The pirate volor descended, Glory of Caesar in pursuit.

“Ease back on the throttle, don’t want to overspeed,” Felden said. “Eric, set brake force to ninety-five percent.”

Eric found the right dial, and twisted. His stomach lifted as the volor’s descent surged, its gravity brakes no longer fully countering Meridian’s pull.

“What sort of engines are in this, anyway?” Cobb asked.

“Magnetohydrodynamic drives,” Eric explained. “No moving parts, accelerates air with electricity—the solar collectors store it in superconducting coils.” He had an indicator for that, too, currently well in the green.

“There’s some nasty wind shear up ahead, I’m going to try luring them into it,” Felden said, then glanced to Prex. “We’ve got a few minutes, might want to get the cargo tied down.”

Prex whistled, several pirates hopped to it.

“Just skim the top…” Felden’s hands white-knuckled the wheel. “Then—thirty-degree down angle!”

Eric grabbed the Keeper control panel and felt Kadelius fall into his back. The volor buffeted.

Selva, who had gone aft and up, shouted back:

“No luck! They’re still on us!”

Felden grumbled and pulled up. They were almost level with the mountaintops, between them were valleys of scattered rocks.

“What about losing them in there?” Eric pointed to a winding cleft.

Zandra said, “No reason for them to follow. But if we take them someplace they think is safe…” Further starboard, a tall peak loomed above the others. “There’s a bunch of clear-air turbulence around that one.”

“Huh?” Now it was Eric’s turn to be confused.

“Boundary regions between air pockets moving at different speeds,” Felden explained. “Knocks you around if you fly into them unaware, and back on Ancient Terra they even destroyed oil-age jetliners.”

“We don’t want to kill anyone, though,” Zandra said.

“Hang on.” Felden leveled the craft. “Zandra, power!”

The volor surged and pitched upward. They flew into clear blue sky, well above the mountain’s height.

“They’re following!” Selva called back.

“Get ready, this one’s going to be rough. Decrease the throttle, let them catch up.” Felden turned to Eric. “I don’t want to dump too much power back into the coils, so when I say, turn the brakes down to fifty percent.”

“Fifty percent?” Eric’s eyes went wide. “We’ll fall out of the sky!”

Felden grinned. “That’s the idea.”

Avens really are insane, Eric decided. Though they probably thought the same thing about their genetic ancestors. A consequence of posthuman engineering—change a species’ appearance, and you change their minds too.

The Rogue’s Galley climbed at a near-forty-five-degree attitude, rushing up towards an unseen mass of moving air dead ahead. Felden was waiting until the last possible instant.

He said, “Eric...” Eric put his fingers to the gravity brake controls. “Now!”

Eric spun the dial half-around, Felden slammed the wheel forward and the volor plummeted downward. For a few seconds the cabin went into free-fall, Kadelius’ and Sir Wotoc’s eyes bulging in surprise. Weight returned, Eric stood and rushed aft to the great cabin.

Out its windows, the Glory of Caesar pitched down from its climb—too late. The Arztillan volor was clubbed from starboard by turbulence; crates and ropes flying from the deck, and with an audible snap a side-sail broke free and carried two gravity brakes with it. The crippled airship rolled dangerously, entering a spiral while the severed sail remained floating, power still in the superconducting coils of its gravity brakes. Its descent slowed, the crew attempting to level out, then it passed behind a mountain peak and Eric lost sight.

“Resume our course north,” Prex was saying when Eric returned.

As the sun set that evening, the Rogue’s Galley flew at sail, carried along by a northerly wind. Felden stood at the railing with a pair of binoculars, scanning out across the savanna-like plains below.

“Looking for something?” asked Eric.

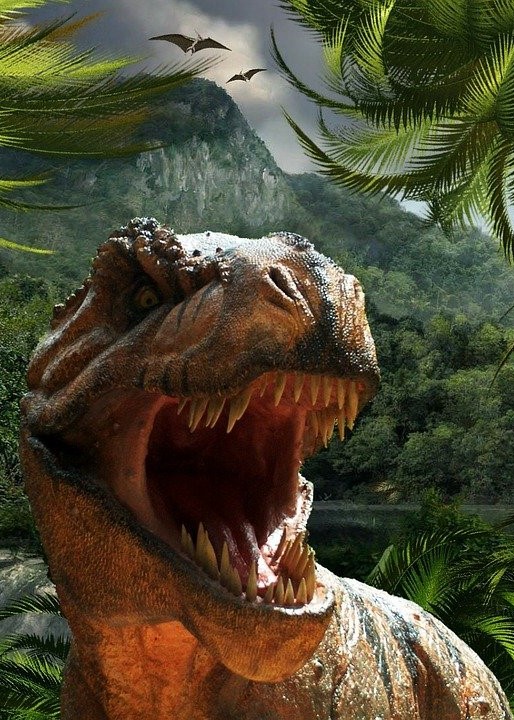

“Yeah, a T. rex.” He lowered the binoculars. “I want to see one for myself.”

“Careful what you wish for.”

Eric sighed as he walked over to where Temerin, Selva, and the others were sitting. After the past few months, he’d feel no great loss if he never saw another dinosaur again. Zandra handed him a ration bar as he sat down beside a crate, he nodded thanks. The avens had supplies salvaged from their crashed shuttle—food, computer tablets, stunners, medicine for the concussion that explosion gave him; a good amount but not near as much as they’d lost aboard the Argo.

Selva said, “I’ve been thinking, and I have a preliminary theory about the Keepers.”

“You said they were radical ecologists, right?” Cobb asked. “And this was their refuge?”

“In essence. The ideology I suspect the Keepers subscribed to goes all the way back to Terran industrialization, before starships and wormholes, two different views on human interaction with the environment and the ultimate fate of technological civilizations.

“The first started with Thomas Malthus and his theory that population growth led inexorably to mass starvation, later elaborated by William Vogt, Paul Ehrlich, Dennis Meadows, and others. Call them the Ecologists. They apply ecological principles to intelligent beings, chiefly the notion of overshoot and collapse. You see, when a population of animals—deer, say—is introduced to a new habitat fresh in resources, a common occurrence is a population boom fueled by a massive die-off when food supplies deplete.”

“And that’s what happened on Terra,” Zandra said. “They used too many resources, and their civilization collapsed. Petroleum depletion, global heating, that stuff.”

“I thought Terra fell because it grew corrupt,” Eric spoke up. “They had no frontier, so they turned inward and destroyed each other.”

Selva continued, “Regardless, Ecologist ideology is one of limits, where man must not grow too arrogant and foolish lest nature cut him down to size. Opposite them are the Economists, who tend to be much more optimistic about the future prospects of intelligent beings—people, unlike animals, do not only consume resources, but also create them. Oil was not a resource until industrialization, nor was uranium before the advent of atomic energy. For them, the crucial task is not to keep civilization within its ecological limits, but instead ensure society remains dynamic, capable of solving problems and innovating.”

“So then which one is it?” asked Cobb. “Is the truth somewhere in the middle?”

“No. In the end resources are limited and no recycling is perfect; all single-planet civilizations are doomed to collapse eventually. That’s why space colonization is necessary. People are smarter than the Ecologists give them credit for, but if they don’t take advantage of that they will indeed get a future of overshoot-and-collapse. It all goes back to a critical question the Existential Risks Directorate has: is human nature, or the natures of intelligent species in general, unsuited for advanced civilization? Do our inherited behaviors of greed, violence, et cetera, mean we’ll inevitably fall into self-destruction, or can we master our impulses and achieve lasting peace?”

“Can you?” Kadelius asked. He seemed to be following the conversation fairly well.

“Perhaps. Many scientists of ancient Terra would consider us a tremendous success—they thought the stars would only be reached slowly, if at all, and lived under a regime of state sovereignty which pathologically impeded international cooperation. But civilizations far more advanced than our own have collapsed despite possessing the capacity to secure their futures—the Enclavers and the Geometricians, for instance. However, we have managed to survive this far, whether by luck or something else.”

Zandra said, “Then there’s what our designer did: Make a new species without those atavistic flaws from caveman days. I dare say it’s worked—we’ve never fought a war with each other, our societies have low corruption and high equality, we’re scientific pioneers.”

“Humanity won’t want to be superseded,” Cobb replied.

“You may not have much choice. If humans can’t adapt, they’ll die out and people like us will be what’s left.”

Eric had nothing against avens, but he felt something would be lost if humans were replaced by beings like them.

“So the Keepers wanted to see if we could adapt?” Kadelius asked again.

Selva nodded. “I suspect they wished to see if human civilization could be made truly sustainable, able to endure indefinitely without collapse. Similar utopian projects have been tried many times in history, all have failed.”

“And the thing about that,” Temerin said, “is it’s poor saps like you who have to live with the consequences.”