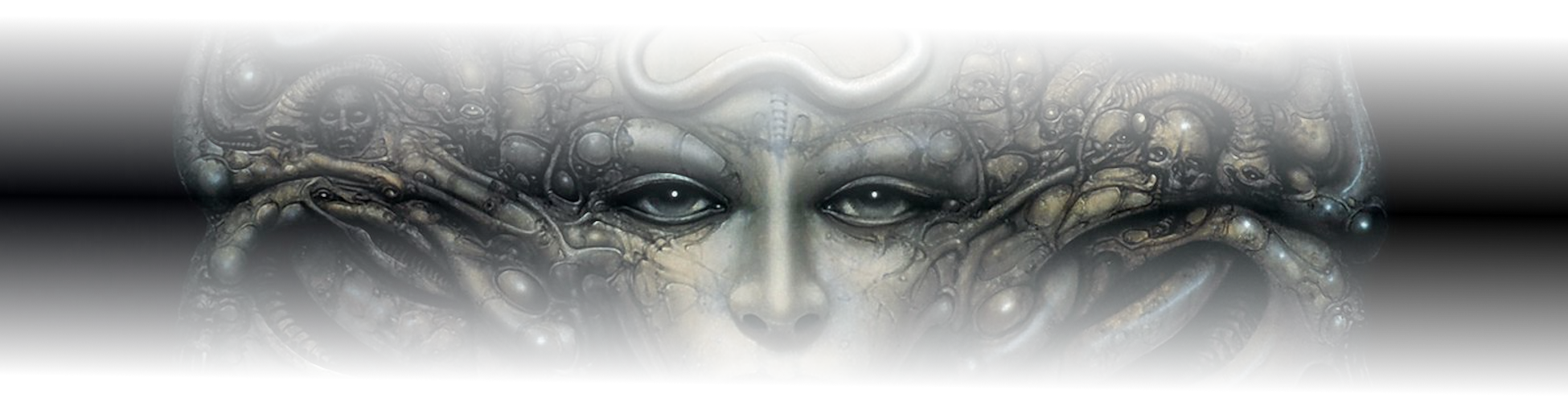

Gothic Space Opera

Before we even begin to consider the setting itself, we must first concern ourselves with a definition. Just what is a “gothic space opera”? Some may be yelling “Warhammer 40,000!” from atop your personal skull throne, but while I will suggest that while Warhammer certainly carries that vibe, it is far closer to science fantasy – simply dialed up to 40,000. Others might claim it’s spooky Star Wars, but again, I think this misses the mark.

According to Merrium-Webster, a space opera is, “a futuristic melodramatic fantasy involving space travelers and extraterrestrial beings.” That’s not bad, but not all space operas have aliens; take the mothership itself – Foundation. Going all the way back to I, Robot, Isaac Asimov repeatedly refused to incorporate extraterrestrial beings in his 14-book masterpiece, but most any of those books could be called space opera. Wikipedia calls a space opera, “a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, melodramatic adventure, interplanetary battles, as well as chivalric romance, and often risk-taking.” This is closer to what we need. I’d go further and suggest that a space opera is a highly melodramatic story, often set in the future that emphasizes grandiose conflict, interplanetary adventure, and chivalric romance.

That’s all well and good, but I’m not making a space opera. I’m making a gothic space opera. Does that mean we just need to dress our setting in black, powder its skin, and put black nail polish on it? No! Wrong kind of gothic! When I say “gothic”, you say, “Melmoth the Wanderer”. When I say “gothic”, you say “The Castle of Otrato”. Haven’t read them? Do it. They are fantastic. They are what soil from which Edgar Allen Poe sprouted. They are gothic literature. And that is the kind of “gothic” I am speaking of. But did you catch that? I still haven’t told you what “gothic” really means.

Gothic literature is a style of literature that springing from the romantic movement in British literature that, rather than focusing on a withdrawal from society and a return to nature, aims directly at what humanity has become. It revels in the mundane grotesqueries that are everyday life. It cherishes the sublime suffering that pervades every moment of every day. It is the foundation of the entire horror genre without itself being horror, and it is all at once a style, a mood, and a literary movement. It can, perhaps, be best summarized as a genre that concerns itself questions of existence through the juxtaposition of the sublime and the grotesque. Gothic stories often feature high melodrama, powerful – if not indomitable – antagonists, elements of the supernatural, damsels in distress, and always a stark contrast of the grotesque corruption against sublime purity.

So did you notice? Five hundred words and still no sign of a definition. But I do believe we are much closer to one than when we began. In fact, the astute reader might notice that neither list of characteristics or descriptions – that of space opera and that of gothic literature – are mutually exclusive. In fact, they both involve melodramatic stories, epic antagonists, and conflict. This suggests that we can, indeed, marry the two, and that is just what we will do. So before we get too ahead of ourselves, let’s leave ourselves a definition:

A gothic space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that revolves around the melodramatic telling of stories concerning grandiose conflicts between powerful antagonists and clearly inferior protagonists and involve interplanetary travel, chivalric romance and risk-taking, elements of the supernatural, and themes of purity and corruption.

Elements of a Gothic Space Opera

Literary elements - e.g., characters, conflicts, mood, pace, style, tone, etc. - play an immense roll in shaping stories, but they are are rarely addressed in game books except to mention things words like “episodic” or “picaresque”. They overlook what can be added by careful use of point of view, narrative voice, and careful manipulation of narrative time, and they don’t directly address many other literary elements. This section will examine several elements in the context of gothic space operas and how they might influence later design decisions.Narrative Mode

Let’s talk about narration. There is a strangely propagated myth concerning this subject as it relates to roleplaying, so let us begin by breaking those down. Games often treat the GM as The Narrator – indeed, some even call him that – and the players are characters or player characters or PCs. The implication here is that the GM is the sole narrator, and the PCs do not fill this function at all. Instead, players are just their characters; which, in turn, leads to discussions of meta-knowledge and the like. But this approach is not ideal. The reality of narration in roleplaying games is that every person playing shares in the narration. The GM narrates the setting and non-player characters, yes, but the players each narrate the thoughts, feelings, and actions of one of the main characters in the story. I would go so far as to suggest that the GM actually spends less time narrating than do the players! With this in mind, I will begin our look at the interaction of narrative point of view, voice, and time.Point of View

Narrative point of view may be one of first-person, second-person, third-person, or alternating. Typically, in literature, point of view is kept uniform throughout the work, but in other media, it can alternate. In my years of gaming, I have seen all three points of views used in the same session, even, but I think this is primarily because gamers are not mindful of how careful use of point of view can affect and color the game. So let’s take a look at them . . . out of order. Second-person point of view is used when the narrator addresses the characters directly as “you”. This is common in music lyrics, some poetry, and habitually used by GMs everywhere when dictating character actions. This suggests, however, that the players are the character, when we can see from our previous discussion that the players are actually co-narrators. This tends to pen players into using only the first person when describing their PCs’ actions. For this reason, I strongly suggest GMs avoid using a second-person point of view. Next, let’s take a look at that first-person point of view, a view that suggests the narrator is also a character in his own story. It sees a lot of use by players and has its place, but just what is that place? A first-person point of view assumes a narrator is conveying what the character is thinking and feeling directly, often through the filter of the character’s perceptions and biases. By its very nature, a first-person point of view cannot be objective or omniscient (see Narrative Voice, below). This last limitation prevents the player from asserting how the setting views the character – something players often want to do – and requires that a player remains “in character” for extended periods of time. The latter isn’t necessarily detrimental, but the breaking character can be jarring in a genre where atmosphere is crucial. Third-person point of view is probably the most pervasive in literature, and sees extensive use in other media, too, for its ability to present the narrator as an uninvolved observer. In fact, the narrator is not required to even exist in the setting. This point of view often rears its head in massive prologues that set up adventures, but it is just as present in a brief description of a town, monster, or non-player character. While it can reveal a great deal about characters, it lacks the personal touch that first-person does. It does, however, afford the narrator far greater freedom of voice. This can allow a player to ascribe attitudes and perceptions about his character to NPCs, and better seat his character within the game world. As we will see in our discussion of narrative voice, third-person especially presents itself as a powerful tool for GMs. Considering these three options, I will now do that thing that usually annoys people. I’m going to tell you that we will support a fourth options: an alternating point of view. Because second-person doesn’t really treat our players the way we want to, that will not be recommended; however, it can be extremely useful for any person at the table to slip between first- and third-person. First-person may be used when roleplaying out interpersonal interactions, or otherwise trying to convey personal thoughts or emotions, and third-person should generally be used to set the stage and dictate what is actually happening in the world. With that said, I, personally, prefer to remain in third-person and use the character’s actions, description, and dialog to convey what a character is feeling and thinking. But that’s just me; first-person definitely has its place at the table, when used to its strengths.Narrative Voice

Now that we know we will use either first- or third-person, we must decide on the narrator’s voice. This will likely shift based on circumstances and will likely differ between players and GM. For instance, it would be natural to assume that players almost exclusively use character voice, in which the narrator ceases to be an unnamed entity and becomes one of the characters in the story. While pervasive among players, this is also typical of GMs depicting NPCs. A variety of third-person voices are available for the GM, and possibly the players. Third-person subjective, sometimes called “over the shoulder” perspective should generally be avoided by the GM to help maintain a sense of uncertainty, but it does fit players quite nicely. It could be argued that in a game where players use third-person point of view, they are actually using third-person subjective; a rather famous example of such a voice is the A Song of Ice and Fire series. Third-person objective presents events as factually as possible without interjecting any feeling or emotion into it, thus making it ill-suited for such a melodramatic style as gothic space opera. However, third-person omniscient voice not only bolsters the narrator’s reliability, but it also allows him to retain his own personality. Of these, we will assume that players will either use character voice or third-person subjective voice, and GMs will use omniscient voice. This lets players inject as much of their characters’ thoughts, feelings, and motivations into the story as they want, and the GM can remain a reliable narrator while retaining a personality. On occasion, the GM may switch to third-person subjective during interpersonal interactions where he needs to inform the players of information the PCs might know.Narrative Time

Narrative time refers to the grammatical tense used to tell the story. And with that one sentence, I probably just lost half my readers, but this does matter. Choosing a tense that suits the game’s needs and sticking with it provides a subtle layer of consistency that helps everyone’s thoughts fall away from the task of interpreting what everyone is saying. Instead, people can more easily just absorb the flow of information without the distraction of parsing it. So what narrative times are possible? Unsurprisingly, there is past, present, and future. Immediately, we can rule out the use of future tense because no one can predict just how the dice will fall. As for the other two, I have heard both and personally prefer present tense. Past tense can be difficult to maintain and brings a degree of finality that does not always suit a roleplaying game where events are uncertain until the dice hit the table. It does, however, lend a very literary feel. If a particular gaming group can cultivate this while mitigating its drawbacks, past tense can be quite well suited for the needs of a gothic space opera.Narrative Structure

Narrative structure is about story and plot: the contents of a story and the form used to tell the story. Story refers to the dramatic action as it might be described in chronological order. Plot refers to how the story is told. Story is about trying to determine the key conflicts, main characters, setting, and events. Plot is about how, and at what stages, the key conflicts are resolved.– Narrative Structure, Wikipedia

That may be a lot of words, but it all boils down to this: narrative structure is how the story is told. Let’s take a look at each of the four main categories – linear narratives, nonlinear narratives, interactive narration, and interactive narratives – with an eye toward our medium, and see which ones best suit our needs.

- Linear narratives tell a story in chronological order, and while they may feature flashbacks, these eventually return to the “present time” and continue onward to a conclusion. They are the easiest to follow and probably the most common.

- Nonlinear narratives present events out of chronological order in a way that does not follow the flow of causality. The most famous example of this is probably the movie Pulp Fiction (1994) in which three related stories are told simultaneously and out of chronological order. This can make the story difficult to follow in a movie, let alone a tabletop game. Generally speaking, this is not an ideal choice.

- Interactive narration involves a linear narrative that is driven by the user’s interaction. This is typical of many modern video games that require the player to accomplish one task to move the story forward and open other parts of the game. In a roleplaying sense, this would be closest to a so-called railroading adventure or campaign.

- Interactive narratives are similar to interactive narrations, except the user actually decides how the story develops rather than simply rolling forward along the only possible path. At its extreme, this is the archetypal “sandbox” game.

Characters

Characters refers to the types of, well, characters present in a story. It encompasses ideas like flatness versus roundness, static versus dynamic, and stock versus individualized. There is far more to building characters than just this, but these should suffice to address our needs. Flat characters are uncomplicated and two-dimensional, while rounded characters exhibit nuance and depth. Neither of these is explicitly better than the other, overall; pulp fictions have made their bread and butter off of flat characters for decades. But let’s take a look at the needs of our chosen genre. We need high melodrama, chivalry, action, and conflict. Also, gothic novels typically use characters with a major defining flaw that is the source of their ultimate downfall. In fact, gothic characters are quite flat in their embodiment of their flaw, be it pride, lust, avarice, etc. Space opera also tends to use flat characters but focuses more on their dramatic role than thoughts and feelings. Thus, we will follow suit with fairly flat characters, each of whom will have a major flaw and otherwise fill a dramatic role within the story. Static characters are those who never change throughout a story, while dynamic ones do. Consider Legolas versus Samwise in Lord of the Rings as examples of each. In gothic literature, characters don’t change much, and when they do, it is usually through corruption. Conversely, Space Opera is often about the Hero’s Journey from naïve youth to experienced saver of worlds. These two are at odds, so let’s see what about each would best suit our needs. Dynamism requires a degree of screen time to show growth that static characters do not, so what does this time cost buy us? We can watch a slide into corruption, a growth into the person one needs to be rather than the one he wants to be, the destruction or abandonment of ideals, etc. In other words, drama. But being static has its perks, too: such characters are predictable and easily followed with little need to update them over the course of a story. I am going to suggest that player characters be dynamic in the ways I mentioned above, while NPCs tend toward the static side of the spectrum. The latter doesn’t preclude redemption stories for table favorites, but this is gothic space opera – we aren’t here for happy endings. Lastly, we will address stock characters versus individuality. To an extent, this mirrors our discussion of static versus dynamic characters – stock characters are easily understood, fill well-defined roles, and get the ball moving quickly, while individualized characters require extra screen time to explain. Because both the gothic genre and space opera make their living off of stock characters, I will say that player characters should find their origins in stock characters and grow from there through defining flaws and character growth. Non-player characters should probably just be stock characters unless they grow into a major supporting character.Dialogue

I won’t say much about dialogue because this will always be tainted by the cultures and subcultures to which the individual players and GM belong. I will say that it should be as realistic – to the group at the table – as possible, and above all, be consistent. If the average person uses so much slang that Anthony Burgess would be envious, then most characters need to maintain that all the time. I will say from experience, choosing a non-natural speech style for dialogue can become onerous when you’re forced to try to maintain it for long periods of time. So really, just make certain that everyone can keep it up and have fun doing so.Mood

Mood is the feeling that a work produces within the reader. This one will be tricky since we cannot force a participant to feel any one thing. We can, however, decide what we want them to feel and look at ways to create it. We know that space operas will people with excitement, awe, and wonder; while, gothic novels inspire a sense of anxiety, fear, and horror. None of these things look to be contradictory, so that’s our ultimate goal – to create a feeling of excitement, anxiety, fear, awe, wonder, and horror within the players and the GM. There is an essay floating around about how gothic literature is a study in the juxtaposition of the sublime and the grotesque. If I find it again, I will link to it here, but the idea is that the novel builds up an idyllic image of beauty and purity just to smash it with some horrible malformation. To that end, I think that setting terrible events against a backdrop of beauty, wonder, and a sense of vastness within the setting will hit this nail on the head. The players attempting to reconcile the two simultaneously creates the sort of cognitive dissonance that embodies the type of horror present in gothic stories. Much of this will be accomplished through diction and supported by setting elements. Excitement is often seen as a good thing, but it can also be described as agitation. This is a close cousin to anxiety. Combining the sort of excitement we see in space opera with anxiety produces something more akin to suspense. Mixing in a dose of fear brings provides a sense of thrill. For this reason, I think we should be looking at using action and threat of near-certain failure to drive a suspenseful and thrilling atmosphere. This will require over-the-top adversaries, high stakes for the characters, and plenty of space within which to act.Pace

Pace refers to the speed at which the story is told. Both genres, and indeed, any good storytelling dedicates more time talking about important events than unimportant ones. That’s why 80s action movies use montages to gloss over months of boring training and preparation as a justification for the action that is about to take place. And it’s why we see long monologues during final showdowns, lots of posturing, and finally a fight scene with tons of stunts and slow motion during the climax. The storyteller is allocating more temporal space to the important events and minimizing the space occupied by unimportant ones. There isn’t much to say here as it applies specifically to gothic space opera, except to discuss what is worth spending time on. Since the space opera portion demands excitement, we should dedicate time to action, for certain. The gothic part is about reactions to horrific encounters, so we will need to give characters time to react to moments of the grotesque. The latter may occur during the action, so the narrator should be prepared to pause the action to let people soak in the horror before pounding forward. This will be our version of a James Bond villain pausing to explain his nefarious plan. During these pauses, everyone seems to forget that the laser beams are flying and gets to react. We can minimize time spent on mundanities like training or shopping; that just happens off-screen or in a montage.Plot

Plots are basically planned strings of events linked by a causality about which a story is told. How stuffy. The plot is what happens in a story. Both space operas and gothic novels have a pretty traditional plot structure, but largely due to the time in which they were predominantly created, gothic novels give more space to exposition and dénouement than space opera tends to. We should also consider how we want to spend our storytelling time, i.e. pacing. There needs to be time to introduce the basic plot during some sort of exposition, but the main point of a gothic space opera is the action that brings characters into contact with the horrific, and their reactions to those horrors. This suggests a minimization of expositional devices like finding the adventure and preparing for it. Of course, any of these could be a mini-adventure in itself. What it really boils down to is that we need to get the ball rolling quickly. Similarly, once the climax is over, the characters don’t need to spend hours dealing with the fallout. Some time should be allotted to enjoy the aftermath of their brush with horror, but their reactions are the point, not selling loot, lying in a hospital bed, or attending funerals. So wrapping up the story should be done quickly and with a degree of finality so everyone knows it is over.Setting

Setting includes both the time and the location of the story. Since the entire point of this series is to build a setting, we won’t go into too much detail here. Instead, let’s consider common inclusions in a gothic setting and in a space opera setting. Tackling the former first, gothic stories are typically set against a backdrop of either pure beauty or, more often, one of decay. They have a surreal texture and typically include elements of the supernatural – often with religious undertones. Such stories also tend not to move around too much, and they revel in the minutia of everyday life. Space opera tends to be set against a wondrous and vast world that the story ultimately jumps and flits across. There are often elements of the supernatural, as well, but it is usually cloaked in science. They tend to dispense with daily minutia in favor of focusing on dramatic action. Our setting will likely skew toward the space opera side of things, but perhaps set in a time of upheaval. Perhaps institutions are in decay and society is descending into decadence. We can explore this sort of thing more thoroughly later. For now, we know we need a sprawling setting with some sort of supernatural elements and a feeling of decay.Style

In literature, this refers to the author’s choice of words, preferences for sentence structure, and tendencies regarding paragraph structure. As such, there is an argument to be made that dictating such things to GMs or players simply is not appropriate. After all, everyone comes from different backgrounds, speaks differently, and has different levels of vocabulary. But what we can do is make some recommendations for how diction, syntax, and structure can contribute to mood and tone. Word choice is critical when attempting to convey tone or induce a mood. For example, I could say, “the room was cold and empty”, or I could say, “the deserted chamber’s door braced against the anticipation of yet another brumal day spent awaiting the return of some forgotten inhabitant.” One of these conveys a mood, if not tone. But there is a limit to how much flowery, descriptive language is good. Use such descriptions to build tension and set a feeling. Diction like this doesn’t have a place mid-battle – that’s where clarity and pacing is paramount. Similarly, sentence and paragraph structure can be quite complex while still being grammatically correct. And anyone who has read Shakespeare knows that limits to which syntax may be stretched is quite far indeed. Again, getting fancy is for initial descriptions and where you want to control the pacing. Parsing such sentences can be taxing and time consuming for players. Overall, my advice here is to use style to effect. A master of this was Edgar Allen Poe. Consider the mood he generates with these two passages:True! –nervous –very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? – “The Tell Tale Heart" by Edgar Allen Poe

I must not only punish but punish with impunity. A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong. ¬– “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allen PoeThe former is quite clear, yet its terse and almost stuttering verbiage embodies the narrator’s nervousness and neuroticism. Anyone who has read the short story is also aware of how the narrator’s tone and speaking pattern further underscores his own madness. The latter is far less clear and easily parsed, but that draws the reader’s attention in, forcing him to spend time understanding exactly what the narrator is trying to say. And this additional time not only helps the story’s pacing, but also gives weight to the ideas contained therein – something important considering it encapsulates everything the reader will encounter as the story progresses. So in short, the GM and players alike should be vigilant in their attention to the language they use, if at all possible. Careful use of diction and syntax will craft an atmosphere to be remembered for years, and thoughtless use will tear down a mood and tone in seconds.

Theme

While any given adventure can have nearly any theme, we will discuss here themes emblematic of the setting as a whole. These themes will weave throughout the setting in a way that helps contribute to its tone and mood. We will also use these themes to set up opportunities for gothic space opera adventures. These will largely involve epic struggles within and without – after all, we need the daring of space opera and the internal struggle with one’s fear of gothic horror! Space opera often concerns itself with Good and Evil, but this is far too black and white for gothic horror. We need something a little subtler that can still operate on a grandiose scale – corruption versus purity. Here, we will see pure people in impossible situations making horrible choices that corrupt their souls. We will see people of few scruples plumbing the depths of depravity. And we will use it all to force PCs to confront their own humanity. And on the subject of humanity, let’s consider one of the biggest drivers of fear in people – alienation. People are, by their nature, social animals, but when you strip them of that social connection via distrust and paranoia, you isolate them from their instinctual support mechanism. This is the sort of thing conspiracy horror is made of, but we needn’t limit ourselves to conspiracies alone. Political intrigue, body snatching aliens, serial killers, an increasingly asocial society, etc. can all drive this theme. Extending the idea of alienation even further, we reach isolation as a theme. People in space are incredibly isolated if we treat space travel with even a shred of realism. Space is among the lease habitable environments imaginable, and it can easily take days to reach even a relatively close habitat. That means being utterly isolated from help for that entire time. Colonies are even more isolated, as are ships en route to a destination. This lets us play up the science fiction aspects while maintaining one of the strongest drivers of horror. Two other themes can help drive isolation and alienation – change and disillusionment. People living in times of rapid change often fear they will be isolated from society when those changes ultimately leave them behind. This can lead to sense of disillusionment with the tacit promises made by the society they grew up in and that is now abandoning them. These have historically combined to produce a variety of fear-driven emotions – depression, betrayal, hatred, rage, etc., and those lead to horrific acts against the perceived agents of change. Thus change and disillusionment can hang over the setting as a dark cloud that randomly sparks instances of the grotesque. I think that for now, this is sufficient to begin with. We may see that other themes emerge or that some of these are less workable in practice than I am currently anticipating. Time will tell.Tone

If mood is how the audience feels about the story, tone is how the narrator feels about the story. And let’s take a minute to remind ourselves that there are multiple narrators in a roleplaying game. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that the narrator is not the author; the players need not harbor the same feelings about the story as their narration portrays. This will require a good bit of separation on everyone’s part, but it will be worth it. So let’s get on to what tone we want for this game. Gothic literature tends to be rather pessimistic in tone. It is revolted by the world it describes and sees only ultimate demise on the horizon. This is quite the opposite of the pervasive optimism of space opera, but space opera also views the world with excitement and wonder. Because so much of what makes a gothic novel is that oppressive revulsion to the world and sense of impending doom, I do not think we can discard that in favor of optimism. However, we can mix it with excitement and wonder. Let’s define a gothic space opera’s tone as one of wonder at a world so fundamentally revolting that one cannot help be drawn in. The narrator views events and people with morbid curiosity and a desperate need for some shred of decency. This might lead to a self-imposed false naivety at times, but that’s typically when something horribly revolting shatters the façade the narrator built and drags him back into the dark reality of it all. I keep thinking of the original six Dune novels by Frank Herbert. Now that we know that, let’s look at how we accomplish this. While setting elements and character actions and reactions will play a huge role in establishing the tone, the single biggest effector will be the style used by the narrators. Word choice, descriptions, and figurative language are our friends, here. I’ve already pontificated ad nauseum on the sagacity of argute diction so I’ll adjourn before you slip into lethargic oblivion.Tying It All Together

Now that we've taken a closer look at just what a gothic space opera is, let's summarize what we've found:- Players are also narrators.

- Narration should generally use third-person or alternate between first- and third-person point of view.

- Third-person subjective voice, and omniscient voice are best suited for a gothic space opera.

- Attempting to use the past tense may well be worth the effort, but consistency in tense is more important.

- A mix of interactive narration and narratives will be supported.

- Player characters should be moderately rounded, dynamic, and individualized while NPCs should generally be flat, static, and stock.

- The setting needs to provide a beautiful, wondrous, and awe-inspiring backdrop for our stories.

- Antagonists should overwhelmingly outmatch the protagonists.

- Characters need space within the setting to act, be it legal space, physical space, etc.

- Pacing is important, and we will give temporal space to events with a lot at stake and reactions to horrific encounters.

- The setting will include some sort of supernatural aspect.

- The setting will be both sprawling and decaying.

- Diction is important but not something that will affect rules. Still, we will use diction in our descriptions to create an appropriate mood and tone.

- The setting will explore and exploit themes of alienation, isolation, disillusionment, and change to set the mood and tone and provide adventure hooks.

- Good use of style and judicious shaping of the setting and plot will set a tone of desperation, morbid curiosity, and revulsion.

Comments