Brandon Sanderson on Plotting and Foreshadowing

I should probably start this with a disclaimer that you will probably find a ton of Sanderson influence in this world because he is pretty much my writing idol. I highly recommend that you check out his lectures directly here and here, but if you do not have four and a half hours to spare, I’ve got you covered.

What is plotting?

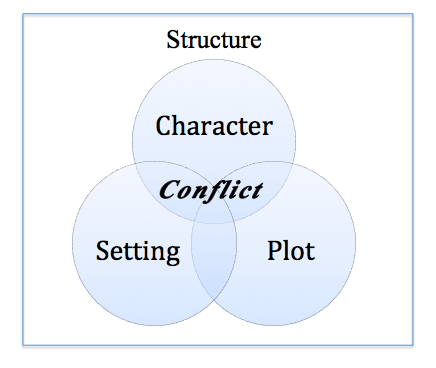

Brandon Sanderson constructs what he calls the window into novel writing. I will not go too much into it here, but I will give you a very brief overview. Within a story there are three elements – plot, character, and setting. These three components interact with what we call conflict. The window is through which we view these events is the language and prose that the writer employs to tell their story. The purpose of this us, that when you approach plotting, be aware that you need to create something that will spark that conflict between the elements and thus move the story forward.

Let’s Talk about Promises

A plot is comprised of a series of promises that are made to the reader. I for one am very discerning about the books I choose to read, and as a result can usually tell within the first chapter of the book if it is something I wish to pursue. This is exactly how the reader operates. As the author this may seem irrational or unfair, but what it all boils down to is the promises you are making. A promise is a presentation that you make to the reader about what they can expect in your book. You will be making these all the way through, but it is what you put at the beginning that is the snare that will draw readers in. The promises that are usually featured within the first third of the book are as follows:

- An interesting premise: You are making a promise to your reader, that during the book you are going to explore the ramifications and effects of the premise. It will be just as thought-provoking throughout the entire book.

- Interesting Character: You are promising your reader that the character is proactive and engaging and is going to spend the book doing awesome and interesting things.

Other things should feature here such as the introduction of supernatural elements. There is no need to tell everything, but an unforeshadowed supernatural presence can backfire as a cop-out. Promises are an excellent tool to provide your story with momentum and a sense of progression. They do not all need to be mind-bending twists, but small questions with satisfying answers are essential as well.

Foreshadowing

A common writing adage states that “The best twists are surprising, yet inevitable.” Instinctively, we shy away from this statement: If it is inevitable, how can it be that epic, mind-blowing twist I want? The answer all comes down to foreshadowing. Let me ask you a question: If we were not introduced to the mirror of Erised until the confrontation with Quirrell, would that have been a satisfying conclusion? Um, no… That is because it would seem like J. K. Rowling wrote herself into a corner and had to make something up to solve the problem. That is what foreshadowing means. We did not know that the mirror could be used in such a way that Dumbledore configured it too, but we knew enough about it that we could take a leap of faith and accept the twist: The twist was satisfying, surprising yet inevitable.

There are various ways you can go about foreshadowing. It is similar to the way you would approach a promise. Some call this “hanging a lantern” – saying “Hey, here’s this random unexplained event. It’s gonna be important later, and you’ll feel awesome for remembering it.” – alternatively, you can use a prologue, which is also fantastic in setting the tone, or by manipulating your character’s perception. The language you use is also integral. I happen to hate romance focused and explicit books (there’s nothing wrong with them, just personal taste). If a book starts describing how a girl working in a bar wears basically non-existent shorts to display her sexy legs and get more customers, then I’ll assume the book is going in a direction I don’t like and put down the book (this is not a point of prejudice against girls, or shorts, or bars, merely a real-life example of when I tried to read “The girl in The Moon”). The things you pay attention to in your writing will convey to the reader the type of book you are writing.

The actual Plotting: Generating Ideas

There are dozens of different ways to do this, and Sanderson covers various ones in his lectures, but I am just going to cover Sanderson’s method here.

Assuming you have got some ideas of setting and characters, its time to start brainstorming. If you have a vague idea of what you want to happen in your story, jot these down as headings. Headings cover everything from red herrings and major events to character arcs and relationships. Under those headings, go ahead and write down the things that need to happen for it to take place. For example, working off “Les Misérables” by Victor Hugo, under a heading such as “Jean Valjean becomes and Honest man”, you may find items such as

- Works galleys for stealing bread.

- Beaten and tried to flee.

- Rejected by townsfolk.

- Meets a generous priest and steals from him.

- Gets captured with the stolen silver, and says it was given to him.

- Priest bails him out, by not just saying this is true, but by giving him additional silver.

- Renewed faith in humanity.

You can end up with headings you do not even touch, and that is okay. Your book does not need to be so full that your reader has to dredge through chapters about the strategies employed at the battle of Waterloo to find the single event that takes up no more than a few pages, but is pivotal in the dynamic between Marias and the Thénardiers (The original books contain plenty of gems, but the recounting of Waterloo is not one of them).

The Actual Plotting: Piecing it Together

Once you have a sort of collage of ideas, it is time to begin deciding where each one should go. If you dive the book into three parts, here is a general idea of what each one should contain:

Part one:

- Promises, foreshadowing, premise.

- Engaging characters.

- Introduction of basic world elements.

- Introduction of the protagonist’s motive and opposition.

- Introduction of antagonist and their motive and goal.

Although this may sound counter-intuitive, by the end of your first third, your reader should understand what the goal is and the general ‘mission’ of the book. Bilbo knows he’s going to steal treasure from a dragon (The Hobbit, J. R. R Tolkien), Vimes knows there is prejudice against the goblins (Snuff, Terry Pratchett), Wendy knows that she is going to be a mother in Neverland (Peter Pan and Wendy, J. M. Barrie), we know that they accidentally set the spiders to evolve and burnt the monkeys (Children of Time, Adrian Tchaikovsky).

Part Two

- Earn your ending: Foreshadowing and setup of the final battle, twist, or otherwise.

- Making your ending possible and probable.

- CHANGE. Character progression and evolution.

- The illusion of progress – even f there is not a lot of action, character, and idea evolution makes it seem like there is progress.

- Red herrings (optional) and failures

However, the middle is not just merely a means to an end, it is an entity in and of itself. Every chapter must have a purpose and progression. A stagnant middle section is a death for a novel

Part Three

Ironically, this is usually the shortest, but most satisfying section.

- Resolution of all the unfulfilled promises.

- Satisfying endings to foreshadowing.

Interestingly, satisfying does not mean a positive and happy conclusion. It merely means that it makes at least extrapolatory sense and holds up to the expectations you have built up. A great example can be found in the last scenes of Hamlet when everyone, in true Shakespearean fashion, it either murdered or poisoned. This is not a fully optimistic ending, however, it is a satisfying conclusion to the tension that has been building between Hamlet and Laertes, Hamlet and Claudius, and to Gertrude’s twisted character.

After the Plot

This method of plotting is not the most structured methods. While this is great for some, you may still be at a loss at where to even begin. I tend to use this method in conjunction with Ralph Imogen’s

snowflake method. There is no wrong or right way to go about plotting, I only endeavor to give some advice and share my research with you. Hopefully, I will cover other methods in the future.

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Comments