Corpse Horn

We came across a battlefield then, three days old at most. Already the corpse horns had taken root, each crimson tube signalling a fresh widow.From their morbid life cycle to their alien appearance, these plants are looked upon with disgust across southern Cuyania.

Basic Information

Anatomy

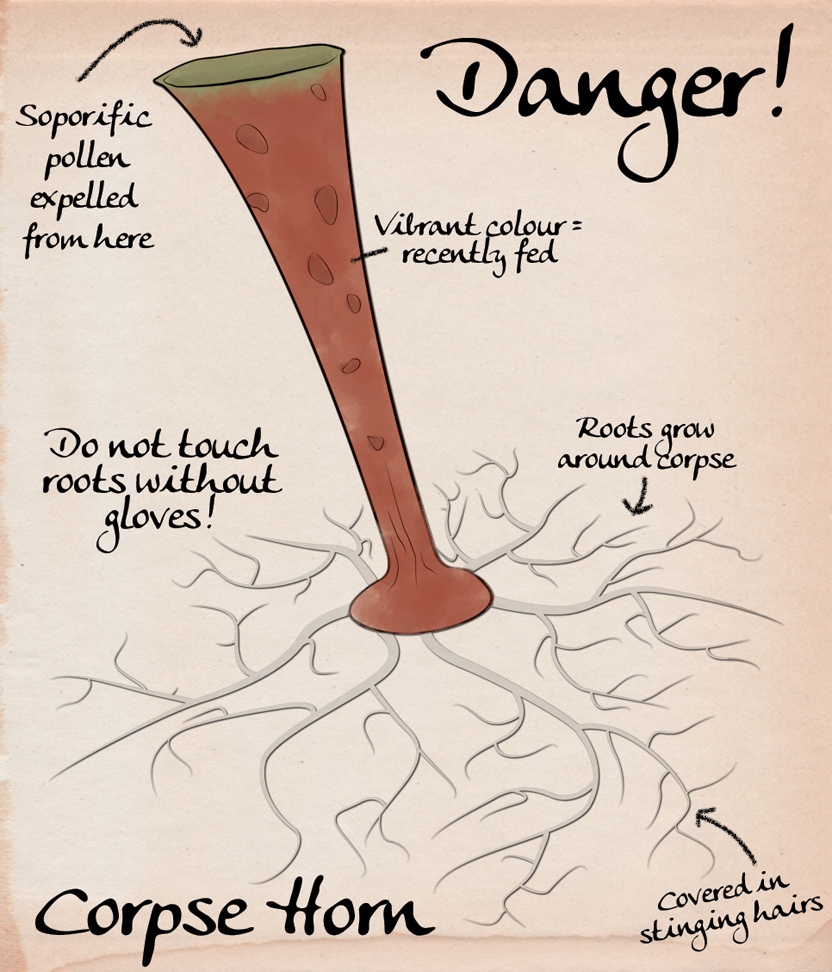

The corpse horn's most distinctive feature is its long tube that widens at the mouth, like an inverted cone. Each horn is about one to two feet long, and at its base, spreads into a network of roots.

The roots are exposed to the air, as the plant gains its sustenance from prey rather than soil nutrients The roots can grow quite long if they have ensnared a large animal. Each root is pale white and extends out from the base of the horn with thinner and thinner roots branch out.

Every inch of the root is covered in tiny stinging hairs that are hollow to suck up liquids. The hairs are serrated so that they pierce skin easily, but offer strong resistance to being pulled out. For this reason, gloves should always be worn when attempted to dislodge one.

The roots are exposed to the air, as the plant gains its sustenance from prey rather than soil nutrients The roots can grow quite long if they have ensnared a large animal. Each root is pale white and extends out from the base of the horn with thinner and thinner roots branch out.

Every inch of the root is covered in tiny stinging hairs that are hollow to suck up liquids. The hairs are serrated so that they pierce skin easily, but offer strong resistance to being pulled out. For this reason, gloves should always be worn when attempted to dislodge one.

Genetics and Reproduction

The plant reproduces by projecting seeds. The sides float on the wind and land on tall grass or bushes, and cling there with the fine hairs on the roots that are already sticking out of the seed. Each seed is about the size of a pinkie finger-nail, and 10 - 15 are released at a time. The seeds are shot out at the culmination of a meal, when the plant is at its peak health.

Eventually, a seed will be picked up by an animal brushing past it. The clinging hairs on the roots with stick to the animal's skin and allow it to take root. Soon, the roots break through and begin to dig into the animal. The roots suck blood from the animal like a tick, using its fluid and nutrients to grow.

The animal will not notice at first, but once they do, it will be too late to lick or scratch to get it off. Within a few hours, the animal will start to feel weak from the loss of blood and lie down to rest. This is where the next patch of corpse horns will grow. Once the first horn finishes its host meal, it will shoot out seeds of its own. Not every batch of seeds produces a new corpse horn; only about 25% of their seed projections result in a new patch taking root.

Every horn in a patch is genetically one plant. People commonly think of the horns as individuals, but they are all interwoven offshoots of the original.

Eventually, a seed will be picked up by an animal brushing past it. The clinging hairs on the roots with stick to the animal's skin and allow it to take root. Soon, the roots break through and begin to dig into the animal. The roots suck blood from the animal like a tick, using its fluid and nutrients to grow.

The animal will not notice at first, but once they do, it will be too late to lick or scratch to get it off. Within a few hours, the animal will start to feel weak from the loss of blood and lie down to rest. This is where the next patch of corpse horns will grow. Once the first horn finishes its host meal, it will shoot out seeds of its own. Not every batch of seeds produces a new corpse horn; only about 25% of their seed projections result in a new patch taking root.

Every horn in a patch is genetically one plant. People commonly think of the horns as individuals, but they are all interwoven offshoots of the original.

Corpse Gardens

A rare occurrence is when a patch takes root on a battlefield or other site of mass casualties. This happens when an animal infected by a seed arrives at a battlefield to scavenge the bodies. Even before the first horn is fully formed, roots reach out to the still-warm bodies lying around.

The roots spread rapidly through the field. As soon as one corpse is consumed, a horn shoots out seeds that land on another decaying corpse or scavenging animal. Every body gives rise to a fresh horn. Corpse horn patches on battlefields are some of the largest of their kind, and are a grisly sight to comrades returning to bury the dead.

In areas were corpse horns grow, some old soldiers have scars on their hands from the roots' clinging hairs after ripping them off of dead friends for a proper burial. Corpse gardens are usually seen as an ill omen, and potentially evidence that the gods do not condone the war.

The roots spread rapidly through the field. As soon as one corpse is consumed, a horn shoots out seeds that land on another decaying corpse or scavenging animal. Every body gives rise to a fresh horn. Corpse horn patches on battlefields are some of the largest of their kind, and are a grisly sight to comrades returning to bury the dead.

In areas were corpse horns grow, some old soldiers have scars on their hands from the roots' clinging hairs after ripping them off of dead friends for a proper burial. Corpse gardens are usually seen as an ill omen, and potentially evidence that the gods do not condone the war.

Corpse Horn First Aid

A patient infected by corpse horn roots is uncommon, but proper treatment must be learned. Most often, patients will be children who have not learned to not touch the roots bare-handed. Be sure to impress upon the child (and the parent) the importance of only touching the roots while wearing gloves.

It can be tempting to simply slip on leather gloves, firmly grasp the offending root, and pull. This is fast and effective, but leads to lasting scars. The roots do not come out easily, and will pull out skin when yanked. Depending on the extent of the roots and how long they have already had to consume blood, the resulting bleeding could kill a small patient.

The proper treatment is to douse the roots with a mixture of vinegar and salt. Liberally coat the roots with the mixture and then allow it to sit for about three or four hours. After this time, mixture will have caused the roots to shrivel and die, and they can then be removed easily.

Patients will likely still bleed from pin-hole sized puncture wounds, but these wounds will be much easier to bandage and deal with than what would result from ripping the roots out fresh.

Growth Rate & Stages

A corpse plant typically goes from seed-implantation to fully grown in about 3 days. In the beginning, it appears like skinny white worms on the skin of a dying animal. By the second day, the base of the horn is beginning to form and it starts reaching upward. On the third day, the roots continue to spread and the horn grows rapidly to its full size. The animal host generally dies on day two.

It will remain this size for the next few days, with the roots spreading and wrapping the host in increasing coverage of roots. When another animal is affected by the plant's soporific pollen, it will lie down in front of the plant, too woozy to leave. The roots of the first plant reach out to the new victim and take hold. The drugged animal cannot escape as the roots grow over it. The fresh food will result in a new horn growing.

After about a week, the original horn will begin to wilt and die from lack of food. On the other side of the patch, fresh horns are still growing on new meat. This causes patches to seem to slowly creep over the ground, leaving bones in their wake. Patches could continue to slowly creep onward indefinitely, but usually die out when they hit a body of water, cliff, or even a big log that prevents the roots from reaching new meat.

It will remain this size for the next few days, with the roots spreading and wrapping the host in increasing coverage of roots. When another animal is affected by the plant's soporific pollen, it will lie down in front of the plant, too woozy to leave. The roots of the first plant reach out to the new victim and take hold. The drugged animal cannot escape as the roots grow over it. The fresh food will result in a new horn growing.

After about a week, the original horn will begin to wilt and die from lack of food. On the other side of the patch, fresh horns are still growing on new meat. This causes patches to seem to slowly creep over the ground, leaving bones in their wake. Patches could continue to slowly creep onward indefinitely, but usually die out when they hit a body of water, cliff, or even a big log that prevents the roots from reaching new meat.

Dietary Needs and Habits

The corpse horn feeds on the blood and nutrients of warm-blooded animals. After it has sucked most of the blood from an animal, the horn is developed enough to begin to begin producing a digestive enzyme. This enzyme is fed through the roots and injected into the prey, causing it to internally liquefy. The plant sucks up this liquid as well until nothing but a dry husk is left.

Additional Information

Uses, Products & Exploitation

The pollen of the plant can be used a drug. In small doses, it can be used to reduce anxiety. Larger doses create a state of serene calmness, where the user feels no pain, no doubt, and no stress. In a safe environment, this state can be very relaxing.

Some groups from the jungle region use the pollen in spiritual rituals and believe the hypnotic trance is produces allows one to commune with the gods. Doctors also frequently drug their patients with it before performing surgery. In most organized nations, though, sale of it is strictly regulated due to its potential for abuse. An old story claims someone once used the pollen to create an army of hypnotized soldiers, and every now and then a case pops up of someone using it to manipulate a person into perpetual drugged servitude.

The pollen can either be inhaled or mixed into a drink. It tends to add sweetness to drinks, and is frequently mixed with a honey tea.

Some groups from the jungle region use the pollen in spiritual rituals and believe the hypnotic trance is produces allows one to commune with the gods. Doctors also frequently drug their patients with it before performing surgery. In most organized nations, though, sale of it is strictly regulated due to its potential for abuse. An old story claims someone once used the pollen to create an army of hypnotized soldiers, and every now and then a case pops up of someone using it to manipulate a person into perpetual drugged servitude.

The pollen can either be inhaled or mixed into a drink. It tends to add sweetness to drinks, and is frequently mixed with a honey tea.

Lifespan

6 months to a year

Average Height

1 - 2 feet

Body Tint, Colouring and Marking

The main horn is red on the outside and yellowish-green on the inside. The red colouring is produced from the iron absorbed out of blood, thus they are their most vibrant while sucking the blood from a host. Later in the digestive process, when they are mostly consuming liquefied muscle, the colour fades to a duller shade.

The roots are white, but can appear slightly blue while feeding for the same reason human veins appear blue when seen through pale flesh.

The roots are white, but can appear slightly blue while feeding for the same reason human veins appear blue when seen through pale flesh.