Inqoan

Children of Aequin

I stumbled across something remarkable today: A band of explorers encamped at the far end of the peninsula. They speak a tongue I've never heard. And they have a frightful look like no people I've ever seen before. But they were intent to keep to themselves and they seem rather harmless.

Ayden Amara, Diasporan scout, 709 AoE

I

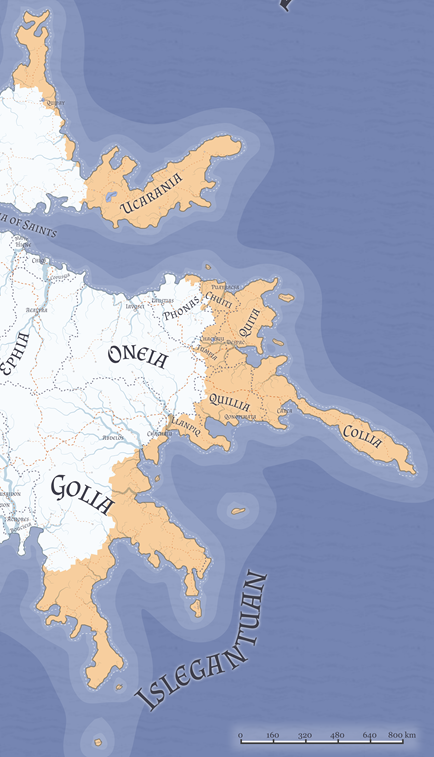

nqoans are an ethnic group found primarily on the eastern shores of Islegantuan. They are known for their distinct appearance, their close ties to the ocean, and their steadfast insistence that they are not actually casterways.

Appearance

"Full-blooded" Inqoans have grey, mottled skin. It sometimes has a blue-or-green tint, but it always appears light grey from a distance. Their eyes are "milky" or "hazy" with scant visual definition around the iris. This cloudiness can be grey, blue, or green. Their hair is typically straight, stringy, and black, grey, or deep blue. Nearly a third of Inqoans have webbed fingers. A third have webbed toes. One-in-nine have webbed fingers and webbed toes.

Diving

One of their most remarkable physical traits is their ability to hold their breath and stay submerged for periods that would easily drown any other casterway. Most Inqoans can easily stay underwater for an hour. If they conserve motion, some claim to be able to go two hours without surfacing for air. But the claims of extreme outliers are often dogged by myth, legend, braggadocio, and outright lies. This incredible ability has enabled large-scale Inqoan industries of human divers who scour all manner of valuables from deep under Aequin's waves.

Human

The extreme set of physical Inqoan peculiarities occasionally leads xenophobes to declare that the Inqoan are not actually human at all. But extensive cognoscenti documentation has shown, time and time again, that pairings between Inqoans and other casterways can-and-do happen. And when these unions are consummated, they indeed produce viable children. So despite the spectacular nature of some Inqoan traits, there is little doubt that they are still a race of humans, and not a unique species in their own right.

Naming Traditions

Feminine names

Marniam, Harvati, Masanyu, Shurya, Mayna

Masculine names

Onar, Haren, Zamayl, Unmar, Aleas

Unisex names

Nawani, Sarin, Sylasa, Farzaya, Arva

Family names

Sinqi, Amoer, Mulian, Warsif, Adnin

Culture

Major language groups and dialects

The Inqoan have no need to speak in secret codes or to manufacture elaborate cyphers. They have Qoanesh.

Bernal Cordain, Taisinian cognoscenti, 2465 AoR

Q

oanesh is the default tongue in all Inqoan regions. It is altogether distinct from any other casterway language. Most non-Inqoans find Qoanesh to be utterly baffling. The sounds are quite challenging for non-Inqoan speakers. The grammatical rules are extremely complex and greatly influenced by the context of the speakers, their shared (or not) backgrounds, and even the broader region in which they are conversing. There has never been a verified instance of a casterway, arriving directly via excilation, who natively spoke Qoanesh upon arrival. There are some cognoscenti who claim to have found faint correlations between Qoanesh and Nokmeni. This is hotly contested inside their community, with skeptics stating that these so-called "correlations" are in the eye of the beholder, caused by eager scholars who are so keen to link both languages that they will eventually find any specious likeness to validate their theory.

Commitment to Qoanesh

Inqoan regions tend to be very insular and exclusive with regard to language. Although most Inqoans can speak some Komon if forced to do so, the language is never used casually between fellow Inqoans. Very few ever bother to learn other languages outside of Komon and their native tongue. Their signage and official documents are rarely written in anything other than Qoanesh. And they are not shy about expressing their disgust if they ever think they are being compelled to step outside their lingual comfort zone.

Culture and cultural heritage

T

he common thread of all Inqoan culture is the sea - and more specifically, the Aequin Ocean. So much of the Inqoan's cultural identity is tied directly to the sea. Their cuisine, their chosen professions, their houses and structures, their myths and legends - it all makes constant references to the sea. This simple fact has defined traditional Inqoan lands as being specifically coastal. They have never made any serious attempt to colonize (or conquer) lands that are too far from the ocean. They can get along comfortably in freshwater (river) regions, but most of them prefer to have easy access to saltwater. With their incredible abilities to operate for long periods underwater, they're known to simply walk into the sea, swim to a nearby point on the ocean floor, and just sit there, in aquatic stillness, as they meditate over life.

Common Dress code

I

nqoans are quite sensitive to direct sunlight and greatly dislike open exposure. With this in mind, much of their fashion tends to reflect this reality. They gravitate toward wispy garments and shrouds that flow over them in layers. Men and women frequently use some kind of veil or face covering, but they don't care at all for traditional masks - because they seem irritated by rigid materials held firmly against their skin. There's little evidence that Inqoans are more susceptible to sunburns. They just don't enjoy being under direct sunlight and they often have some kind of sheer covering over their whole body, even in hot and humid climates. It's very common for adults - and especially, the elderly - to choose colors that outsiders would call "drab". This includes blacks, greys, and deep shades of blue, green, or purple. More colorful attire is viewed as a sign of youth (and immaturity). There are, of course, some Inqoans who don't conform to these norms, but most see dark hues as a signal of responsibility and social conformity.

Art & Architecture

G

iven their long history, they can certainly claim a full docket of artistic works in all media. Some works are even renowned well outside Inqoan lands. But the art form most associated with Inqoans is dance. Most Inqoan festivals feature extensively-choreographed performances. They can be executed in small groups, but large-scale choreography is a common characteristic of their public celebrations and rituals. It's customary for city-wide celebrations to include coordinated presentations deploying dozens - or even, hundreds - of dancers all operating with impressive synchronicity. Traditional Inqoan dance is renowned for its athletic nature. It liberally borrows elements of gymnastics, coupled with feats of strength and daring, and accentuated by elaborate costumes. These epic displays can last for hours on end.

The festival was a rhythmic soup of arms and drums and legs and drums and somersaults followed by ever more drums. When the vintage overtook me and my senses could process no more, I stumbled off to a quiet corner where I could rest and doze off for a few. I awoke, several hours later, and they were still dancing. With no visible signs of stopping any time soon.

Marna Froehn, Masalian diplomat, 1747 AoE

Music

Traditional Inqoan dance is accompanied by their own unique style of music. It's characterized by constant, droning drums that repeatedly return to thematic rhythms. Those rhythms are then offset with a host of "exotic" sounds reminiscent of Excilior's natural wildlife - birds chirping, predators growling, etc. Casterway accounts of these galas continually return to a common word to describe the effect: hypnotic. Some observers report feeling as though they spent extensive time in a trance-like state, even when they've consumed no intoxicants and they've only been observing the events for minutes.

Inqoan love of dance is not limited to formal, choreographed displays. Nearly any Inqoan celebration will have liberal time set aside for all attendees to dance. Even a simple get together, including only a small group of good friends meant to commemorate no incredible event, can still conclude with all participants dancing. For hours.

Verse

Although they have a long and varied literary tradition, their most prolific works take the form of verse. The oldest Inqoan sagas were originally written to be chanted, with a larger group of readers repeating the underlying canto, while a primary speaker voices the main narrative over the top of the chant. In more modern works, they are known to experiment with all manner of poetry, from free-form verse to tightly-structured sonatas. They are so accustomed to verse that they see it as a "normal" means of writing - with many official government policies and documents being codified in poetic structures. It even works its way into their ad hoc conversations. Foreign observers hvae noted the seamless frequency with which Inqoans will often form conversations consisting partly or entirely of ad hoc verse.

Architecture

Inqoan architecture is notable for the extent to which their buildings often extend into the water. Sometimes this takes the form of rooms supported-and-raised via stilts. But many Inqoan buildings also feature chambers that extend directly into the river or the open sea. This serves them well in those times when they simply choose to walk directly to the sea/river bottom.

Common Customs, traditions and rituals

M

ost Inqoans boast an impressive arsenal of finely-pointed teeth. This is not a genetic trait. As soon as children have received all of their adult teeth, the chiseling process commences. It's a gradual transition that is done slowly over years. But most have finished the chiseling process somewhere around the age of 25. The number of teeth that get chiseled varies based on local customs and individual tastes. Some go so far as to have all 32 teeth chiseled into exquisite daggers. But most settle for only an assortment of teeth at the front of their mouth. With evolving fashion trends, some generations have experimented with different shapes. But the simple, sharp, pointed result is still the most common objective when adolescents begin the chiseling process. The chiseling process obviously removes a good part of the protective enamel and many Inqoans have severe tooth decay in their later years, largely depending on how aggressive they were when chiseling their teeth as youths.

When it was time for the main course they wheeled a procession of barrels into the banquet hall, each containing a portion of seawater with a teeming slurry of live fish and crustaceans. With murderous abandon, every Inqoan spent the better part of the next hour reaching into the barrels, extracting a squirming creature, and tearing into the live flesh with their dagger-like teeth. The air was thick with slurping, cracking, and other sounds of active oral butchery. I thought Holoran was going to faint. Abelin completely lost his appetite. And I could bring myself to do nothing but stare at the carnage, speechless, with mouth agape.

Anelia Alberro, Argosian merchant, 3144 AoG

Cuisine

To uninitiated outsiders, cuisine is one of the most notable (and alarming) aspects of Inqoan culture. Most Inqoans prefer a diet that is almost entirely based on the sea (or on rivers). They have a deep love of fish, but they'll gladly eat crustaceans, mollusks, or nearly any other thing that was dragged from the water. They will occasionally dine on seaweed or other water-based vegetation, but this only makes up a small portion of their diet and they abhor most land-based fruits and vegetables. But casterways are not typically shocked by what the Inqoans eat so much as how they eat it.

Devouring the Living

Nearly all Inqoan seafood consumption entails grasping a living creature and tearing into it while it's still wriggling/squirming/snapping/etc. Inqoans will, at times, settle for seafood that has been previously butchered and is still raw. But they frown upon this and will do everything possible to ensure that they have access to the "freshest" (read: live) fish available. They will only eat cooked seafood if facing starvation. By Inqoan culinary traditions, cooking fish (or nearly anything else, for that matter) is tantamount to destroying it. Some Inqoans will wax lovingly about the subtle cornucopia of exquisite flavors that can only be tasted and appreciated when consuming a creature while still alive. They are also incredibly "efficient" eaters. Inqoans typically consume the entire creature - bones, entrails, eyeballs, carapaces... everything. This isn't always feasible. Depending upon the species being consumed, some bones or shells are just too large or too hard to be crunched and swallowed. But what they can manage to break up, chew, or puncture is well known to leave foreigners astonished (and aghast).

Funerary and Memorial customs

T

raditional Inqoan funerals have always taken place in the Aequin Ocean. When Inqoans die away from the Aequin, and there are none of their kin around to prepare their body and take them out to sea, this is viewed as a general tragedy. To most Inqoans, having their bodies buried, in a traditional sense, or otherwise trapped on land (e.g., on a battlefield) is equivalent to being "lost" for all eternity. Many of their ghost stories involve those who died on land and were never returned to Aequin for a proper funeral - resulting in a tortured spirit that roams the land and wreaks terror upon the muddfoots.

Consumed by Aequin

When proper funeral rites are available, their friends and family crowd about large skiffs that transport everyone to the chosen funeral site. Specifically, Inqoans have preferred locations where they know the waters are rife with carnivorous, scavenging sea creatures. Before the deceased is returned to the sea, they seed the immediate area with chum, whipping the underlying scavengers into a feeding frenzy. Once the body is dropped into the Aequin, the surface waters immediately begin to roil as the departed is quickly consumed. Assuming that a sufficient volume of scavengers has been baited into the immediate area, it's assumed that almost none of the dead body will ever reach the seafloor. In Inqoan cultural teachings, this is the highest form of funeral, characterized as being consumed by Aequin herself.

Common Myths and Legends

T

he most widely-known, and oft-repeated, Inqoan legend is that of their first appearance and establishment in eastern Islegantuan. According to Inqoan mythology, Mayara Shunrin, aboard an exploratory vessel containing 72 Inqoans, landed on the easternmost point of the Collian peninsula in 708 AoE. This may not be extraordinary in its own right, for there were numerous groups of casterway settlers trying to find new lands and establish their own independent colonies at this time. But the Inqoan account contains several details that border on fantastic and are still, to this day, debated by the cognoscenti.

Female Settlers

Mayara's settlers comprised a curious mix of genders. Of the 72 people onboard, 62 of them were female and all were of childbearing age. This would be an unusual exploration party in any environment, but it is especially notable given that Inqoan reproduction is constrained by the Plague of Men, just as it is for all other known humans on the planet. The fact that they landed with such an overwhelming proportion of women indicates that they were keenly focused on colonizing land and expanding their culture as fast as possible, despite the Plague and the extreme challenges that it often presents to new colonies trying to establish a foothold.

We were here before Aequin had any knowledge of the casterways and we'll be here when Aequin has lost all memory of the casterways.

Kalina Slynova, Quillian elder, 3754 AoG

Not Casterways?

Since their first mention in the cognoscenti archives, the Inqoan have always steadfastly maintained that they are not casterways. They claim to have no history of excilation and they have always seen themselves as an entirely unique race of humans - distinct from any others found across Excilior. There is certainly anecdotal evidence to support this. Their appearance, and their physiological peculiarities, are undoubtedly unique amongst all casterway cultures. And their language - Qoanesh - seems to have no roots or similarities in any of the other casterway tongues. In fact, Qoanesh employs a distinct set of phonemes that most casterways find nearly impossible to replicate at all.

However, there have only ever been two accepted, verified means by which humans have reached Excilior. Cervia Polonosa is known to have crashed on the planet, off the west coast of Islemanoton, and her arrival is generally acknowledged as the spark that eventually launched all casterway cultures. Every other human is presumed to ultimately trace their lineage back to some man, at some point in the near-or-distant past, who fell into the Dropship Seia, encased in a dropship.

Inqoans reject this notion. They adamantly deny that any of their ancestors ever endured excilation. Furthermore, they insist that their lineage is far older than the known history of casterways. The cognoscenti cheekily acknowledge that they cannot disprove such claims. But they also point out that there is not a single shred of evidence to explicitly prove such stories. While the cognoscenti are justified in their skepticism, even they will admit that there has never been a single documented case of any casterway arriving via dropship who features the particular set of traits that are unique to the Inqoan race.

From the East

Starting with Mayara's original landing party, Inqoans have always held that her band of settlers came "from the east". Some theories surmise that this means they actually originated from the western shores of Isleprimoton, and that Mayara's exploratory vessel managed to circumnavigate the planet, sailing west from Isleprimoton until they actually landed on the eastern extreme of Islegantuan. This explanation is, at least theoretically, feasible, although it's also considered extremely implausible. Even with the latest nautical technologies, there has never been a proven, verified instance of any casterway accomplishing this feat. And Mayara's vessel is known to have been far more primitive than those available to modern saltfoots. Skepticism is furthered by the fact that there no records from this time of anyone in western Isleprimoton having Inqoan traits. So if her "people" were already established in Isleprimoton, there is no longer any record of them whatsoever, and no one can even say exactly where in Isleprimoton they might have been based.

Of course, if the Inqoan claims are true, it would imply that, somewhere on Excilior, there is (at least) one additional landmass that is home to their ancestors. This would also mean that there is (or was) an entire civilization of humans on the planet that has nothing to do with casterways, excilation, dropships, or the Absents. Most cognoscenti dismiss this notion as simply being far too improbable and completely unsupported by any empirical evidence. Skeptics also point to the fact that the Inqoan's own histories give absolutely no detail whatsoever about the society, culture, or location of Mayara's people. While the Inqoans are adamant about their supposedly-ancient history, they have absolutely no record of that history at all. All of their teachings and all of their archives literally start from the day that Mayara's band of settlers arrived on the Collian peninsula - as though all of natural history began from this specific point.

Historical figures

E

arly Inqoan history is dominated by Mayara Shunrin. She is the founder and matriarch of the entire Inqoan culture. Although Inqoans can boast many luminary figures throughout history, her visage continues to loom large in the essence of what it means to be Inqoan. She established the first beachhead on the Collian peninsula with her proto-colony of settlers. She laid the groundwork for what became the formal nation of Collia. Her teachings and writings served as the basis for the Inqoan Expansion, which established a permanent foundation for her people and sentenced an entire culture - the Diasporans - to a permanent existence as rogues and wanderers.

Ideals

Gender Ideals

There is no force of nature more terrifying than an Inqoan woman. There is no accident of nature more useless than an Inqoan man.

Marten Robaine, King of Chevia, 2162 AoR

I

nqoan societies are almost always matriarchal. Women hold most of the powerful positions in government and religion. Although they are subject to the Plague of Men's constraints - just like everyone else on the planet - the Inqoan ideal of motherhood and child raising is that children simply mirror their mothers, at nearly all times. This means that an Inqoan woman, in the midst of any "official" duties, might still have half a dozen children in her immediate vicinity at all times. Across Inqoan culture, there is little distinction between activities that are appropriate for children to attend and activities that are not. If a woman is expected to be present, then it's usually assumed that her children will be somewhere around her throughout the process. And since it's usually the women who are in charge, this means its a given that their children will be tolerated - or even, accepted - as they conduct all of their business and attend to any official functions.

Major organizations

I

nqoans have long been associated with the Scarlet Bottonfly Company. Although it would be erroneous (and overly simplistic) to define the Company as an explicitly Inqoan organization, there is no debate that the group's leadership has always been exclusively Inqoan, or dominated by those of Inqoan descent. This ethnic influence has also led many to characterize the criminal underworld struggles between the Reaper Syndicate and the Company as a conflict of Elladorans versus Inqoans. But again, painting the struggle in this light is to brush over deeper, more-nuanced distinctions between the two syndicates.

Comments