The Magic of Coal

Table of Contents

Ah, coal! Magical and mystical coal! Think of all the mighty creatures that have died eons ago to give this small lump...

Origin

Everyone knows coal comes from the gigantic sentient and very aggressive trees that preceded us on Earth. Thankfully, humanity has got rid of all of them by now!

When dead plant matter decays, it can be protected from biodegradation and oxidation by mud or acidic water for example. It can them form a peat bog, trapping all the magic and carbon and preventing them from dissolving into the environment. That peat then gets deeply buried under sediment, subjected to high heat and pressure. This provokes the loss of water, methane, and carbon dioxide, and so it increases the proportion of carbon and magic into the matter. Several million years of this treatment turns that matter into coal that is nowadays found in underground layers called coal seams inside the sedimentary rocks.

Artificial coal or charcoal can also be formed by heating wood up to 300°C. However, this coal is much younger and so it has a different composition and contains less magic. It is what has long been used by humanity, and it is only the disappearance of many forests that led us to the search for other materials. There may be ways to make charcoal more similar to coal, although it is highly probable that the amount of forests that would go into creating it would not be viable. Another solution would be to power the coal with rituals, for example, and to simply use the coal as a storage system for the magic. This possibility is of great interest and the object of many experiments, as no good magical storage system exists currently.

A modern peat-forming swamp by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region on Wikimedia Commons

Charcoal by Dati Bendo, European Commission on Wikimedia Commons

Composition

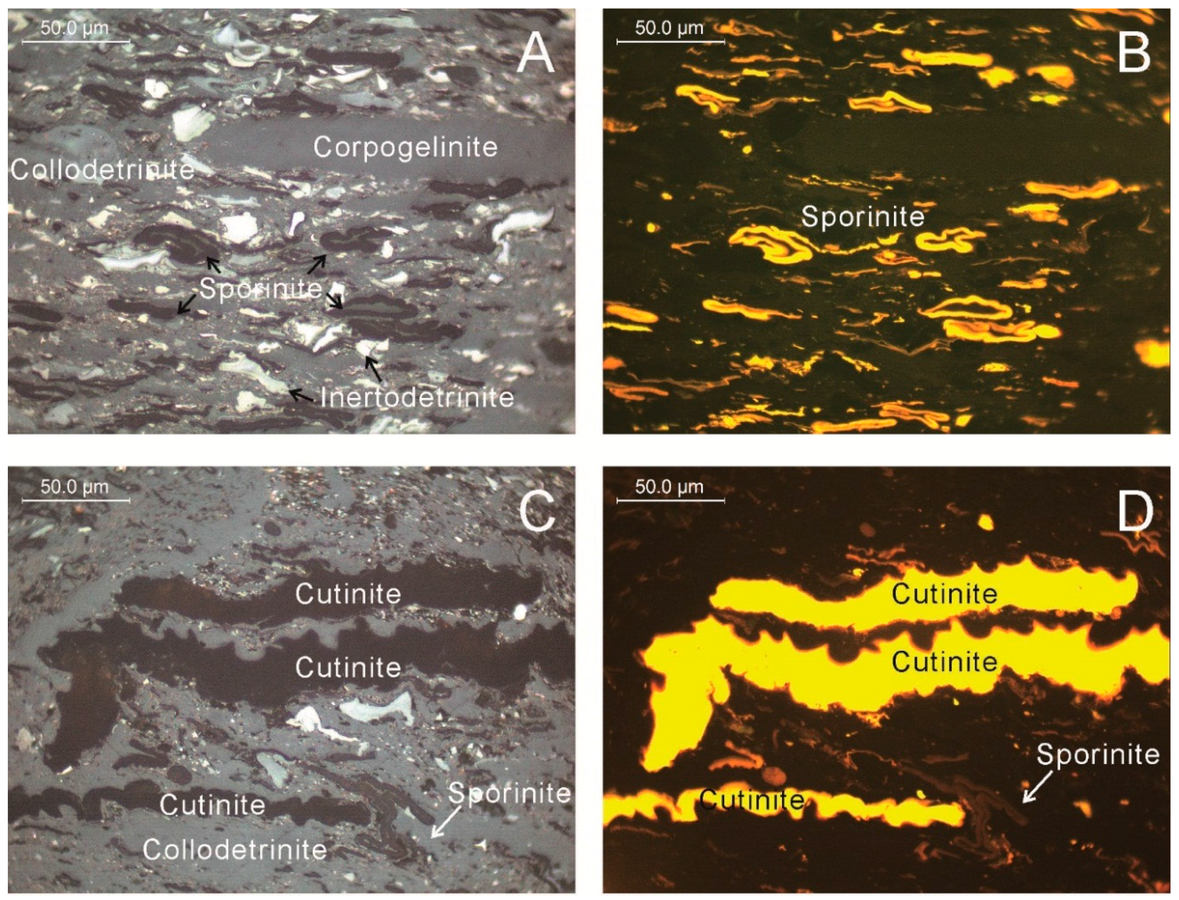

Coal is a mineral made mostly of carbons atoms with some other atoms (mostly hydrogen, sulphur, oxygen, and nitrogen) present in lesser amounts. The coal mineral itself is made of smaller minerals mixed with macerals and water. The difference between minerals and macerals is that minerals are inorganic materials, while macerals are made from organic materials. The exact composition of a coal seam is important, as it defines what type of magic is inside the coal and so what kind of applications it can be used for.

One of the ancient forests that ended up in a coal seam by E-Pics Bildarchiv online, ETH-Bibliothek_Dia_247-03282

Because of its numerous beneficial applications as well as the danger that comes with the exploitation of coal seams, coal composition has been extensively studied in the last century, especially by France, England, the Austrian Netherlands, and Prussia. We have all come up with classification methods and ways to quickly test the coal to determine its properties. We have thus named different types of minerals and macerals that are the main components of coal.

Examples of macerals are:

- Inertinite, formed from degraded plant materials that resulted from wildfire, oxidation due to atmospheric exposure or fungal decomposition. This last one is due to fungi being trapped inside tree resin, such rocks are called funginite rocks. The temperature of the fires also gives different properties to the coal.

- Vitrinite, formed from cellular roots, bark, plant stems and tree trunks. It has a glass-like, vitreous aspect.

- Liptinite, formed from decayed leaf matter, spores, pollen, algal matter, resins and plant waxes.

The ideal would be, of course, to be able to tell which exact species of trees have given which coal seam, as you don't get to mix a murderous carnivorous tree with a peaceful healing ritual without consequences—and haven't I quite some fun anecdotes about that! Unfortunately this is still beyond our measurement techniques for now—and don't go believing all that those imbecile industrialists and naturalists telling you about getting a "feel" from the rocks!

Each type of macerals is also further subdivided into different groups. The exact composition of the coal can be determined by enhancing one's eyesight with magic so as to determine the quality of the coal. Measuring the vitrinite reflectance value also allows one to know the maximum temperature experienced by the coal in its history and so the likeliness of finding oil or gas nearby, both being things that are best avoided for safety reasons as gas explodes and dangerous creatures live in the oil bed feeding of the magic it contains.

I've heard that mining work is very exciting. You never know whether your light is going to set ablaze the whole place or if something will nibble on your extremities if you don't lighten everything like the sun's come to visit you! Not that it really helps against the big ones anyway...

Inside the coal itself, magic is not linked to particular proteins as it is in living beings where it is more often than not transported or stored by iron atoms. Instead, the magic particles are just trapped inside the layers of material. In addition to human's actions or fires, shocks can often release some of those particles—not enough to be useful for the industry, but enough for it to be avoided during transport and storage so as to preserve the quality of the coal. In addition, small children love to play by throwing small bits of coal around or at each other. The small magical shocks it generates can be invigorating.

Nothing like receiving a magical shock into your body to make you feel alive! Since we've got so much coal around here, with the colonel we've been considering using that method against soldiers who can't be awake and ready on time in the morning...

Coal can also be classified in function of how far the coalification process has gone and how much it has been enriched in carbon atoms and magical particles, with the categories being: peat, lignite, sub-bituminous coal, bituminous coal (used to make coke), anthracite, and graphite. However, more concentrated does not always mean better, and the type of macerals inside the coal can be more important for the type of applications made with it.

Bituminous Coal containing different types of macerals by James St. John on Wikimedia Commons

Coal by James St. John on Wikimedia Commons

Coal whose macerals content includes liptinite (~47%), inertinite (~31%), and vitrinite (~22%). Plant microfossils in this coal seam are principally lycopsid tree spores and calamite sphenophyte spores.

Lignite coal by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez on Wikimedia Commons

Anthracite coal by Minerals in Your World project, on Wikimedia Commons

Uses

The steam engine works in the following way: coal is burnt inside a confined area surrounded by metal who has been itself infused with magic by alchemy and runes. During the burning, the magical particles inside the coal are excited in proportion with the temperature reached, and this projects them inside the metal. They can then continue their journey to join up with whatever machinery parts the metal is joined with.

And part of our work as engineers is, of course, to design new machines to exploit this magic. You thought that alchemy was all fancy solutions and smelly herbs? You're dead wrong! Nobody can escape the dominations of the machines nowadays...

Even without burning the coal, the magic is already present inside, dormant. Someone could take a piece of coal, push their own magic inside so as to activate the magic of the coal, and direct it where they want. However, the magic necessary to bypass the inertia of the coal is rather important, and so this is only feasible with small amounts of coal. As soon as bigger amounts of magic become necessary, it is impossible to do it without burning the coal.

Handling coal manually in such a way has been done since at least the Antiquity. Similarly, burning coal to gather the magic has also been done before. The big difference induced by the industrial revolution is the invention of a machine that can gather the magic released by that coal in an efficient manner and transmit it to some other equipment. This has considerably increased the amount of magic that can be reached outside of rituals such as big human sacrifices and so that can be available for regular everyday tasks.

Our researchers always find new exciting ways to exploit the magic of human sacrifices. Such waste we've done by not exploring that magic any sooner all because of the Church's restriction! Thankfully, the revolution and the guillotine once again came to our rescue...

Coal can also be transformed into coke by heating it in the absence of air in a thermally insulated chamber. This coke can then be used in metallurgy to produce cast iron or steel, or for example for roasting malt for beer (using coal itself gives off sulphur vapour that gives it a foul taste). The great increase in the availability of inexpensive iron has greatly helped the industrial revolution.

Iron is everywhere now. Soon whole cities will be made out of it! Thankfully, rich people need to find a new way to differentiate themselves now that it has become so inexpensive, and so they're here to save our tastes!

The gas obtained while burning off coal to form coke can also be collected by distillation. It is then purified and send into tubes throughout cities so as to provide gas for street lighting. This has been done in France since the 1810s, with Paris deciding to replace all of its oil street lamps with gas lamps in 1833. Many over cities throughout the country have also obtained their first gas lighting: Bordeaux in 1825, Nantes in 1828, Lyon and Rouen 1834, Nancy in 1835, Boulogne-sur-Mer and Tours in 1836, Marseille, Le Havre and Saint-Etienne 1837, Strasbourg 1838... In the Southern Netherlands (still independant or conquered by France), the adoption was also fast, with the streets of Lille being lightened with gas since 1825, Gand 1827, Liège and Roubaix 1834, Tourcoing, Louvain, Bruges, Charleroi and Tournai in 1835, Dunkerque in 1837, and Anvers 1840.

So many cities are lighting up as if it were broad daylight! Now we can enjoy endless nights in all safety—and let us all enjoy them as much as we can before all bosses catch up and force us to work endless days...

Gas Lighting is less expensive than oil lighting for the street,s and the constant lights have helped make cities safer. However, the terrible sulphur odours it creates, and the expense are big drawbacks. So far, it has only been used for street lighting, in the house of rich bourgeois (but limited to their entrance hall and state rooms), in theatres as they are always in need of important lighting, in some manufactories whose owners are all too happy to extend the working days, and in some restaurants.

Coke blast furnaces used in metallurgy by Ostrich on Wikimedia Commons

Coke burning by Wikimedia Commons

Gas street lighting by Arpitt by Wikimedia Commons

People marvelling at the first gas street lighting in London by Wikimedia Commons

Dialogue in the caricature

Well-informed gentleman"The Coals being steam'd produces tar or paint for the outside of Houses -- the Smoke passing thro' water is deprived of substance and burns as you see."

Irishman

"Arragh honey, if this man bring fire thro water we shall soon have the Thames and the Liffey burnt down -- and all the pretty little herrings and whales burnt to cinders."

Rustic bumpkin

"Wauns, what a main pretty light it be: we have nothing like it in our Country."

Quaker

"Aye, Friend, but it is all Vanity: what is this to the Inward Light?"

Shady Female

"If this light is not put a stop to -- we must give up our business. We may as well shut up shop."

Shady Male

"True, my dear: not a dark corner to be got for love or money."

The joy of gas lighting by Wikimedia Commons

Exploitation

The exploitation of coal dates from the Middle Age in France, although before the industrial revolution it was only done on a small scale. As types of exploitation of the land, the nobility was allowed to make money from mining, metallurgy and glasswork, whereas in the Ancient Régime it was forbidden for them to make money from manual labour or trade or they would "déroger", do acts incompatible with their status of noble and lose it.

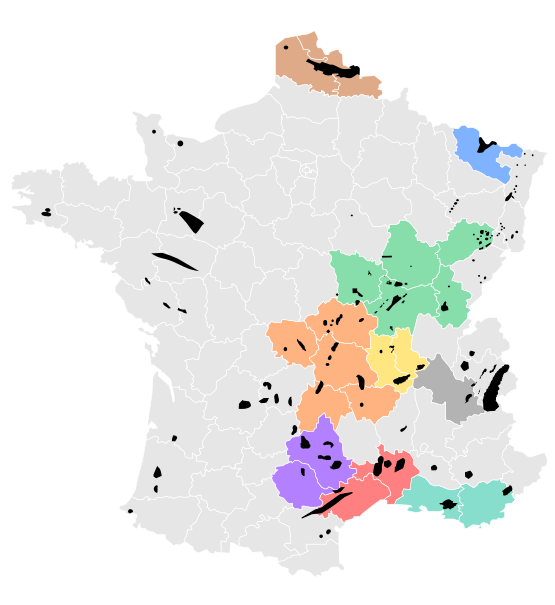

Coal basins in France, in yellow the Loire basin and in brown the North by Superwikifan and A.BourgeoisP on Wikimedia commons

The coal basin of the Loire is the most important in the country, providing 40% of the coal we used, thanks to the numerous places where the coal seams reach the surface. All the coal has been nationalised by a law in 1810, but the state is selling its exploitation to companies. There are around 60 small exploitations in the Loire basin, and all of them are centred around Saint-Etienne.

The presence of this historical source of coal has helped the region develop its metallurgy and its weapon manufactories. The first trainline in France was between Saint-Etienne and Lyon, and it is helping a lot with the transport and trade of coal. Currently, the Compagnie des Mines de la Loire has been gathering all of those small coal exploitations together and it now owns 33 of them, allowing it to produce 85% of the local coal and 1/4 of the national production. It is not a well-loved company locally, and it is the object of bitter critics from all locals regardless of classes.

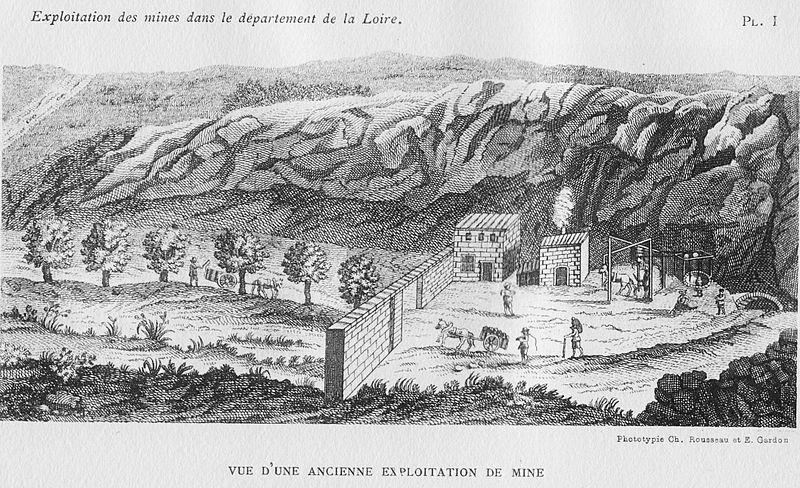

A coal mine in 1780 in the Loire basin by Neantvide on Wikimedia Commons

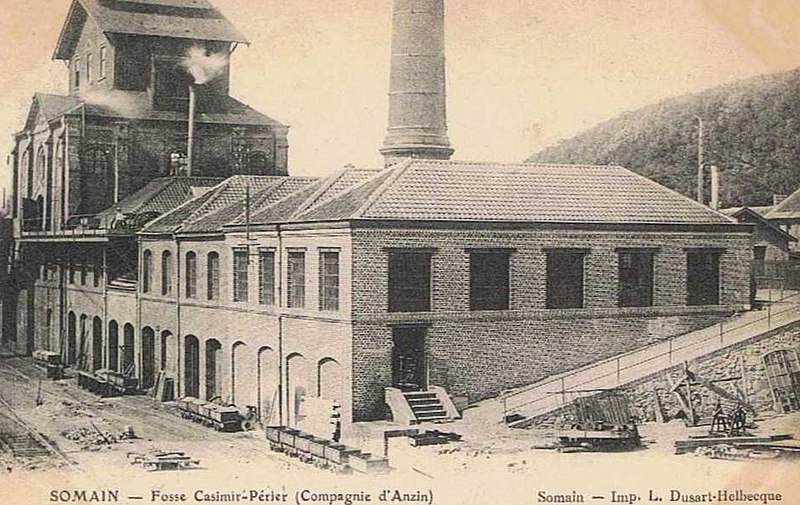

Splendid news for the Nord department! Industrialists in conjunction with the government are investing massively in the creation of new coal mines around the city of Courrières. Those Flemish ought to be happy that we've conquered them now!

— Newspaper clipping

Another important coal basin is located in the Southern Austrian Netherlands. It has been known for a long time that there is coal there, but the coal seams are disappearing underground for some distance before they reached the previous French border. The location of their reappearance near the surface has only been found in 1840. The seam discovered is enormous and its exploitation is quickly increasing pace and could potential catch up with the Loire basin in adecade or two.

Dozens of companies are being created to test the land in the region and find the best place where to start more exploitations. One of the first French trainline has even been built there to join some of the exploitations. Many new miners are needed to work at those mines, and so the companies are building small villages with identical houses to welcome them, the corons. With all this unrestrained growth, the companies care less about safety and investing into their infrastructure than about profit. Such shortcuts are sure to have consequences sooner or later...

Coal Basin in the North of France by AmélieIS adapted from an image by Dosto on Wikimedia Commons

Coal was all the rage now in the region and everyone in Lille wanted to invest in the mines. This was supposed to be their bright future to make them rich after the incessant wars of conquest between France, Austria and England. The first time Adalinde saw one such mine and its workers, she was shocked to realise that their state was even worse than that of the miners in Saint-Etienne. The question was not if an accident would occur or even how soon, but just how bad it would be. She could not help but consider the question from a detached point of view, her eyes coursing over the landscape and tracing the galleries she could guess were hiding underground...

"Everyone knows coal comes from the gigantic sentient and very aggressive trees that preceded us on Earth. Thankfully, humanity has got rid of all of them by now!"-Sergeant.

Now I want a (mad) scientist trying to recreate those trees! :D

I like the idea of those cool trees but I'm not sure if I'll be able to manage to actually talk about them in the novels... However I do have a short story idea for a battle wit a monster in a mine in a semi historical setting and I might be able to place it in that world :D