The Scarred King I: Exile ~ Chapter One

by Josh Foreman

by Josh Foreman

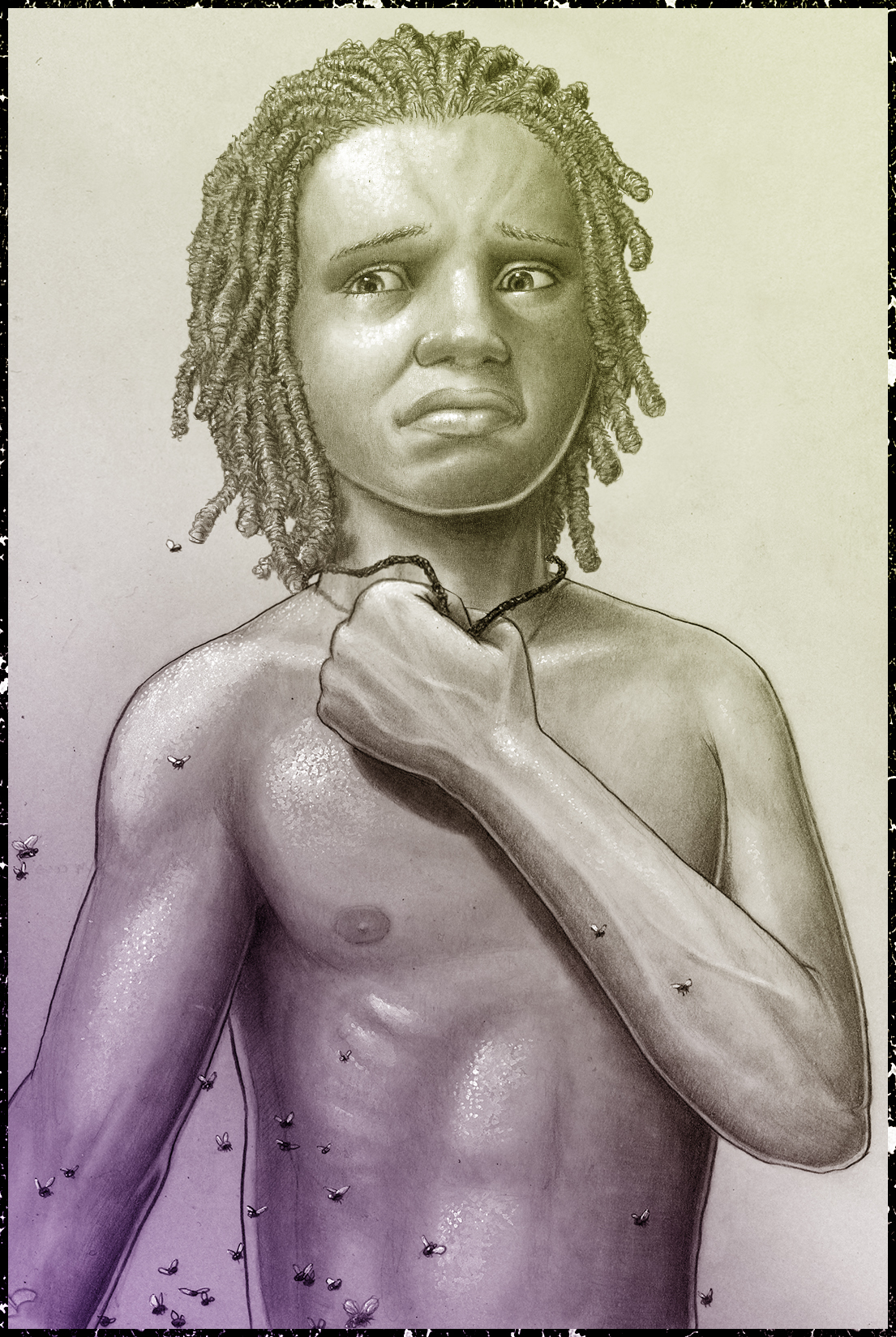

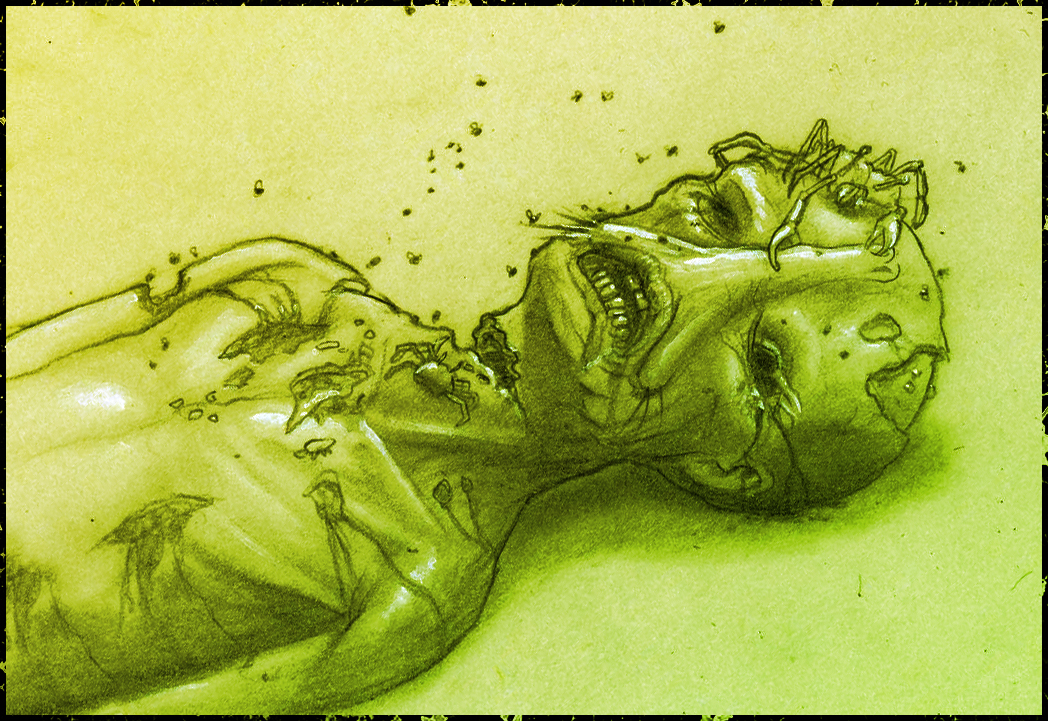

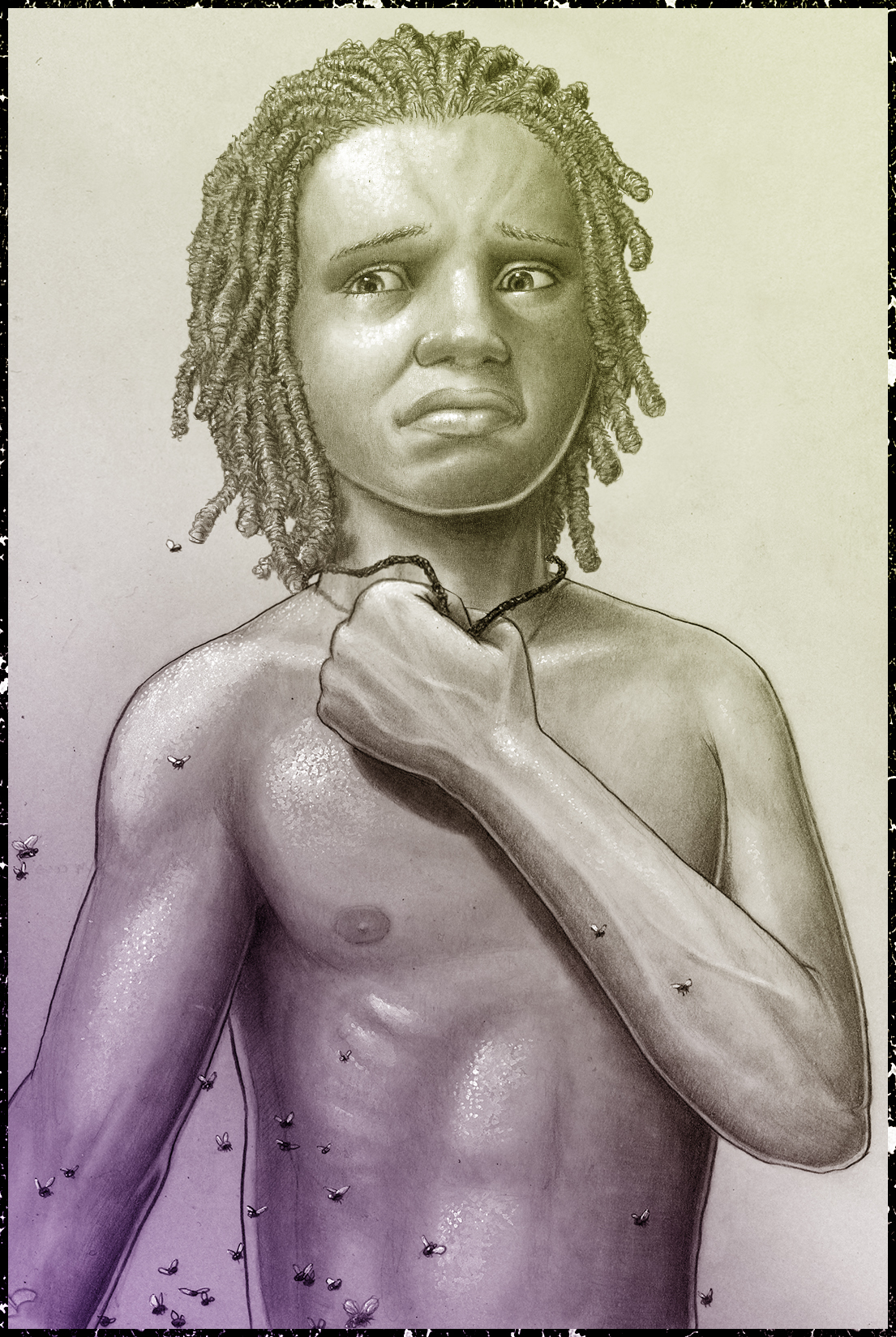

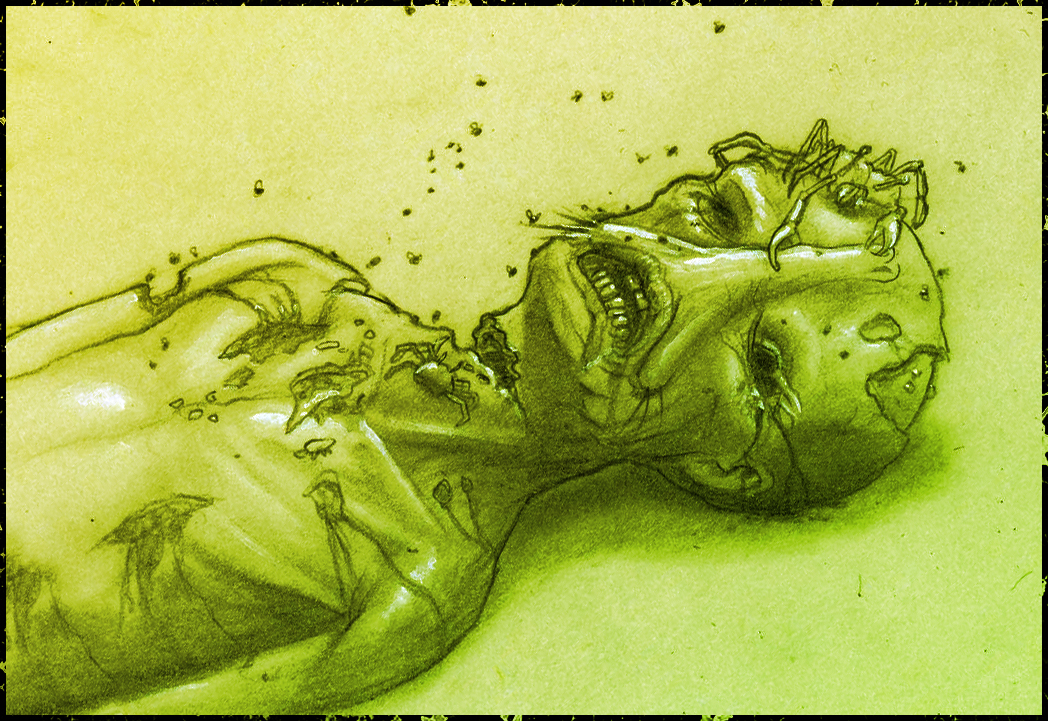

Ten-year-old Bowmark stared at two lifeless bodies on the beach: their skin ashen and gray, their fingers and toes long and webbed, the place on their faces where they should have had noses, flat and smooth. They must be adolescents older than him. And what were the small slits like porpoise’s nostrils gaping on their foreheads?

He could not tear his gaze away from where the crabs and gulls ate at their eyes and picked pieces off their faces. Revolted, Bowmark waved them away until the scavengers retreated beyond Father and his entourage.

The local fishermen had likely contributed to the damage with their scaling knives based on the long gaping wounds. The crust of black sand stuck to parts of their bodies indicated a struggle; one that he tried not to imagine.

Flies rose and fell in haphazard clouds. He held his breath to avoid inhaling any.

Bowmark’s breakfast threatened to rise. He must not vomit. The king’s son must not show weakness, not in front of the forty villagers, not in front of the servants and nobles that came to investigate, and definitely not in front of Father.

He glanced at Father who was examining a gray man half out of the surf. The body had been decapitated. Father’s lips tightened to a thin line. He was famous for being inscrutable, but Bowmark could read this easily. His throat tightened. Father was furious. At me? Bowmark clutched his Giver’s Hand medallion. What should he do? He stood, his feet rooted to the black sand as the smell of decay combined with the buzzing of the flies to make his stomach hurt.

The physician RunsFast moved forward and knelt by the strange people. She inspected closely but did not touch. “My King, these might be the children of the beheaded man. I guess their ages to be thirteen and fifteen. They were stabbed to death, as he was. They did not drown.”

The surf gently touched Father’s heels, as if timid about approaching the king. Overhead, gulls screamed at the people who had stolen their meal.

Bowmark’s breakfast threatened to rise. He must not vomit. The king’s son must not show weakness, not in front of the forty villagers, not in front of the servants and nobles that came to investigate, and definitely not in front of Father.

He glanced at Father who was examining a gray man half out of the surf. The body had been decapitated. Father’s lips tightened to a thin line. He was famous for being inscrutable, but Bowmark could read this easily. His throat tightened. Father was furious. At me? Bowmark clutched his Giver’s Hand medallion. What should he do? He stood, his feet rooted to the black sand as the smell of decay combined with the buzzing of the flies to make his stomach hurt.

The physician RunsFast moved forward and knelt by the strange people. She inspected closely but did not touch. “My King, these might be the children of the beheaded man. I guess their ages to be thirteen and fifteen. They were stabbed to death, as he was. They did not drown.”

The surf gently touched Father’s heels, as if timid about approaching the king. Overhead, gulls screamed at the people who had stolen their meal.

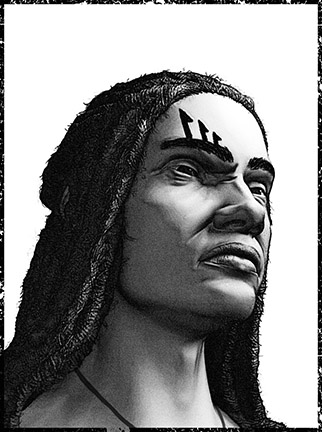

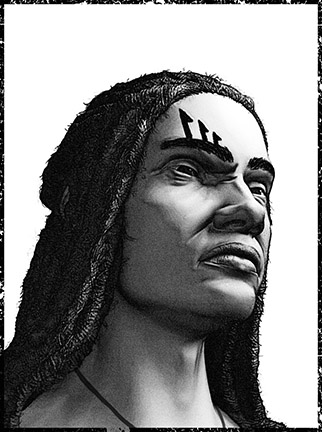

Father left the adult body and strode closer to the dead adolescents. The sea had darkened the bottom hand-width of his long, official, indigo skirt. White triangular-shell designs stood out starkly on the fabric. The steel Giver’s Hand medallion on his chest glinted in the early sunlight and the opal embedded on the palm cast a small round rainbow on the sheened copper skin of his forearm. He pulled back his tightly-coiled red hair and slipped off the loose hair tie.

WalkForward, a servant with the golden skin, golden-brown eyes, and straight black hair shared by the commoners, darted from the crowd of attendants waiting at the waterline by the canoes. He reached to redo the hair tie, but Father waved him away and redid the tie himself. The servant plucked at his knee-length brown skirt and briefly touched his wooden Giver’s Hand medallion as he backed away a few steps into the surf.

Bowmark’s curiosity overcame his revulsion and he stepped closer to these odd people. The corpses, a boy and a girl, had a bit of hair after all: tiny coarse tufts at the corners of their mouths. Both nobles and commoners of Bowmark’s people had smooth skin and no body hair except on their scalps and eyebrows. He touched the corner of his mouth.

Father left the adult body and strode closer to the dead adolescents. The sea had darkened the bottom hand-width of his long, official, indigo skirt. White triangular-shell designs stood out starkly on the fabric. The steel Giver’s Hand medallion on his chest glinted in the early sunlight and the opal embedded on the palm cast a small round rainbow on the sheened copper skin of his forearm. He pulled back his tightly-coiled red hair and slipped off the loose hair tie.

WalkForward, a servant with the golden skin, golden-brown eyes, and straight black hair shared by the commoners, darted from the crowd of attendants waiting at the waterline by the canoes. He reached to redo the hair tie, but Father waved him away and redid the tie himself. The servant plucked at his knee-length brown skirt and briefly touched his wooden Giver’s Hand medallion as he backed away a few steps into the surf.

Bowmark’s curiosity overcame his revulsion and he stepped closer to these odd people. The corpses, a boy and a girl, had a bit of hair after all: tiny coarse tufts at the corners of their mouths. Both nobles and commoners of Bowmark’s people had smooth skin and no body hair except on their scalps and eyebrows. He touched the corner of his mouth.

Then he stretched out his fingers and compared them to that of the adolescents. Since their fingers were curled, he could not see if they had fingernails like his. Their skin did not have the sheen his did. They were barely taller than him, but then, even at age ten, he was taller than most children and even some thirteen-year-olds.

One of the children he was glad to be taller than, his second cousin RaiseHim, walked up to the dead youth with a crooked stick in his hands and poked the boy.

Father surged forward, grabbed RaiseHim by the shoulder, and shoved him into the surf. Everyone stared at them.

The boy’s father, the tax collector murmured “Grant me pardon.” and waded into the surf. He slapped his son on the head several times.

Bowmark looked away from RaiseHim’s scowl. RaiseHim did not get along with his father or with Bowmark. So far as Bowmark knew, RaiseHim did not get along with anybody. He hoped RaiseHim’s canoe would trail behind so he would not need to listen to the two of them argue. They would not fight here, not in front of the villagers, but once they were at sea, RaiseHim and his father would lose control. RaiseHim would yell until his father hit him.

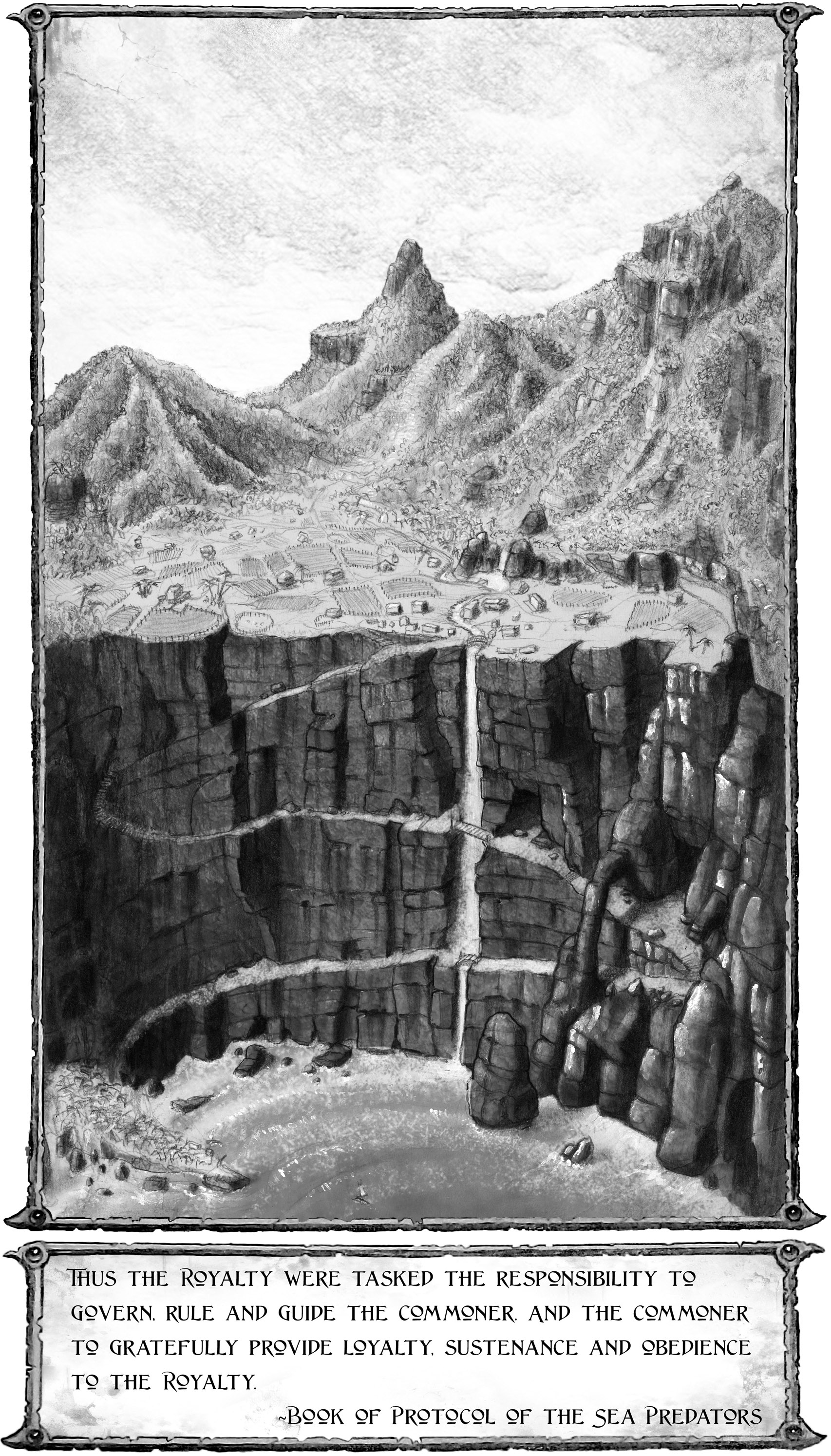

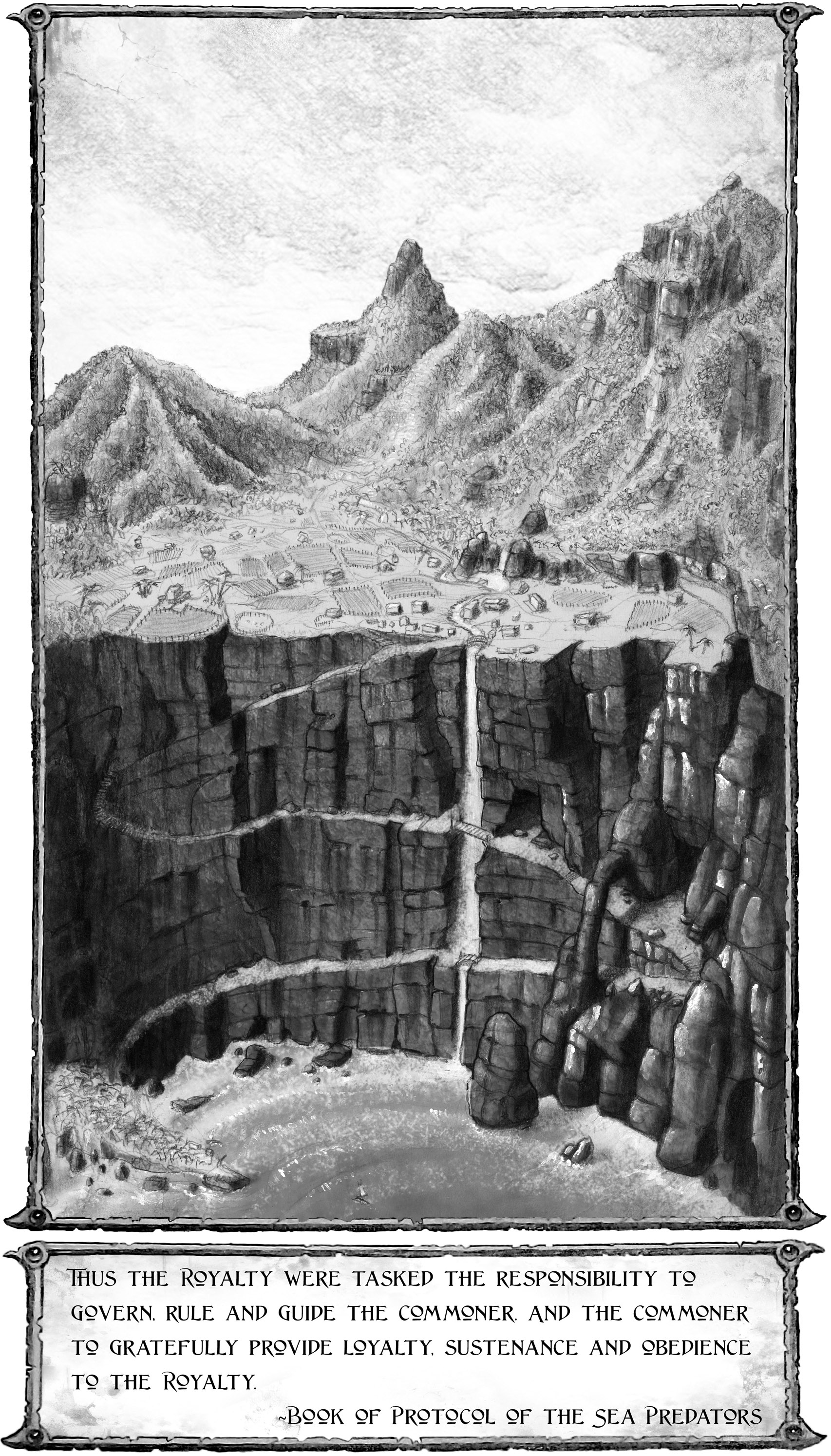

Rather than watch the predictable drama, Bowmark examined the small village. Bamboo houses perched on volcanic cliffs above the narrow beach littered with fishing canoes, nets, and at the farthest end, racks of drying fish. The fish dripped oils on the dried seaweed and rice-straw fires beneath them. The fish oils sizzled, flamed, and transformed into drifting black smoke that wandered away from the nobles.

The villagers, commoners all, stood around the fish racks with furrowed faces and studied the nobles and servants who had interrupted the judgment circuit to sail in and investigate the invasion. The surf drowned out their whispers.

Bowmark tried to direct his attention to the dead youths’ toes, but his gaze, against his will, kept returning to their ravaged heads. He swallowed again, closed his eyes, and turned away. Nobles and attendants moved around him.

When he opened his eyes, he finally saw the gray man’s head spiked on an upright paddle barely an arm’s length away.

He ran to the surf and vomited.

The maid ThreadTangle rushed to him, dipped a cloth in the ocean, and wiped his face and mouth. A strong desire for Mother washed over him. She had stayed behind at the Bamboo Palace when Father and he had sailed to WetSide.

Embarrassed, he waved ThreadTangle away. He hoped he looked as unconcerned as Father when he dismissed her, even if he had just vomited and shamed himself in front of everyone.

To avoid the eyes of the retinue, he turned away to study the islands in view. Far on the horizon rose the island of StoneShell, the largest in StoneGrove, where Bowmark’s family resided. To the north of StoneShell stood King’s Island, bristling with the Royal Forest and upon which a live volcano issued a thin stream of smoke. Smoke might mean lava was flowing.

ThreadTangle looked over where Bowmark’s gaze was fixed. She whispered, “Don’t worry. If it erupts today or tomorrow, you’re still too young. They won’t hold a proving.”

Proving. Tears overflowed Bowmark’s eyes. He vomited again. The maid cleaned him again, moisture welling in her own golden-brown eyes.

Bowmark stared at his feet. He had showed weakness, showed the fear he was not allowed to have.

RaiseHim splashed up to him and whispered in his ear, “You’re a little girl,” before the tax collector pulled his son to their canoe.

Bowmark swallowed bile. RaiseHim wasn’t afraid. He didn’t tremble every time the volcano prepared to erupt and open the time of proving. He wasn’t the presumed who was destined to walk onto the Disc.

ThreadTangle bent over to murmur, “Compassion for these strangers—whatever they are—is not bad.” The soothing aroma of coconut oil in her hair drifted by Bowmark’s nose. He rubbed his eyes. If only he could be as bold as his hateful cousin.

The protocol officer limped up to Father. The woman’s red hair had faded to a gray that matched her eyes. Her brown, spotted skin had more wrinkles than the mountains surrounding them. She also wore the long light skirt instead of the knee-length heavy skirts everyone else wore. Swinging her hand in a broad gesture that included the villagers, she leaned in close. “My King, these villagers should be rewarded for killing the enemy.”

Father pointed to the adolescents with his elbow. “These people are not our enemy.”

The protocol officer sidled in closer. “If they had lived, they might have carried word of us to our—”

“No.”

Enemy. The people that plagued Bowmark’s nightmares. The people that caused Father to spar every morning. The reason fishermen were not allowed past the islands of StoneGrove, but must fish between the islands lest they be captured and tortured into revealing the location of the last of the Bowmark’s people, the Sea Predators. The enemy tribe, the Southils, liked to skin people alive, especially Sea Predators.

Every time Bowmark asked what the Southils looked like, he was told only that they wore three line tattoos under one eye. He had not been told there existed people with gray skin and noses on their foreheads.

Turning away from the Protocol officer, Father raised his voice, “Bring three of the extra sails and their lines.”

Three of the manservants broke away from the crowd, racing to the closest end of the beach where the outrigger canoes had been pulled up under the shade of coconut palms.

A black seadog tied to the prow of the smallest canoe lunged to the end of its rope. The quills along its back rose and fell as it bugled.

The servants filled their arms with canvas and raced back to lay the sails at Father’s feet.

“Prepare them for burial.”

The protocol officer blurted, “My King! They aren’t Sea Predators. Why would we honor them as our own?”

The servants froze, all eyes on Father. Without a word he glared at them and the slight thrust of his chin set them back into action. They laid the white sails on the black sand beside the bodies and then dragged the corpses into the centers of the canvas. The protocol officer moved as though to protest again but Father’s cold eyes fixed on her and the old woman shied back to silence.

A few villagers came forward bearing rocks, laid them beside the strangers and scurried back to the watchful line.

Bowmark stepped behind Father. Perhaps if Father didn’t see him, then he wouldn’t be angry at him for showing weakness.

The gulls screamed and flapped away. In the distance, monkeys and bigfa birds hooted as though nothing momentous had happened here.

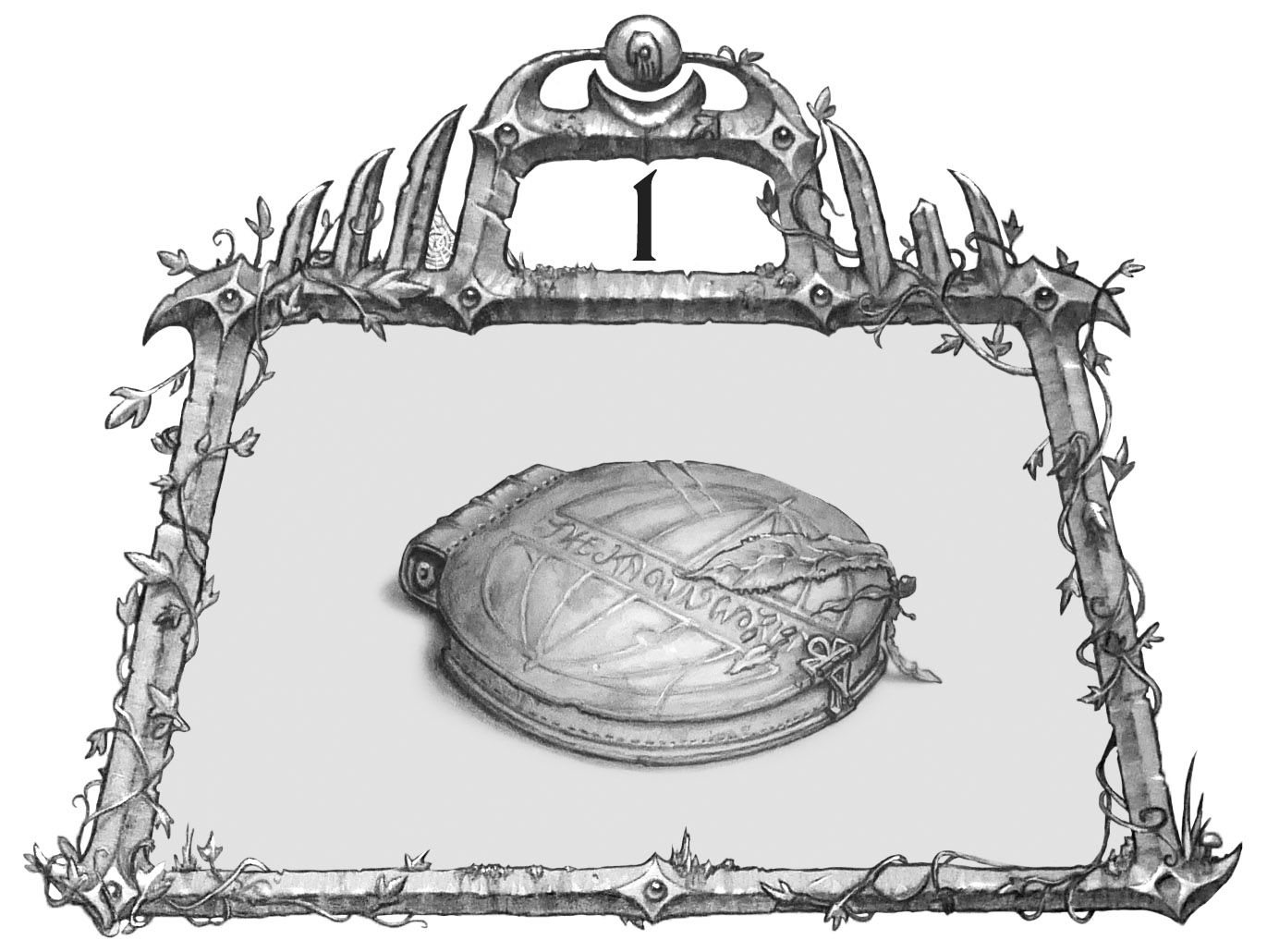

While servants wrapped and tied the bodies, the villagers around the fish racks stepped aside to let an old man through. He had gray streaks in his black hair and wore a faded brown skirt. His bare feet dented the coarse sand as he approached Father, bearing in his hands a large circular object that looked like a leather clam. The closer he got to Father, the slower he moved and the more he trembled until finally he knelt and averted his gaze as he extended the strange object. “What have we to do with books? The enemy brought this. We give it to you.”

Father took the proffered artifact, unlatched a hook, hinged it open, and turned the thick, waxed pages. The protocol officer eyed the book as though it were a snake poised to strike.

Though most of the Sea Predators learned to read at least a few words, the islands of StoneGrove had few books. The Temple held the two Holy Books. The protocol officer carried the Protocol. The Records of the Kings rested under dust in the treasury room. The language tutor consulted a dictionary with five languages. The royals kept tax records, wrote a few letters to each other, and wrote out petitions to the king on paper made of banana fiber and bamboo leaves or on thin, scraped leather from pig hides.

This strange round book was larger than the two Holy Books combined and was made of thicker paper than the Sea Predators used.

The sun cast deep shadows under the brows of the villagers as they stared at Father. He clapped the tome shut and removed a bit of seaweed clinging to the cover. “This is a book of maps.” He turned to Bowmark and thrust the book into his hands.

Bowmark gripped the volume and gulped. What was he supposed to do with this?

Father turned to his servants. “Place the strangers in my canoe.”

Some of the servants eyed each other before jumping to follow his orders. Three carried each of the bodies and laid them on the trampoline, a net-like grid of ropes strung between the spars of the outrigger to carry cargo. ThrowPebbles carried the severed head. The servants’ feet splashed in the surf.

While the servants were busy, the kingdom’s tax collector approached the huddled villagers. He would want to collect taxes on the salvage from the strangers’ shipwreck.

The only sounds were the splashing, the grind of the surf, and the squeals of ocean hawks.

Bowmark trailed behind the servants returning to the canoes. Black sand gritted under his bare feet. Sweat filmed his skin, and he squeezed the heavy book to his chest to keep it from slipping.

Although he could easily climb into a canoe by himself, SunGlare automatically lifted him. How was he going to convince them that he wasn’t a toddler, and hadn’t been a toddler for a long time, if he threw up every time he saw a dead body?

The prow of the outrigger scraped against the sand as servants shoved the red and black canoe into the surf and then splashed aboard themselves. Five more canoes followed Bowmark’s.

Men tugged on lines and the triangular, indigo sails caught the rising breeze and belled out into a tight curve. The waves sparkled in the sunlight and slapped the canoe and its outrigger as the smell of decay blew away on the clean wind.

Bowmark hugged the book against his chest and shivered, staring at the wrapped bodies. Father moved to sit beside him and laid a hand on his shoulder. Even if the question made Father angry, Bowmark needed to know. He stuttered, “W-what are they?”

Father’s deep voice held sorrow, not anger. “They are humans, as you and I are.”

A maid reaching for a calabash of water bumped Bowmark’s back. She cringed at the scowl from the protocol officer, but Father only glanced mildly at her.

Father squeezed Bowmark’s shoulder. “We Sea Predators are born with red hair or black hair. Some of us have copper skin, and some of us have golden skin. Whether we have black hair or red hair, we are all Sea Predators as well as human. In the Records of the Kings I have read about the gray-skinned humans. People who have gray skin are called seafolks. The ancestors changed the shape of many humans and animals. Humans in our age come in a variety of colors and sizes in the wider world. Every one of them has the capacity for good or evil. Just like Sea Predators, common or noble.” He looked up.

The servants who had been leaning in to listen hastily returned to their work.

Bowmark glanced back at the canoe holding RaiseHim and his father, the tax collector. They wouldn’t like Father’s words that implied the commoners were as good as nobles.

Although Father and Bowmark were pure-blooded nobles, Grandfather’s first wife had been a daughter of the first commoner to achieve royalty by proving on the Disc. After she died, he had married a red-haired noblewoman who became Bowmark’s grandmother, but the family still seemed tainted to some of the nobles.

The sailors tacked against the wind, slowing the outrigger canoe to keep on course. The flapping sail swung to a new position and its shade crossed Bowmark and Father.

Bowmark rubbed his lips with his wrist. “Are those gray people Sea Predators?”

“No. But neither are they our enemies.” Father gently tugged the book out of Bowmark’s arms and laid the tome flat on his lap. His fingers brushed the brown cover. “This is not the Sea Predator alphabet nor the Sea Predator language. You are learning Common, which is the language of the wider world. You can read this.”

Bowmark stared at the embossed strange lines and curves he could not read. He had no idea what this strange book said. This much he knew: The Sea Predators had been hiding in StoneGrove from the Southils for two hundred years. On the other side of the ocean lived Southils and other people whose names were long forgotten. People spoke Common or South there, so Father forced Bowmark to learn those languages. If his tutor had not had permission to cane him, Bowmark would not have learned any of those useless languages.

He opened the book and stared at the first and largest letters. Slowly the shapes acquired meaning. His voice quivered, “A—at. Luh. Ss. Atlas. Uh. Of. The—the. Sea. Folk. Fam—fam ih. Family. Bree. See? Breezy?” He stopped, having run out of breath. Reading was hard.

“I think the family name is Breecee.” Father squeezed Bowmark’s shoulder. “Breathe, son. You cannot think if you do not breathe.” He stroked Bowmark’s hair. “I think Atlas must be the name for a book of maps.” He pointed to the page on the right which was half filled with words in straight lines. Twisty lines filled the rest.

Father tapped the pages. “Son, I am giving you an important job. You will read this Atlas.”

Bowmark gaped. There were hundreds of pages. Considering how long he took to read the first seven words, reading the rest of the book could take years.

Father continued. “I want you to find where the Southils live. Also, we need to find out if StoneGrove is marked in here. We need to know if we have been discovered.”

Bowmark shivered at the thought of the Southils invading their islands. He gripped his Giver’s Hand medallion. His throat squeaked and he coughed to cover the sound. As the king’s son and presumed he must not be weak. He must not, or the Southils might kill them all. He swallowed, and then sniffed. “I will, Father.”

He flipped a few pages to a drawing of people in outrigger canoes with rectangular sails rather than the triangle sails of the Sea Predators. He tried to remember to breathe as he sounded out each syllable. “The Hahn of the Longboats are a fractious people, seldom willing to trade. When they are willing, they trade dried fish, fresh fruit, and coconuts for steel needles and steel pots. Father, what does fractious mean?”

Father dipped his head and whispered, “Like RaiseHim.”

They exchanged smiles. Bowmark flipped to another page with an illustration of a creature with a long tail, holding its body in the position a bird does when walking. The word under the drawing was rumsha. “What kind of animal is this?”

Father studied the page and the words on the opposite page. “This is a non-human person. There are many kinds of non-human people in the wide world. The only non-human person I’ve ever met was a shlak. Someday I would like to see a varon seacastle floating on the ocean.”

Bowmark’s brain ignited. “Do all these people want to kill us?”

“So far as I know, only the Southils and their allies want to destroy us. All the other people of the world don’t care whether we are slaughtered or left to live.”

Bowmark ran his fingers along a sentence. “I will tell you everything I learn.”

“I am pleased.” Father gazed toward still far-off StoneShell. He shouted to the servants, “Furl the sail.”

Bowmark grinned. Father was pleased! As the band around Bowmark’s throat loosened, he vowed to himself that he would read as much as he needed to find what Father wanted to know. Bowmark would protect his people.

As Father’s orders were followed, all the outriggers in the entourage slowed to drift and bob on the surface of the ocean.

Father stood and raised his hands. “May Giver grant these innocent people rest- as He deals our enemies death and destruction.” He lowered his hands. They had not brought any priests with them. Who would say the Holy Words?

“Bury them,” Father said.

Silently, sailors picked up the bodies from the trampoline and slid them into the blue water. The bundles sank rapidly, the white sail wrappings disappearing in the deep. Then one sailor muttered, “The fish feed us, then we feed the fish.”

Father settled on the thwart, the board that served as brace and seat, next to Bowmark. He stared into the distance. No one said a word, holy or not, as servants reset the sail, and the canoe plowed through the sea toward Muntee Holm, an uninhabited island, to stay the night before heading for StoneShell. Bowmark had been looking forward to exploring the tiny uninhabited islet, but now he wanted to simply go home.

Then he stretched out his fingers and compared them to that of the adolescents. Since their fingers were curled, he could not see if they had fingernails like his. Their skin did not have the sheen his did. They were barely taller than him, but then, even at age ten, he was taller than most children and even some thirteen-year-olds.

One of the children he was glad to be taller than, his second cousin RaiseHim, walked up to the dead youth with a crooked stick in his hands and poked the boy.

Father surged forward, grabbed RaiseHim by the shoulder, and shoved him into the surf. Everyone stared at them.

The boy’s father, the tax collector murmured “Grant me pardon.” and waded into the surf. He slapped his son on the head several times.

Bowmark looked away from RaiseHim’s scowl. RaiseHim did not get along with his father or with Bowmark. So far as Bowmark knew, RaiseHim did not get along with anybody. He hoped RaiseHim’s canoe would trail behind so he would not need to listen to the two of them argue. They would not fight here, not in front of the villagers, but once they were at sea, RaiseHim and his father would lose control. RaiseHim would yell until his father hit him.

Rather than watch the predictable drama, Bowmark examined the small village. Bamboo houses perched on volcanic cliffs above the narrow beach littered with fishing canoes, nets, and at the farthest end, racks of drying fish. The fish dripped oils on the dried seaweed and rice-straw fires beneath them. The fish oils sizzled, flamed, and transformed into drifting black smoke that wandered away from the nobles.

The villagers, commoners all, stood around the fish racks with furrowed faces and studied the nobles and servants who had interrupted the judgment circuit to sail in and investigate the invasion. The surf drowned out their whispers.

Bowmark tried to direct his attention to the dead youths’ toes, but his gaze, against his will, kept returning to their ravaged heads. He swallowed again, closed his eyes, and turned away. Nobles and attendants moved around him.

When he opened his eyes, he finally saw the gray man’s head spiked on an upright paddle barely an arm’s length away.

He ran to the surf and vomited.

The maid ThreadTangle rushed to him, dipped a cloth in the ocean, and wiped his face and mouth. A strong desire for Mother washed over him. She had stayed behind at the Bamboo Palace when Father and he had sailed to WetSide.

Embarrassed, he waved ThreadTangle away. He hoped he looked as unconcerned as Father when he dismissed her, even if he had just vomited and shamed himself in front of everyone.

To avoid the eyes of the retinue, he turned away to study the islands in view. Far on the horizon rose the island of StoneShell, the largest in StoneGrove, where Bowmark’s family resided. To the north of StoneShell stood King’s Island, bristling with the Royal Forest and upon which a live volcano issued a thin stream of smoke. Smoke might mean lava was flowing.

ThreadTangle looked over where Bowmark’s gaze was fixed. She whispered, “Don’t worry. If it erupts today or tomorrow, you’re still too young. They won’t hold a proving.”

Proving. Tears overflowed Bowmark’s eyes. He vomited again. The maid cleaned him again, moisture welling in her own golden-brown eyes.

Bowmark stared at his feet. He had showed weakness, showed the fear he was not allowed to have.

RaiseHim splashed up to him and whispered in his ear, “You’re a little girl,” before the tax collector pulled his son to their canoe.

Bowmark swallowed bile. RaiseHim wasn’t afraid. He didn’t tremble every time the volcano prepared to erupt and open the time of proving. He wasn’t the presumed who was destined to walk onto the Disc.

ThreadTangle bent over to murmur, “Compassion for these strangers—whatever they are—is not bad.” The soothing aroma of coconut oil in her hair drifted by Bowmark’s nose. He rubbed his eyes. If only he could be as bold as his hateful cousin.

The protocol officer limped up to Father. The woman’s red hair had faded to a gray that matched her eyes. Her brown, spotted skin had more wrinkles than the mountains surrounding them. She also wore the long light skirt instead of the knee-length heavy skirts everyone else wore. Swinging her hand in a broad gesture that included the villagers, she leaned in close. “My King, these villagers should be rewarded for killing the enemy.”

Father pointed to the adolescents with his elbow. “These people are not our enemy.”

The protocol officer sidled in closer. “If they had lived, they might have carried word of us to our—”

“No.”

Enemy. The people that plagued Bowmark’s nightmares. The people that caused Father to spar every morning. The reason fishermen were not allowed past the islands of StoneGrove, but must fish between the islands lest they be captured and tortured into revealing the location of the last of the Bowmark’s people, the Sea Predators. The enemy tribe, the Southils, liked to skin people alive, especially Sea Predators.

Every time Bowmark asked what the Southils looked like, he was told only that they wore three line tattoos under one eye. He had not been told there existed people with gray skin and noses on their foreheads.

Turning away from the Protocol officer, Father raised his voice, “Bring three of the extra sails and their lines.”

Three of the manservants broke away from the crowd, racing to the closest end of the beach where the outrigger canoes had been pulled up under the shade of coconut palms.

A black seadog tied to the prow of the smallest canoe lunged to the end of its rope. The quills along its back rose and fell as it bugled.

The servants filled their arms with canvas and raced back to lay the sails at Father’s feet.

“Prepare them for burial.”

The protocol officer blurted, “My King! They aren’t Sea Predators. Why would we honor them as our own?”

The servants froze, all eyes on Father. Without a word he glared at them and the slight thrust of his chin set them back into action. They laid the white sails on the black sand beside the bodies and then dragged the corpses into the centers of the canvas. The protocol officer moved as though to protest again but Father’s cold eyes fixed on her and the old woman shied back to silence.

A few villagers came forward bearing rocks, laid them beside the strangers and scurried back to the watchful line.

Bowmark stepped behind Father. Perhaps if Father didn’t see him, then he wouldn’t be angry at him for showing weakness.

The gulls screamed and flapped away. In the distance, monkeys and bigfa birds hooted as though nothing momentous had happened here.

While servants wrapped and tied the bodies, the villagers around the fish racks stepped aside to let an old man through. He had gray streaks in his black hair and wore a faded brown skirt. His bare feet dented the coarse sand as he approached Father, bearing in his hands a large circular object that looked like a leather clam. The closer he got to Father, the slower he moved and the more he trembled until finally he knelt and averted his gaze as he extended the strange object. “What have we to do with books? The enemy brought this. We give it to you.”

Father took the proffered artifact, unlatched a hook, hinged it open, and turned the thick, waxed pages. The protocol officer eyed the book as though it were a snake poised to strike.

Though most of the Sea Predators learned to read at least a few words, the islands of StoneGrove had few books. The Temple held the two Holy Books. The protocol officer carried the Protocol. The Records of the Kings rested under dust in the treasury room. The language tutor consulted a dictionary with five languages. The royals kept tax records, wrote a few letters to each other, and wrote out petitions to the king on paper made of banana fiber and bamboo leaves or on thin, scraped leather from pig hides.

This strange round book was larger than the two Holy Books combined and was made of thicker paper than the Sea Predators used.

The sun cast deep shadows under the brows of the villagers as they stared at Father. He clapped the tome shut and removed a bit of seaweed clinging to the cover. “This is a book of maps.” He turned to Bowmark and thrust the book into his hands.

Bowmark gripped the volume and gulped. What was he supposed to do with this?

Father turned to his servants. “Place the strangers in my canoe.”

Some of the servants eyed each other before jumping to follow his orders. Three carried each of the bodies and laid them on the trampoline, a net-like grid of ropes strung between the spars of the outrigger to carry cargo. ThrowPebbles carried the severed head. The servants’ feet splashed in the surf.

While the servants were busy, the kingdom’s tax collector approached the huddled villagers. He would want to collect taxes on the salvage from the strangers’ shipwreck.

The only sounds were the splashing, the grind of the surf, and the squeals of ocean hawks.

Bowmark trailed behind the servants returning to the canoes. Black sand gritted under his bare feet. Sweat filmed his skin, and he squeezed the heavy book to his chest to keep it from slipping.

Although he could easily climb into a canoe by himself, SunGlare automatically lifted him. How was he going to convince them that he wasn’t a toddler, and hadn’t been a toddler for a long time, if he threw up every time he saw a dead body?

The prow of the outrigger scraped against the sand as servants shoved the red and black canoe into the surf and then splashed aboard themselves. Five more canoes followed Bowmark’s.

Men tugged on lines and the triangular, indigo sails caught the rising breeze and belled out into a tight curve. The waves sparkled in the sunlight and slapped the canoe and its outrigger as the smell of decay blew away on the clean wind.

Bowmark hugged the book against his chest and shivered, staring at the wrapped bodies. Father moved to sit beside him and laid a hand on his shoulder. Even if the question made Father angry, Bowmark needed to know. He stuttered, “W-what are they?”

Father’s deep voice held sorrow, not anger. “They are humans, as you and I are.”

A maid reaching for a calabash of water bumped Bowmark’s back. She cringed at the scowl from the protocol officer, but Father only glanced mildly at her.

Father squeezed Bowmark’s shoulder. “We Sea Predators are born with red hair or black hair. Some of us have copper skin, and some of us have golden skin. Whether we have black hair or red hair, we are all Sea Predators as well as human. In the Records of the Kings I have read about the gray-skinned humans. People who have gray skin are called seafolks. The ancestors changed the shape of many humans and animals. Humans in our age come in a variety of colors and sizes in the wider world. Every one of them has the capacity for good or evil. Just like Sea Predators, common or noble.” He looked up.

The servants who had been leaning in to listen hastily returned to their work.

Bowmark glanced back at the canoe holding RaiseHim and his father, the tax collector. They wouldn’t like Father’s words that implied the commoners were as good as nobles.

Although Father and Bowmark were pure-blooded nobles, Grandfather’s first wife had been a daughter of the first commoner to achieve royalty by proving on the Disc. After she died, he had married a red-haired noblewoman who became Bowmark’s grandmother, but the family still seemed tainted to some of the nobles.

The sailors tacked against the wind, slowing the outrigger canoe to keep on course. The flapping sail swung to a new position and its shade crossed Bowmark and Father.

Bowmark rubbed his lips with his wrist. “Are those gray people Sea Predators?”

“No. But neither are they our enemies.” Father gently tugged the book out of Bowmark’s arms and laid the tome flat on his lap. His fingers brushed the brown cover. “This is not the Sea Predator alphabet nor the Sea Predator language. You are learning Common, which is the language of the wider world. You can read this.”

Bowmark stared at the embossed strange lines and curves he could not read. He had no idea what this strange book said. This much he knew: The Sea Predators had been hiding in StoneGrove from the Southils for two hundred years. On the other side of the ocean lived Southils and other people whose names were long forgotten. People spoke Common or South there, so Father forced Bowmark to learn those languages. If his tutor had not had permission to cane him, Bowmark would not have learned any of those useless languages.

He opened the book and stared at the first and largest letters. Slowly the shapes acquired meaning. His voice quivered, “A—at. Luh. Ss. Atlas. Uh. Of. The—the. Sea. Folk. Fam—fam ih. Family. Bree. See? Breezy?” He stopped, having run out of breath. Reading was hard.

“I think the family name is Breecee.” Father squeezed Bowmark’s shoulder. “Breathe, son. You cannot think if you do not breathe.” He stroked Bowmark’s hair. “I think Atlas must be the name for a book of maps.” He pointed to the page on the right which was half filled with words in straight lines. Twisty lines filled the rest.

Father tapped the pages. “Son, I am giving you an important job. You will read this Atlas.”

Bowmark gaped. There were hundreds of pages. Considering how long he took to read the first seven words, reading the rest of the book could take years.

Father continued. “I want you to find where the Southils live. Also, we need to find out if StoneGrove is marked in here. We need to know if we have been discovered.”

Bowmark shivered at the thought of the Southils invading their islands. He gripped his Giver’s Hand medallion. His throat squeaked and he coughed to cover the sound. As the king’s son and presumed he must not be weak. He must not, or the Southils might kill them all. He swallowed, and then sniffed. “I will, Father.”

He flipped a few pages to a drawing of people in outrigger canoes with rectangular sails rather than the triangle sails of the Sea Predators. He tried to remember to breathe as he sounded out each syllable. “The Hahn of the Longboats are a fractious people, seldom willing to trade. When they are willing, they trade dried fish, fresh fruit, and coconuts for steel needles and steel pots. Father, what does fractious mean?”

Father dipped his head and whispered, “Like RaiseHim.”

They exchanged smiles. Bowmark flipped to another page with an illustration of a creature with a long tail, holding its body in the position a bird does when walking. The word under the drawing was rumsha. “What kind of animal is this?”

Father studied the page and the words on the opposite page. “This is a non-human person. There are many kinds of non-human people in the wide world. The only non-human person I’ve ever met was a shlak. Someday I would like to see a varon seacastle floating on the ocean.”

Bowmark’s brain ignited. “Do all these people want to kill us?”

“So far as I know, only the Southils and their allies want to destroy us. All the other people of the world don’t care whether we are slaughtered or left to live.”

Bowmark ran his fingers along a sentence. “I will tell you everything I learn.”

“I am pleased.” Father gazed toward still far-off StoneShell. He shouted to the servants, “Furl the sail.”

Bowmark grinned. Father was pleased! As the band around Bowmark’s throat loosened, he vowed to himself that he would read as much as he needed to find what Father wanted to know. Bowmark would protect his people.

As Father’s orders were followed, all the outriggers in the entourage slowed to drift and bob on the surface of the ocean.

Father stood and raised his hands. “May Giver grant these innocent people rest- as He deals our enemies death and destruction.” He lowered his hands. They had not brought any priests with them. Who would say the Holy Words?

“Bury them,” Father said.

Silently, sailors picked up the bodies from the trampoline and slid them into the blue water. The bundles sank rapidly, the white sail wrappings disappearing in the deep. Then one sailor muttered, “The fish feed us, then we feed the fish.”

Father settled on the thwart, the board that served as brace and seat, next to Bowmark. He stared into the distance. No one said a word, holy or not, as servants reset the sail, and the canoe plowed through the sea toward Muntee Holm, an uninhabited island, to stay the night before heading for StoneShell. Bowmark had been looking forward to exploring the tiny uninhabited islet, but now he wanted to simply go home.

Buy the book here. [url=]https://www.amazon.com/Scarred-King-Exile-Tales-Talifar/dp/1942926030

by Josh Foreman

by Josh Foreman

by Josh Foreman

by Josh Foreman

Comments