. At the base of their skulls, under their brains, they have an organ known as the altus, which allows for the conversion of energy and magic.

Generally, the top half of a merfolk's body is humanoid, from their head to their waist. Attached to the torso at the shoulders are two arms that end in hands with five fingers, including an opposable thumb. Many merfolk species have a thin membrane between each of their fingers to allow better propulsion through the water.

On the lower half of their bodies, merfolk have a large, muscular tail that ends in a large double fin. This tail is covered in overlapping scales formed of keratin.

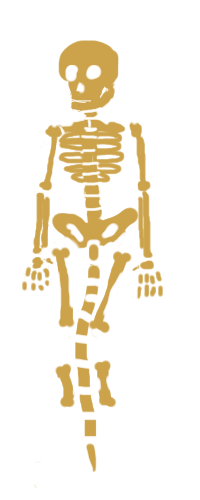

Skeletally, merfolk tails are made up of an elongated spine, continuing all the way down to the fins. A pelvic bone is often present where it would be on a human, though often it is an open structure rather than a closed one. The pelvis offers some protection to the lower organs, but it is not mechanically important in the way that it is in other sapient species. The majority of merfolk also have vestigial bones in their tails where legs once existed, though these are usually floating and not attached to the main skeleton. Many scholars believe that the extra bones serve no structural purpose.

Of the four sapient species, merfolk have the most variety in facial features and structures. Most merfolk have a second pair of eyelids underneath their primary pair. These can be translucent or transparent, and remain closed whilst the face is submerged. This protects the eyes from both water and debris. Another feature that is common to around half of merfolk species is the lack of a visible nose formed of cartilage. Some have small slits where a nose would be present in other species, or nothing at all. Other merfolk have barbels growing from their lips or just above their mouths, which perform a similar function.

Merfolk teeth can come in different shapes and sizes, depending on what that particular group of merfolk have adapted to eat. Some have flat teeth for grinding plant matter, whilst others have pointed or needle-like teeth. In some cases, their teeth protrude from the mouth like fangs.

In general, merfolk have larger lungs than other sapient species, as they are able to hold their breaths for hours at a time. Whilst they have to surface to breathe oxygen, some merfolk only have to do so a few times a day. It is theorised by scientists that there is a magical component to their ability to hold their breaths so long, but nothing has yet been proven.

Merfolk have a cloaca at the front of their tail, just below the waistline. This is used to excrete waste products, as well as for reproduction. To reproduce, the male and female merfolk wrap their tails around each other and the male passes sperm from his cloaca to the female's.

Subspecies

As well as so-called 'generic' merfolk, three different subspecies have been identified by scientists. These subspecies have attributes that set them apart in some way, leading them to be categorised separately.Freshwater Merfolk

Freshwater merfolk are a subspecies that generally encompasses those merfolk who spend their lives in freshwater, though there are several freshwater variants who do not fit under this umbrella. Several merfolk variants that seasonally migrate between salt- and freshwater can also be categorised under this subspecies.Freshwater merfolk tend to be rather drab in regards to their scale colour, tending towards browns, greys, and silvers. This allows them better camouflage in shallower waters, blending them with the sunlight flashing against the surface of the water, or the rocky, sandy bottom of the river or lake. This aids them in hunting for live food, as well as avoiding the larger predators some share their waters with.

Seventy-five percent of freshwater merfolk have barbels in place of a nose, with some growing long enough to reach the chest. These barbels are used for both navigation and hunting; they can sense small changes in electromagnetic fields, allowing the merfolk to hunt effectively in murky water where they cannot rely on their eyes.

In general, freshwater merfolk are unable to hold their breaths for as long as other merfolk. Some scholars theorised that it is due to many living in shallower waters, whilst others believe the salt in the ocean amplifies whatever innate magic merfolk use to lengthen their submersion.

Polar Merfolk

Polar merfolk are the least diverse subspecies of merfolk, with only fourdistinct variants. One of these groups lives in the Frozen North of Etrea, inhabiting the expansive merfolk city of Qasceile. Two other groups live in the far south, in the cold waters around the Barren. The final group of polar merfolk are nomadic, travelling annually between the northern and southern poles of the planet.All polar merfolk are huge in size, with the largest variant weighing several tons and measuring up to forty-eight feet in length. Their size comes with increased lung capacity compared to other merfolk; some polar merfolk can go up to twenty-four hours without having to surface for oxygen.

Most polar merfolk have a large ratio of body fat to muscle, providing them with better insulation for the freezing waters they live in. To sustain themselves, they need to eat copious amounts of food, often having meals up to five times per day. The nomadic variant of polar merfolk are much sleeker, with powerful muscles that allow them to travel vast distances in a single day.

Deep Ocean Merfolk

The name 'deep ocean merfolk' is something of a misnomer, as all merfolk are unable to withstand the pressure of the darkest depths of the world's seas. However, they do live in much deeper water than other merfolk, with some living in places where sunlight barely reaches. Due to the scarcity of light, deep ocean merfolk often have larger eyes to improve their vision in the dark, or rely more heavily on their other senses.Unlike other merfolk, deep ocean merfolk have evolved gill-like structures that allow them to filter oxygen from the water around them. This means that they rarely surface, and most go their whole lives without doing so. They are capable of breathing air, as they still have rudimentary lungs, but most find this uncomfortable.

There is some debate amongst scholars as to whether deep ocean merfolk can truly be counted as sapient beings, as not much contact has been made, and much of what has occurred has been hostile. The general consensus in academic circles is that this view is incorrect and borne from prejudice.

Biological Variation

Merfolk can possess a large range of different skin tones, from an almost translucent light colour to a deep rich brown. Skin colour generally corresponds to geographic location, with lighter-skinned merfolk living in colder or deeper water than darker-skinned merfolk. Scale colours are even more varied. Some merfolk have more neutral-coloured scales in browns, golds, and silvers, and others have much brighter colours like reds, blues, greens, and pinks. Whilst many merfolk have scales of only one colour or a gradient of two to three, some merfolk possess vibrant or complicated patterns. In freshwater merfolk, these patterns are often for camouflage, but in others they seem to be more a form of aposematism.Although some groups of merfolk have evolved to have no hair at all, most merfolk have constantly growing hair on their heads. Most male merfolk can also grow facial hair. Like humans, the hair of merfolk can vary in texture, thickness, and colour. Textures can differ between wispy and wiry, and between curly and straight. Hair colours can range from pale blond to black, with a spectrum of dull reds, browns, and golden blonds in between.

Merfolk have the widest variety of eye colours of the four sapient species in Etrea. Like humans, many have eye colours that fall on the spectrums of brown, green, blue, and grey. However, some merfolk have eye colours more unique to the species, including purple, pink, or silver. The congenital condition of heterochromia - that is, eyes of different colours - has a much higher incidence in merfolk than in any other sapient species.

Genetic Compatibility

It is generally accepted that all four sapient species in Etrea evolved from a singular ancestor, known to scholars as the allkin. This theory has been strengthened over the years by the discovery of bone fragments and artefacts, as well as a single frozen and mummified corpse referred to by researchers as 'Mother'. Though the other three species are able to crossbreed, some to a lesser extent than others, merfolk are not genetically compatible with any of them. Mutually pleasurable sexual relationships, however, have been recorded across myth, legend, and history.Merfolk actually have variable reproductive compatibility with others of their own species, the different subspecies having diverged too greatly. The large polar merfolk, for example, cannot reproduce with with any other merfolk due to their size. With other subspecies, however, there are no established rules as to which relationships will provide viable offspring. Some deep ocean merfolk, for example, can reproduce with some variants of freshwater merfolk, but not with others. Merfolk who want the certainty of children, therefore, do not form relationships outside of their group.

Sensory Capabilities

The senses of sight and hearing vary across the species, depending greatly on how each group of merfolk has adapted to their environment. Deep ocean merfolk, for example, generally have a very poor sense of sight, whilst generic merfolk have a sense of sight comparable to that of humans. Many merfolk groups that have a poor sense of sight tend to have a greater sense of hearing. Some groups of deep ocean merfolk, for example, make use of echolocation to navigate their lightless domains.

The majority of merfolk have a weak sense of smell, with many having no sense of smell at all. This does not appear to hinder their sense of taste, however, with merfolk able to pick up on many subtle changes of flavour other species might not. Scholars are as yet unsure of the evolutionary benefit of a merfolk's enhanced sense of taste, although some speculate it has a role in alerting them to food which may be unsafe to consume, or water that is unsafe to traverse.

It is unwise to grab a merman by the tail.

In merfolk, the sense of balance keeps them from getting disorientated when traversing the three-dimensional underwater space. They are always able to tell which way the surface is, which is especially important in dark or murky waters. This innate sense of which way up they are is also extremely useful when they are exploring underwater caves.

Electroreception is a sense that has evolved to be present in the majority of merfolk groups. They are able to sense electrical fields around them with the use of specialised cells located on both their skin and scales. These fields are used for navigation in waters with low visibility, and also for the detection of other lifeforms around them. Some merfolk make use of this sense more than others, with some groups of freshwater merfolk having evolved barbels for more precise electrolocation.

Magical Abilities

Generally, merfolk are considered to not be an especially magical species. Whilst some subspecies have a higher prevalence of magic than others, conservative estimates generally place possession of arcane ability at between ten to fifteen percent of all merfolk. Some scholars think that this number could be as high as thirty percent, particularly as there are still believed to be many uncontacted groups. Merfolk magic, perhaps not surprisingly, is generally focused around water and the ocean, though many groups have other specific niches.There is a subset of academics that argue that magic is actually possessed by all merfolk. It is believed that the altus of merfolk passively convert energy into oxygen, allowing them to last much longer on one breath of air than they otherwise would do. Academic consensus, though, is that magic is a deliberate phenomenon, so, for most, this passive conversion does not count for the purposes of statistics.

In actuality, however, merfolk, like all sapient species, would all be able to use magic if they were to open their minds to it. Magic, after all, is merely the manipulation of energy by the altus. The late Kaienese scholar, Magnus Woolery, hypothesised that all members of all sapient species would be able to use magic if they were correctly trained. He believed the incidence of magic often cited by scholars is actually the percentage of those who have innate talent.

Life Stages

Before Birth

The gestation period for merfolk last between nine and twelve months, depending on the subspecies. Polar merfolk have the longest pregnancies, whilst deep ocean merfolk have the shortest. Generic and freshwater merfolk have a similar pregnancy length as the other three sapient species, lasting for around ten months.Merfolk generally have one baby at a time. Pregnancies with multiple offspring are extremely rare, and pregnancies where more than one survive are even rarer. There are only two recorded incidences of surviving twins in the past one hundred years.

When merfolk give birth, the baby comes out tail first, similar to other aquatic mammals such as whales and dolphins. This prevents the baby from drowning either during or after birth, before they are able to take their first breath.

Whilst childbirth carries a risk, as it does for all sapient species, merfolk mothers are the least likely to experience major complications or to die as a result. Death in infants, however, occurs at a slightly higher rate than in other species.

Infancy

Communication is comprised of a mixture of touch and sound, with the former being most important. Merfolk infants spend ninety-five percent of their time attached to an adult. They communicate their needs, such as hunger, through a mixture of mouthing and tapping with their hands and fingers. Like the infants of other sapient species, merfolk infants also cry; these high-pitched sounds are only utilised when separated from adults and are used by parents to locate their offspring.

Like all mammals, merfolk infants survive solely on milk at first. They are exclusively breastfed by their mother or another female caregiver. Merfolk milk is much thicker in consistency and has a much higher fat content than the milk of other sapient species; this prevents it from disintegrating immediately in the water. At around seven months of age, weaning begins, with different foods being slowly introduced to an infant's diet as teeth begin to grow.

Childhood

Childhood is the period between infancy and puberty, generally coming to an end around the ages of twelve or thirteen. It is a time of great growth and learning, with merfolk children physically growing longer and soaking up the knowledge and life skills they need to survive in Etrea.In most societies, children have much less responsibility than adults, with their time focused on learning and play. This lower standard of responsibility often means that the parents or caregivers take on the consequences of the child's actions. Children also tend to have less rights, often unable to take part in decisions about their own care or how society is run.

Adolescence

Adolescence begins with the onset of puberty, where an increase in the production of hormones leads to changes in a merfolk's growing body. Body hair begins to sprout on the under the arms, on the groin, and, for males, on the face. Bones grow and shift, and body fat and muscles are redistributed, changing the androgynous body of the child into the sexually dimorphic body of an adult.The adolescent years are often considered to be the most dangerous of a merfolk's life. At this point in life, the part of the brain responsible for reasoning is not fully developed, leading to young humans taking risks without fully thinking through the consequences. At the same time, this age is when a human is expected to be taking on more responsibilities; in some cultures, they are even considered to be full adults.

Adulthood

Adulthood is the longest life stage for merfolk, beginning when one is sexually mature and ending when the body or mind begins to deteriorate with age. The exact moments this stage starts and ends varies from merfolk to merfolk and, more notably, culture to culture. In many societies, sexual maturity is not the only mark of adulthood, and a merfolk must reach a certain age or hit a certain cultural milestone to be fully considered an adult.In general, adult merfolk are the ones to give birth to and raise children, and it is at this stage of life that they are most suited to doing so. Elderly merfolk males are still fertile; though this diminishes with age, there does not seem to be an age at which fertility comes to a complete stop. Adolescent merfolk are also known to procreate, though the younger the mother the greater the risk of complications.

Elderhood

Ecology

Habitat

Merfolk live in many of the waterways and oceans of Etrea. Some have been isolated in lakes by the drying up of ancient rivers, whereas others practice a nomadic lifestyle across the seas, travelling from feeding ground to feeding ground. Some have adapted to life in the swamps, and others live their lives on the edge of raging river rapids. Each have adapted to their environments in a variety of ways. Because of these adaptations, most merfolk do not travel, but instead remain in their communities their entire life.The one thing that all merfolk have in common is that they are ill-suited to life on land. Many merfolk can spend a short amount of time out of the water, though they have to drag themselves around with their arms. For merfolk living in isolated bodies of water, this can be an issue during droughts, where water levels can drop dramatically and they have nowhere else to go. Many of these communities have infrastructure and contingencies in place in case of these rare but devastating events.

Diet

Merfolk are primarily hunter-gatherers, though some communities also make use of various types of agriculture. They are an omnivorous species, their diet consisting of mainly plants, fish, and shellfish. Some communities also eat meat and fungi, depending on the resources around them.Whilst most of their food collecting takes place in the water, some merfolk also forage for food on the land directly next to their watery home, such as the bank of a river. In times of desperation, merfolk will travel up to a mile on land in order to find sufficient food.

The majority of merfolk consume all of their food raw; their stomachs are acidic enough to deal with any diseases or parasites that would normally be killed by cooking. Many merfolk can also eat things that would be poisonous to other sapient species, which has caused some issues at diplomatic meetings in the past. However, not all merfolk eschew cooking completely. Some deep sea merfolk cook some of their meals using geothermal vents, and some other communities sometimes construct floating or waterside bonfires for special occasions or festivals.

Behaviour

Social Structure

Merfolk are a highly social species, generally not going more than a day or so without interactions with others. Most activities are done in groups, such as hunting and food preparation. If long excursions are to be undertaken, most merfolk will do so in groups of two or three.Despite being sociable, merfolk do not tend to mix with other species, or with merfolk outside of their own group. This is more an issue of logistics than xenophobia. With other sapient species, the gap between land and water is quite an obstacle to overcome, though specialised floating outposts have been created in places for trade and diplomacy. Other groups of merfolk are more complicated, as many groups have unique adaptations to live in their habitat, and another merfolk, particularly from a different subspecies, may have difficulty remaining in a different environment for long. This is not always the case, and there are numerous examples throughout history of merfolk adapting well to a new group, and even several stories of a freshwater merfolk adjusting to life in the ocean or vice versa.

Merfolk communities vary in size, with the smallest examples consisting of less than ten people, and the largest, the under-ice city of Qasceile, which boasts a population of around ten thousand polar merfolk. In some merfolk cultures, it is not uncommon for young merfolk to break off from their community to form a new group.

Whilst romantic and sexual norms vary by culture, merfolk are generally both monogamous and heterosexual. However, same sex relationships are relatively common across many cultures; many merfolks have the capacity to be attracted to any and all genders. As well as this, polyamory is practiced in places all across Etrea, and is considered in some countries to be beneficial in rearing children. All cultures have a strong taboo against incestuous relationships, particularly between parent and child.

Communication

Like other sapient species, merfolk communicate through language, both spoken and written. Language is unique to the sapient species of Etrea, particularly in its ability to get across abstracts concepts such as time and imagination. Whilst other species communicate, they do so about concrete things happening in the present.There are many different merfolk languages across Etrea, most made up of a variety of sounds that convey a near infinite amount of ideas. Clicking and whistling are the most common sounds in the languages of merfolk, though a variety of other sounds are utilised. Many merfolk languages are also extremely tactile, relying just as much on touch as on sound. Body language, including tail movement and facial expressions, also play a vital role in communication.

Most merfolk languages do not have a written component. This is theorised to be due to the difficulty of permanency in the underwater world. Many of the methods used by other sapient species, such as parchment and ink, would disintegrate or fail when submerged. Other methods, such as carving messages into stone, are laborious and time-consuming, or could erode over time due the movement of the water. Some groups of merfolk feel that record-keeping is worth the time and effort it takes, and a few cultures have rich, intricate written languages comparable to land-based ones.

A few common written languages have been developed for trade purposes between groups of merfolk. Often these are simple marks slashed into pebbles or a series of hand signs. When it comes to trading with other sapient species, some merfolk do learn the languages used on land, though this is a rather niche skill. Generally, only one or two merfolk in a large settlement will bother with it. For some groups, their adapted anatomy makes speaking these languages difficult.

Mythology

One of the most common myths across Etrea features malicious merfolk who lure sailors in to crash their ships onto sharp rocks and shallow ground. Often, if the sailors survive the shipwreck, they are deliberately drowned and occasionally even eaten. The merfolk in these myths are generally female and devastatingly beautiful. In many versions, they call to the sailors with music or song, and in others the sailors are drawn in with a bewitching power.

In many places across Etrea there are also myths of snake people. These legends are usually located around swamps or other wetland, in places where freshwater merfolk could thrive. It is generally accepted by scholars of folklore that the origin of these myths is from people catching glimpses of merfolk in murky water.

Many cultures also have myths surrounding the origin of merfolk, created long before the theory that all sapient species evolved from a common ancestor. These stories vary from merfolk springing forth from the spilt blood of an ancient sea god, to macabre experiments on sealife, to a romance between a human and a sea monster.

Merfolk themselves have a deep respect for the ocean. Even freshwater merfolk who never lay eyes on the sea itself have ancient stories of a large, unending body of water. Many of the stories in merfolk mythology centre around the many mysteries of the deepest reaches of the oceans, and the life that may be hidden within.

i think the merfolk may be my favourite too! i love the art in this article, it was nice to see what their skeleton is like. as always reading your articles is a joy <3

Thank you so much! I'm really pleased with the art, looking forward to replacing more of it with my own stuff. :)