France has 8 major arsenals: Auxonne (North of Lyon, near the border with the Holy Roman Empire), Amiens and La Fère (both near the border with the Austrian Netherlands), Grenoble (South of Lyon), Rennes (in Brittany in the West), Metz and Strasbourg (near the border with the Holy Roman Empire), and Toulouse (in the South-West). It is where most of the weapons and ammunition are stored and where some weapons are made. In addition, before the revolution of 1789, there are several big weapon manufactories in the country: Maubeuge and Charleville (since 1701 and 17th century respectively, both almost next to the border with the Austrian Netherlands), Saint-Etienne (16th century, South of Lyon), Tulle (1690, in the middle of the country) and Klingenthal for swords (1730, near Strasbourgh and the border with the Holy Roman Empire).

Those areas were not chosen randomly. Indeed, most of them are in the North-East, ancient metallurgic region with many highly qualified workers and ideally located to have an important exchange of knowledge between countries. However, beyond that several factors are important to create a new manufactory: river with strong currents so as to work the mills, navigable waterways helping to transport the production, wood to make coal, and access to metal resources.

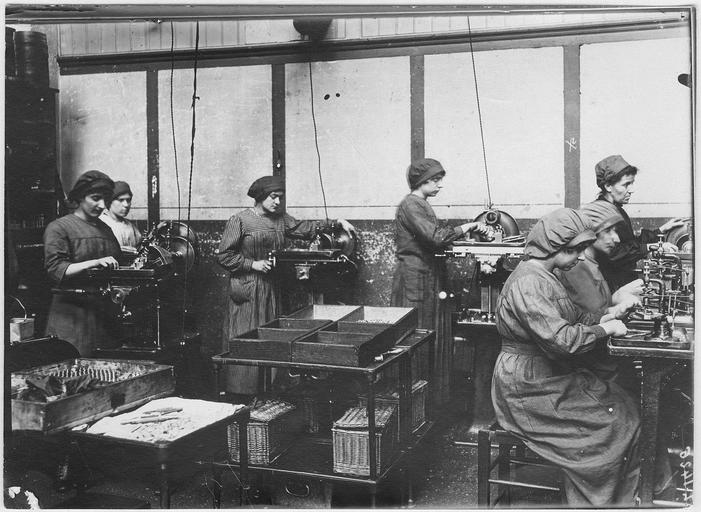

The revolution introduced big changes for weapon manufactories, as an important ideological change was the protection of free enterprise (law Allarde, 1791) and the end of the guilds (with the law Le Chapelier, 1791). As a result, a multitude of small new weapon manufactories appeared: Grenoble, Moulins, Bergerac, Clermont-Ferrand, Roanne, Nantes, Thier, Mutzig, Paris, Versailles... Not all of them are very judiciously positioned, and so many do not survive more than a few years.

King Napoléon reorganised many of those and created new ones in the newly conquered territories: Liège (Southern Austrian Netherlands), Turin (Italy) and Culembroug (Northern Austrian Netherlands). Unfortunately, after Napoleon's death, Austria reclaimed all of those territories, benefiting from all of our military advances while they crippled French armies. Nevertheless, during the retreats, our soldiers left with all the equipment used to forge the weapons, which was costly and difficult to replace.

To avoid further risks,

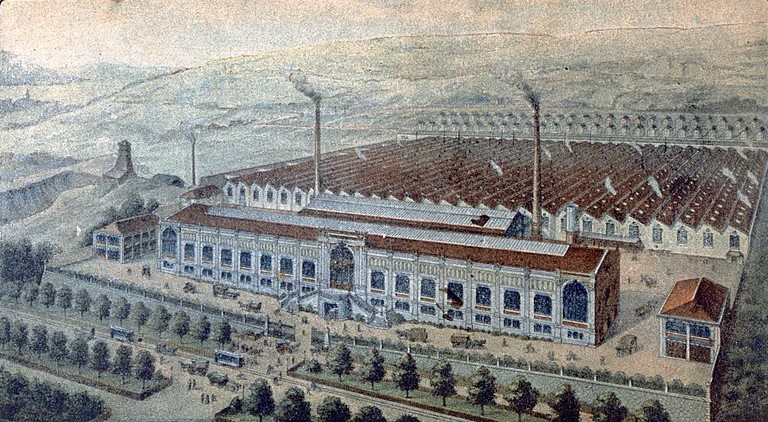

King Lucien Esselin closed the manufactories of the Maubeuge and Charleville in the North, and the manufactories of Klingenthal and Mutzig in the East, and he had a new state-owned manufactory built in Châtellerault in the middle West of France.

Saint-Gervais, a very ancient canon foundry located South of Lyon was closed in the early 18th century. It was reopened during the revolution, but the furnaces had to be made functional again and adapted to the technological changes, and so the manufactory has only recently restarted to make canons. It being close to the

military alchemy manufactory in Lyon and the weapon manufactory of Saint-Etienne, Saint-Gervais has also been converted into a mainly experimental manufactory rather than one focused on production. Those three sites make up the research triangle of the army.

Thus, the current major manufactories, all owned by the state, are: Saint-Etienne, Tulle, Saint-Gervais, and Châtellerault.

And I can tell you that nobody was happy when the manufactories closed! Those towns and their surrounding lost all of their activities, and of course no one was going to accept to move to Châtellerault when they had their whole family and small plot to cultivate here! Politicians should remember to never anger those in charge of the weapons... Those idiots thought they were breaking a strike of lowly workers when in fact they were facing a fully armed battalion!

OOOH a quote from Adalinde! nice to get a peak into her mind.

I should do that more since she is the MC, shouldn't I? But the tone is always more serious with her...

Well the Sergeant is a nice narator. there's no harm in saving Adalinde for the story.