On the Palatine Ear and the Palatine Tongues

General information

The Polychordate palate has, since the colonization, been subject of scientific discourse due to its peculiar morphology and the large variety of phylogenetic models that have been presented so far as to describe its origin and biological ineptitude to variate so little in the 490 million years since its appearance in the fossil record with the first members of the phylum. Of major importance is the Palatine Ear which, in the span of polychordate evolution, rarely moved from its ancestral position in the palate and barely changed in structure in the last 450 million years. This article will explain both the Ear, Palate and the types of palatine tongues seen across Ichthyomorpha, providing examples both modern and ancient along the way to show the presence of these structures in the fossil record too.The Palate

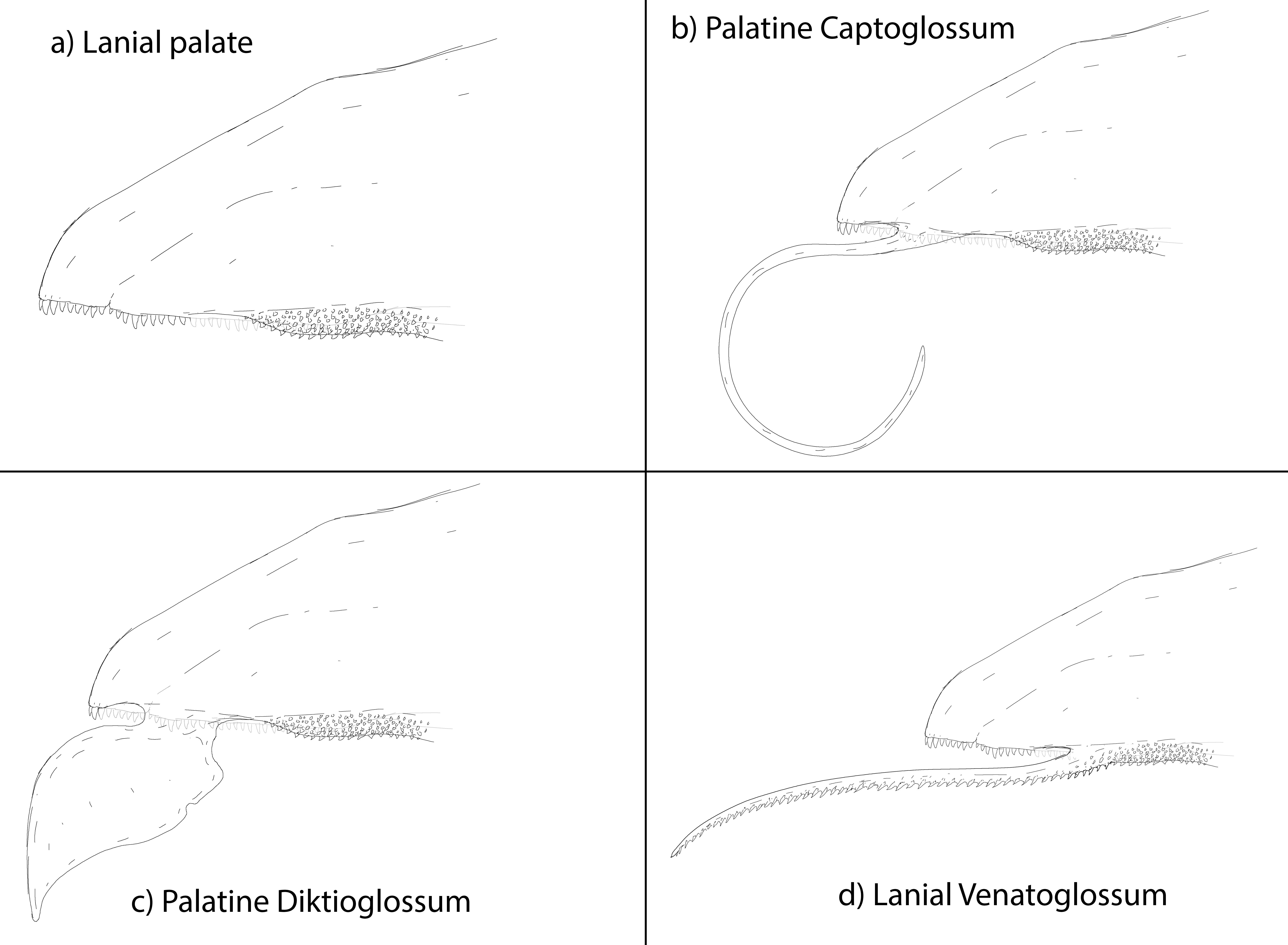

figure 1 The Ichthyomorph Palate (Figure 1) can be divided into four main sections: -The outer section, the dentary, is composed of Dermoskeletal and Endocranial teeth (distinguished by their origin), this outer area of the palate is the one most used in predation as the teeth, just like on Earth, are used to grab onto prey (figure 1.a, 1.a.2). -The Palatine Ear, expanded upon later, the main hearing organ for Ichthyomorphs (figure 1.a.3) -The Soft Palate, composed of two sections, one akinetic, where the palatine tongue grows out of and one kinetic, called the Palatine lip, which is used to seal the Palatine ear while the animal eats (figure 1.a.4) -The Lanial Palate, the innermost section of the palate and the one designated to mastication alongside the Sphaera Lania, which will be explained in further detail in another articleThe dentary

The outermost section of the palate, composed of the two rows of teeth. The teeth are differentiated into two categories based on their origin: -Dermocranial teeth -Endocranial teeth The Dermocranial teeth are the outermost row and originate from the Dermocranium (the cranial armour), they are lodged into the cranial plating and are usually characterized by deeper roots and thicker dentine layers, making them the preferred hunting instrument for animals like the Living Spear. Dermocranial teeth are also commonly used as display structures in several genera spanning most of the Ichthyomorph superclasses like it can be seen in the Hetherian Ocean King-Northling. Endocranial teeth grow onto the Splanchnocranium and originate from the ectomesenchyme of the neural crest in the embryonic stage. These teeth are lodged in the motile gum inside the mouth which, in some animals like the Square-Headed Dignathophagus, can extend well beyond the first row's reach. The Endocranial teeth are made of Calcium phosphate, making them easier to regrow once they wear out compared to the much more energy costly teeth of the dermocranium. Due to the low Calcium contents of the oceans, most Ichthyomorphs will ingest their own teeth to reuse the material to create new ones, with some animals actively looking for shed teeth on the seafloor to use as calcium packets.The Palatine Ear

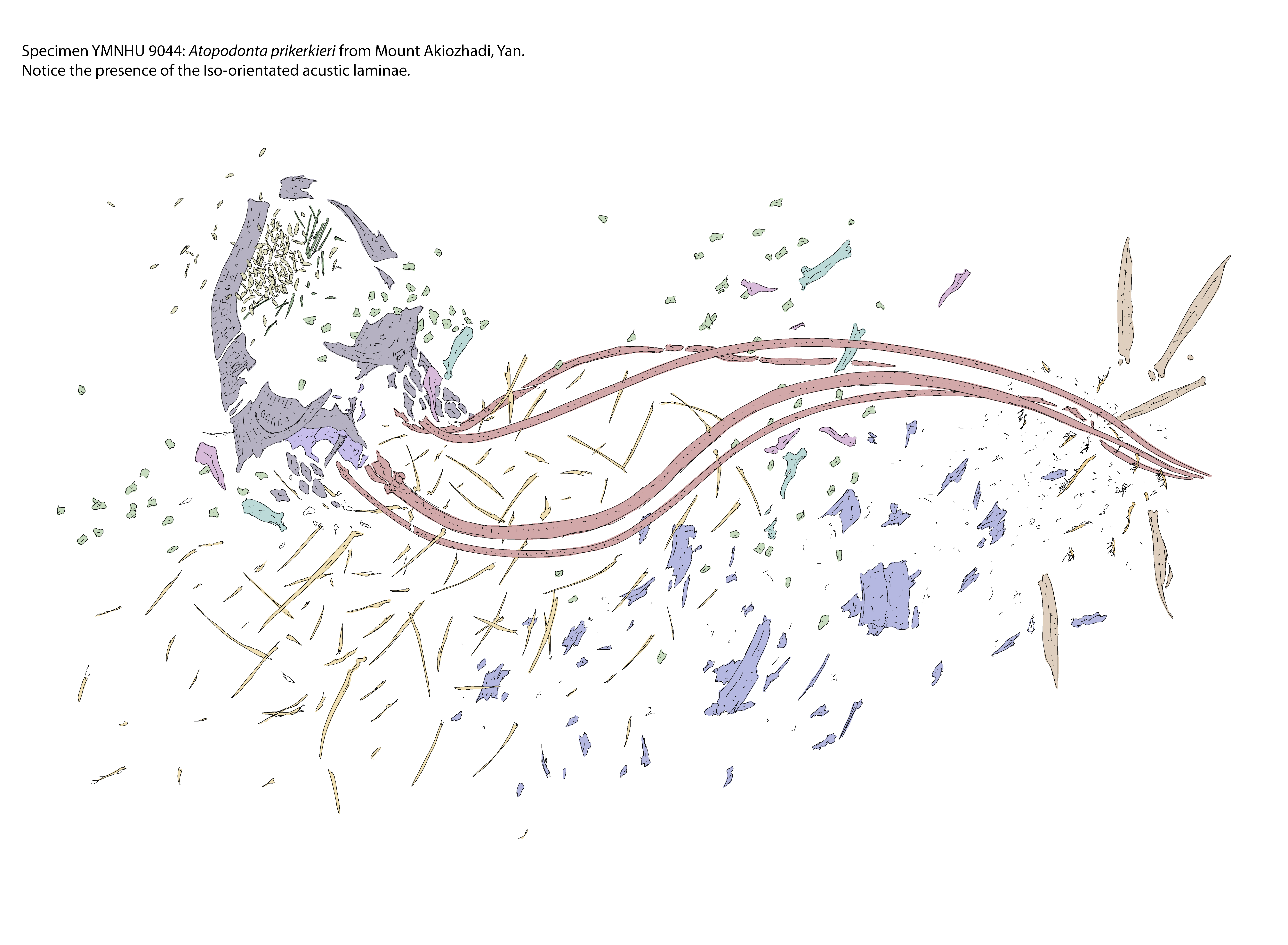

The palatine ear is perhaps the most interesting part of the palate anatomy. The Ears are openings in the palatal structure of the cranium and are composed of thousands of millimetre thin Laminae which capture even the slightest vibration in water (figure 1.b). The Acoustic lamina (figure 1.b.1) grows from a support and transport structure known as the laminal shaft (figure 1.b.2) which, thanks to its specialized internal structure and liquid, conveys information gathered from the lamina to the Palmoreceptors (figure 1.b.3) at their base, from there the signal is sent to the cephalic brain, which will be able to interpret it properly. These laminae grow parallel to one another in a bundle (figure 1.c) known as Laminal fibre; the laminae themselves get constantly repaired during the organism's life to adjust for wear and tear. The first-ever known proof of a laminal structure in Ichthyomorphs dates back 450 Million Years and is visible in a preserved specimen of Atopodonta prikerkieri from Yan (pictured below). This animal, contrary to more modern Ichthyomorphs, had both teeth and Ears loose into the radular tongue, hence why, in the preserved remains, the two elements appear so chaotic. figure 2 Zoom in onto the Laminae and teeth: This simpler disposition of the Ear is thought to come directly from their ancestry which, without a mouth, had the acoustic organ on the bottom of the head. In primitive ichthyomorphs like A. prikerkieri it's still unsure which are true teeth and which are dentitions of the yet to evolve Lanial palate, possibly because the distinction was yet to emerge at this stage. With the reduction of the Radular tongue into the more contained palate, the ear lodged into the cranium like seen in later forms (figure 7)The soft palate and the palatine tongues

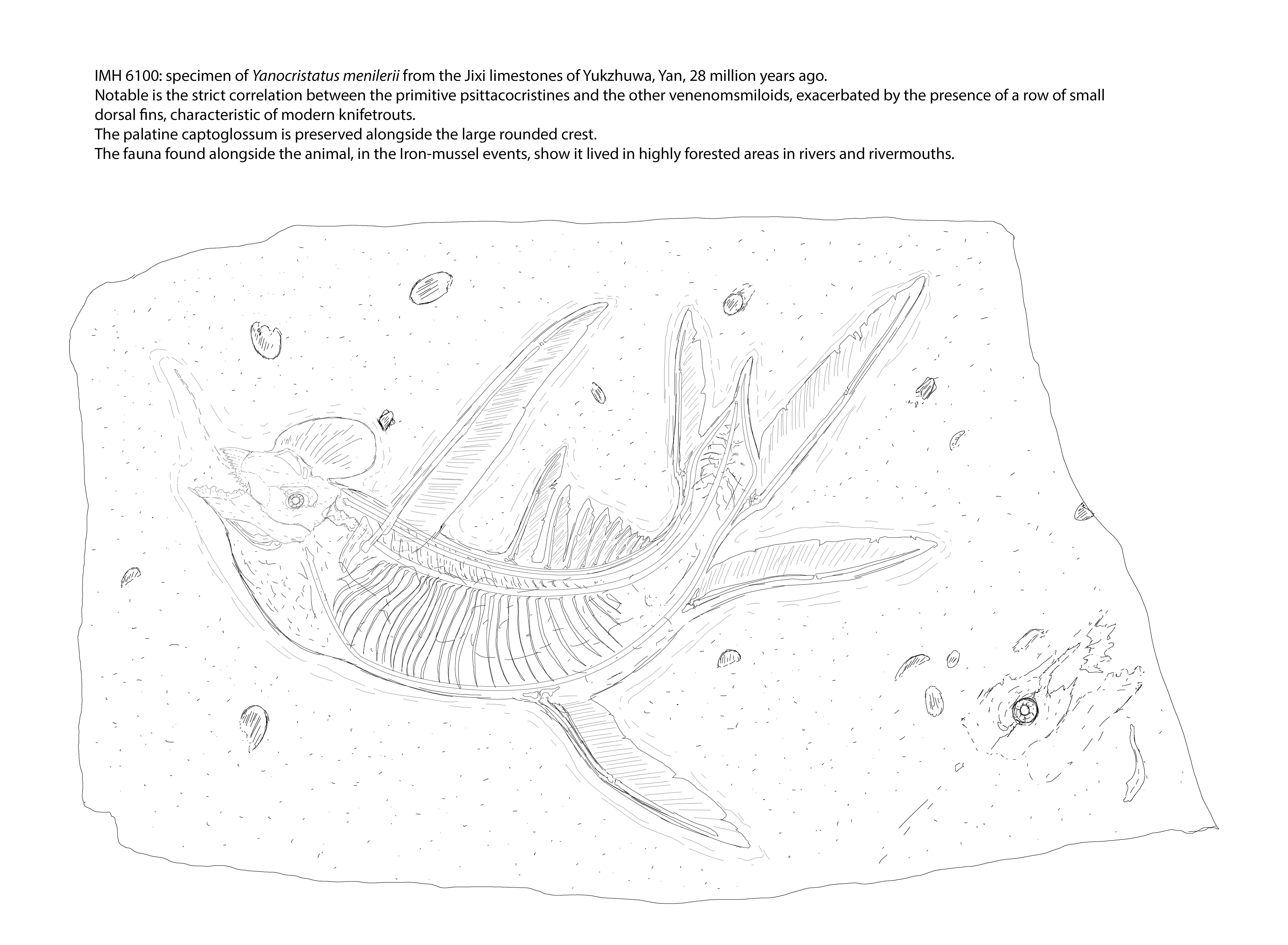

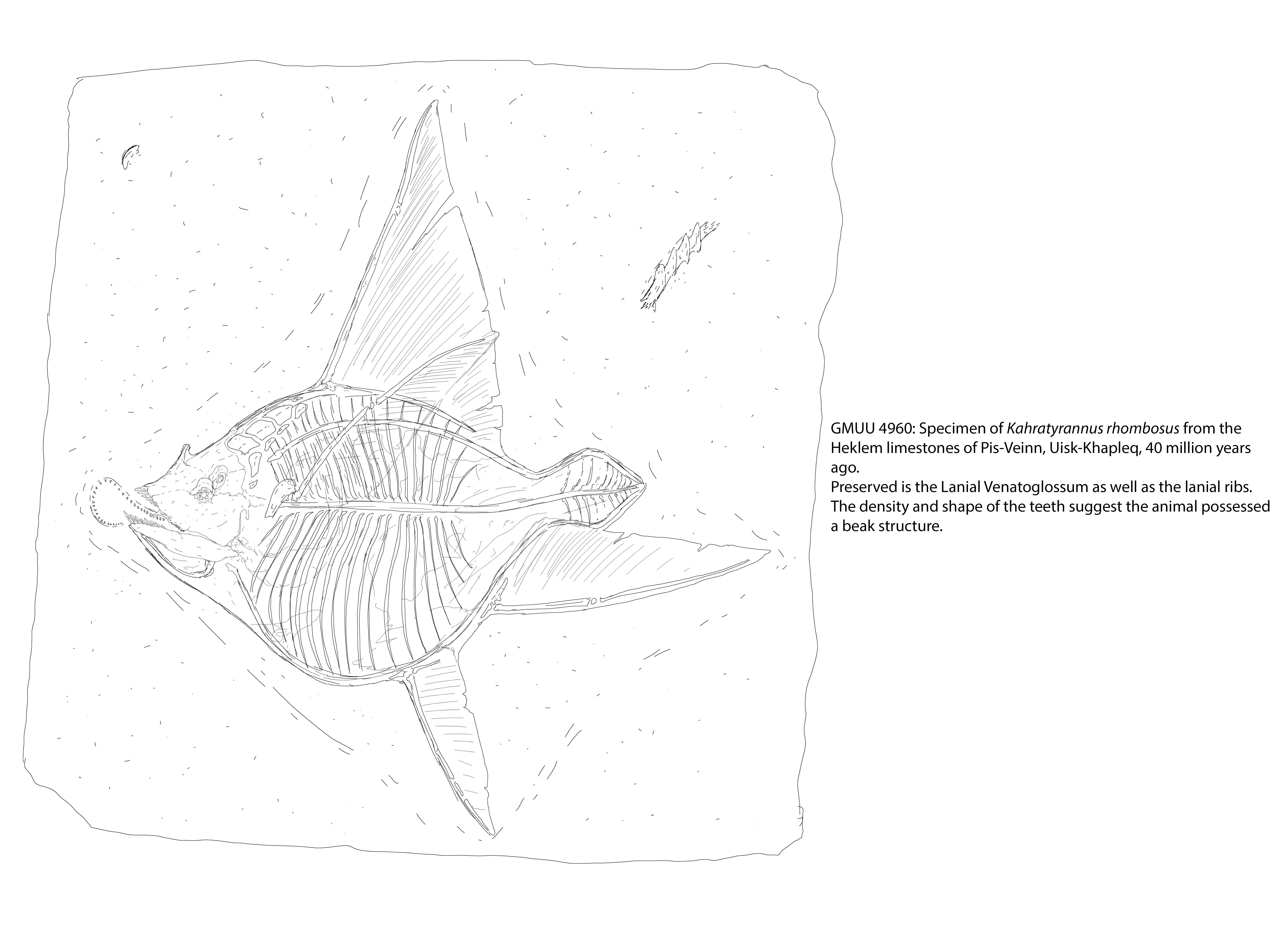

The soft palate is that section of the upper palate characterized by a mostly muscular structure which closes the mouth structure and covers the palatine fenestrae and ears. The soft palate is divided into two parts: -the Palatine Labia -the akinetic palate The Palatine Labia are the kinetic sections of the upper palate and are composed by lip-like structures in charge of protecting the acoustic laminae while the animal eats. By sealing up the Ear, the animal reduces its hearing capabilities in exchange for the ears being protected from food scraps that could harm them. The palatine labia is largely the same across all Ichthyomorphs, with no major differences across the superclasses. The Akinetic Palate is the section of the soft palate that closes off the upper cranium and isn't tied to hearing functions. This part of the palate, however, is the base onto which two of the three main typologies of palatine tongue grow. image 3 The Palatine Tongues are divided into three main morphologies: -The Palatine Captoglossum (figure 3.b) -The Palatine Diktioglossum (figure 3.c) -The Lanial Venatoglossum (figure 3.d) The Palatine Captoglossum is the most common among the three types and grows from the akinetic palate like a long, prehensible and retractable tentacle-like appendage used mostly by herbivorous animals to manipulate objects and bring food to the mouth. This tongue type is most commonly seen in animals like the Cockatielfish or the Sand-striped Twinfish. Although it is known to be much older than that, a particularly well-preserved example of this tongue morphology has been observed in a fossil of the Galeocristatoid, the Yanocristatus menilerii (figure 4). figure 4 The Palatine Diktioglossum is very similar in origin to the previous morphology, however, instead of being tentacle-like in shape, it has a much broader prehensile surface that extends to the point of being broader than the mouth itself in some species. This morphology, the rarest among the three, is used by both herbivores and carnivores, although in a very similar fashion. The extended fan is able to encapsulate food and bring it directly inside the mouth, very useful when foraging for fruit or small organisms. Like the previous tongue type, the Diktioglossum originates from the akinetic palate. Once much more common than in present times, the tongue type has been observed in the fossil record in some Lagerstätte around both hemispheres, below one such example as seen in a fossil of a Diktiognathus atrox, a prehistoric relative of the modern-day Morsvectorids. figure 5 The Lanial Venatoglossum is the second most common tongue type. It originates from deeper into the Lanial Palatine (explained below) and develops the dentitions of the latter along its entire length. Having a similar shape to the Captoglossum, this different tongue type is mostly used by predatory animals as it can retract directly into the lanial apparatus without suffering any type of damage due to possible unwanted contact with the Sphaera Lania. This tongue type, too, has known fossil representation in sites of exceptional conservation as seen in this fossil of Kahratyrannus rhombosus figure 6The Lanial palate

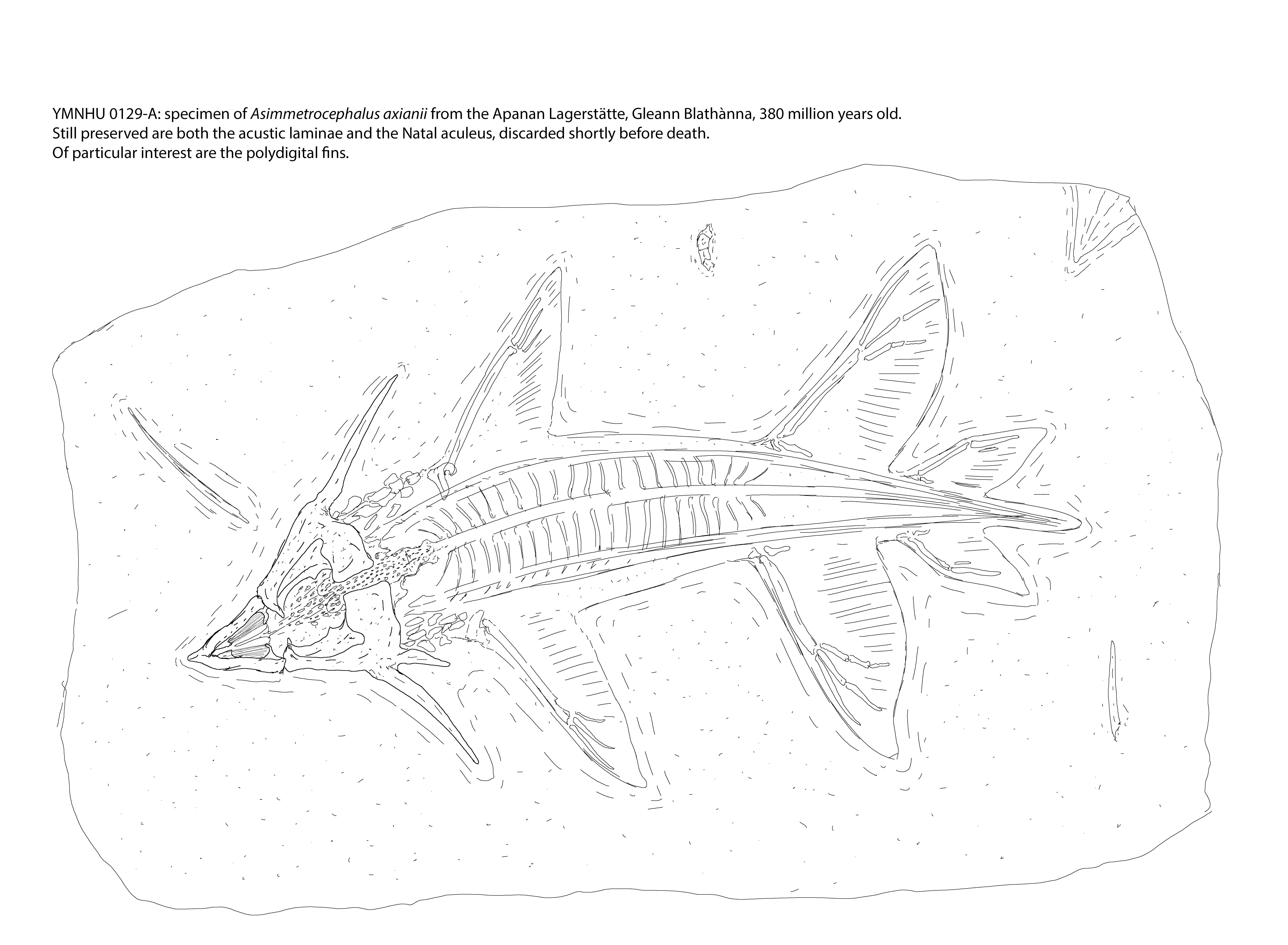

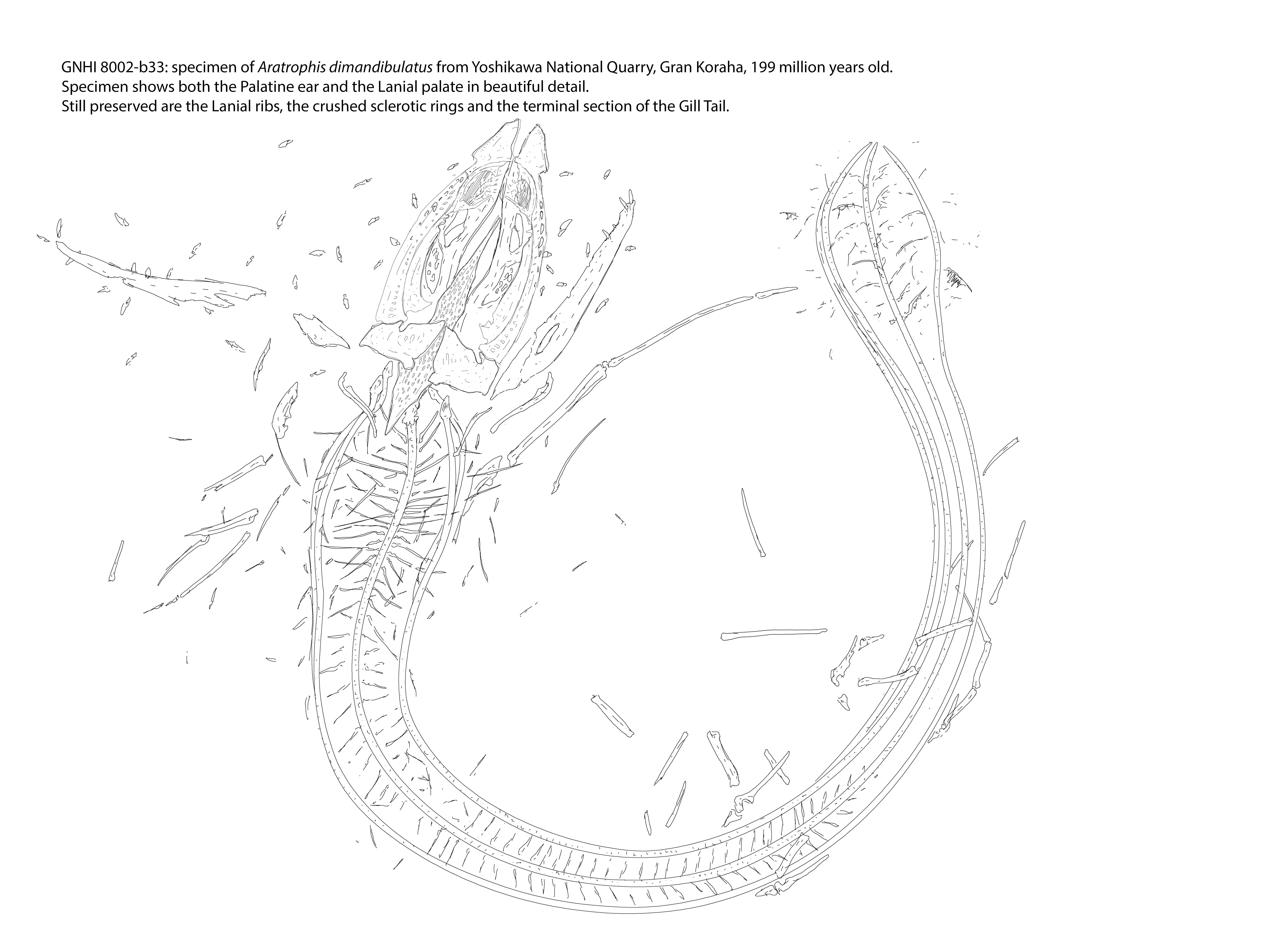

The Lanial Palate (figure 3.a) is one of the two major organs in charge of mastication. It derives from the Radular Tongue and is composed of a large bony plate on the lower half of the palate, the Lanial Plastron; this plate acts as the hard surface onto which the Sphaera Lania presses upon to grind down foods. The Lanial Palatine is covered in hundreds of small dentitions or lanial teeth which are constantly consumed and changed through the animal's life. Its natural history is quite well documented too, with proof of its gradual formation in many fossils specimens from around the globe. figure 7 This fossil specimen of Asimmetrocephalus axianii shows a transitional stage from the Radular tongue to the Lanial palatine as shown by the restricted zone and disposition of the lanial teeth, which demonstrates how these animals were reducing the size of the radular tongue in favour of more precise mastication, change probably prompted by a more varied and specialized osteophyte diet since the inception of Ichthyomorpha as a subphylum. figure 8 This almost 200 million-year-old specimen of Aratrophis dimandibulatus, on the other hand, shows an already well developed Lanial Plastron with all the Lanial teeth in place. The once specular appearance of the lanial apparatus as a whole can sometimes be seen in the fossil record too, showing a time before the Sphaera Lania's development.Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

The art and figures that accompany these anatomy articles are always so good!! <3

Thanks so much! ^^